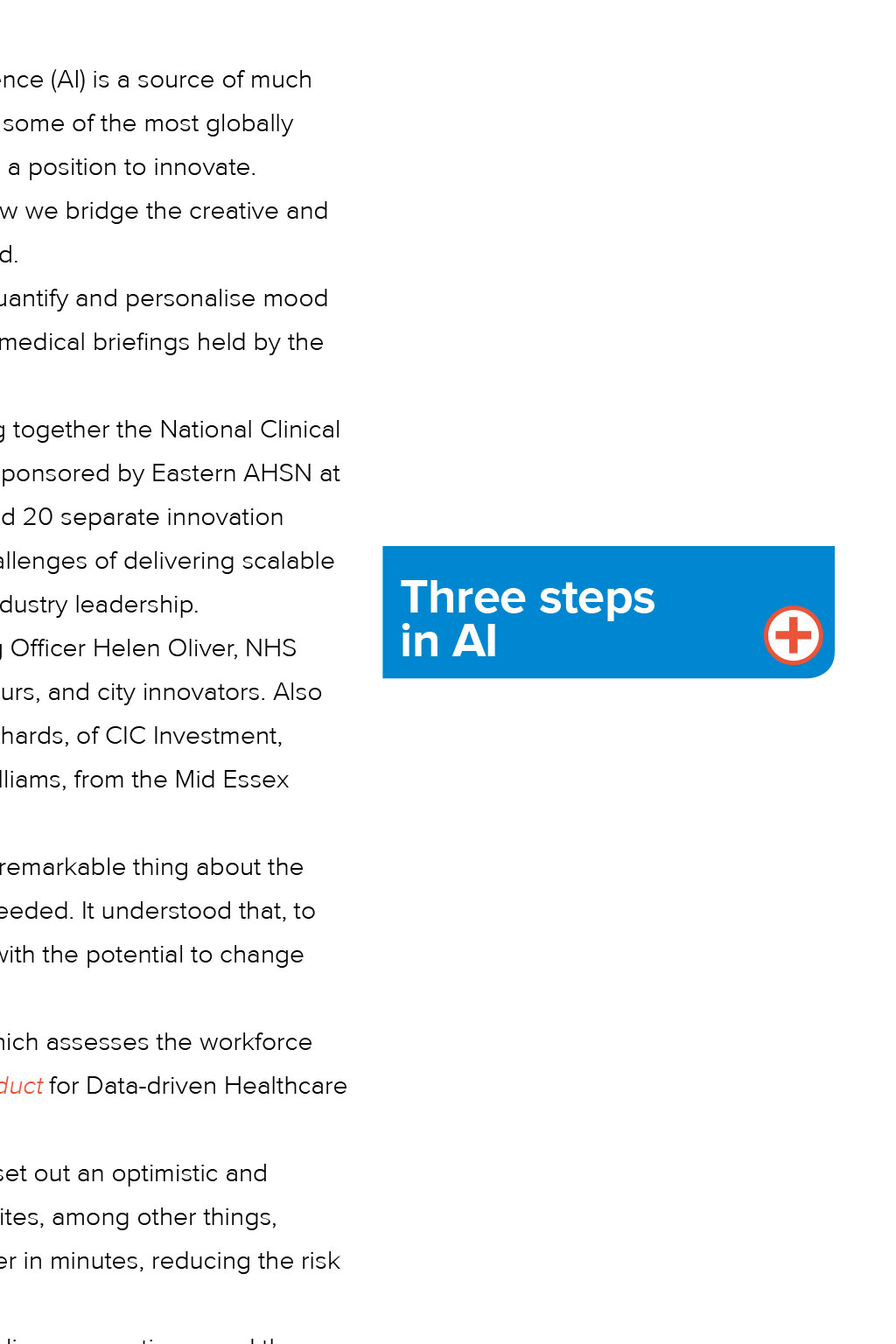

Opinion: Artificial intelligence AI’s not a dirty word Healthcare should be leading the way in employing artificial intelligence in an ethical way, says Dr Rozelle Kane “Public interest in AI and technology is a valuable catalyst for assessing our direction of travel, broadly and decisively. By creating a clear framework for the use of artificial intelligence as a tool, I believe we can build the bedrock for incredible progress” The technological capacity of artificial or algorithmic intelligence (AI) is a source of much excitement in the UK life sciences sector, which is home to some of the most globally significant research, as well as commercial organisations in a position to innovate. As a neuropsychologist and clinician, I’m interested in how we bridge the creative and ethical gap between these new tools and real societal need. For example, I’m working with researchers to test the capacity of AI to quantify and personalise mood disorders, and have been fortunate to contribute to events such as the AI medical briefings held by the Wellcome Trust UK and the American organisation AI-Med. In May this year, we began the first of a series of flagship events bringing together the National Clinical Entrepreneurs with local system leads for a lively panel debate. This was sponsored by Eastern AHSN at Downing College in Cambridge and attracted more than 120 attendees and 20 separate innovation demonstrations in the demo area. We discussed the opportunities and challenges of delivering scalable integrated care from the perspective of our healthcare system and from industry leadership. The expert panel that evening included Eastern AHSN’s Chief Operating Officer Helen Oliver, NHS England Lead for Innovation Professor Tony Young and clinical entrepreneurs, and city innovators. Also among the panellists were KPMG’s Lead for Data Rebecca Pope, Andy Richards, of CIC Investment, Dan Harding Jones, from Cambridge University Hospital, and Charlotte Williams, from the Mid Essex Hospitals Group. Despite there being differences in the approaches to the problems, the remarkable thing about the evening was that the panel was broadly in agreement on the next steps needed. It understood that, to scale truly integrated care, we require an openness to new technologies with the potential to change how we deliver services. NHS England recently launched two key reports – The Topol Review, which assesses the workforce challenges in expanding our technological interfaces, and A Code of Conduct for Data-driven Healthcare and Technology. Indra Joshi, digital health and AI clinical lead for NHS England, has also set out an optimistic and balanced view of how the NHS can be a leading force for ethical AI. She cites, among other things, radiological AI programmes that can identify women at risk of breast cancer in minutes, reducing the risk of their being missed or treatment delayed. Given the popularity of the technology, I’ve begun to think about the public conversation – and the discussions we might have as healthcare professionals – around a technology that could have a huge impact in the near future. Public interest in AI and technology generally is a valuable catalyst for assessing our direction of travel, broadly and decisively. By creating a clear framework for the use of AI as a tool, I believe we can build the bedrock for incredible progress. Equality of access is a central tenet of the NHS. If the massive ‘data lakes’ that are generated by it every day can be unified, the service could become an ethical leader in AI and healthcare. Like any great technological step, however, the technology alone will not define the legacy of AI – how it is applied will. So what is this technological expansion, and what does it mean for sectors such as the life sciences? Philosophical debate AI is not a new tool (see panel), but the exponential growth in computing power – and the drop in its cost – have been significant drivers of its progress. Its new capability challenges us in unusual ways, casting decision-makers and end users into philosophical debate. Despite some of the more alarming headlines, AI has no malicious intent. Once set in motion, however, we may not be able to peer into the trillions of steps that lead to an output. Many AI systems undergo unsupervised learning, so we are not following every step taken – and how we moderate this is still not clear. While this type of ‘black box’ play out may be a source of worry, we can protect against it by running parallel human decisions or creating appropriate checks. I am more concerned about our creative imagination – our ability, as sector experts, to grasp and share problem sets, and deliver efficiencies that can propagate across sectors. We are now seeing the early effects of mobile technologies on society – the social consequences of mobile screens drawing in retinas for hour upon hour. Such technology has changed the way we work, how we love and how we play – but what will be the impact on society of new smart algorithms? Should we draw our boundaries or learn to direct the progress? Such questions are particularly important in medicine; health data is among the most sensitive of individual data sets – but if we allow it to pass freely and on a grand scale, we might make powerful inferences for the greater good and efficiency of many. In my view, the issue is not whether we should do this, but how. The question is, who will be the gateway to such data – and how will we put in checks and balances? Three steps in AI About the author Communication paradox As a medical doctor working with AI, I have given a lot of thought to the distinction between individual and group benefit, security and clarity of purpose. Doctors are in a unique and privileged position; we’re trained to be the gatekeepers of the most private information you could share. People tell us – practical strangers – pieces of the tapestry of their world; things they might not tell anyone else; their worst day or most vulnerable side. This should never be transgressed. As doctors, however, we have the crucial knowledge of context and a duty to put our patients first – so we are well placed to advocate for the best uses of AI. In the UK, perhaps even in the west, we’ve not yet figured out how to disseminate medical data well. Given that there are now emerging healthcare branches in most of the biggest companies in the world – Alibaba and Amazon, and Google providing internal healthcare – the clock is ticking on our ability to share and develop the data we have in a powerful way. We need committed coalitions of healthcare leaders incentivised to lead public-private partnerships to solve their problems and create new knowledge for research and efficiency. And we need that now. Understandable biases might emerge as we develop AI for healthcare problems. Algorithmic model-based systems can be preferential to a given population, for example, producing a risk of forgetting the human individual or creating a ‘privileged first’ approach. This is no different from how we currently conduct research, with some populations under-represented – elderly patients in clinical trials, for example. The silver lining is that, with greater efficiency, it should be possible to bridge gaps in research more fully and quickly. Of course, population results are experientially very different from how we feel about our own lived experience: ‘It’s mine and no-one else’s’; ‘I’m me and not a predictable robot’; ‘My interpretation of this experience of living is unique and so are my decisions’. An AI doctor might create discordance and force fit individuals into predefined categories. This communication paradox is the most important ethical and application problem AI has, and is one of the reasons our conscious and compassionate use of AI – for efficiency, for example – is so key. We need to train our future leaders to expect to have more focus on individual, compassionate conversations, not less. It’s increasingly about what we don’t do any more: less time sifting through reams of text to synthesise it, or repeating multiple notes. Given the importance of big data sets for powerful conclusions in AI, the need for group thinking is understandable – but if we think about outcomes, we must remember the individual. We’ve got to get smart in communicating our conclusions to a diverse population. That, arguably, takes more energy and more effort than the conclusions themselves. AI’s not a dirty word Opinion: Artificial intelligence Healthcare should be leading the way in employing artificial intelligence in an ethical way, says Dr Rozelle Kane “Public interest in AI and technology is a valuable catalyst for assessing our direction of travel, broadly and decisively. By creating a clear framework for the use of artificial intelligence as a tool, I believe we can build the bedrock for incredible progress” The technological capacity of artificial or algorithmic intelligence (AI) is a source of much excitement in the UK life sciences sector, which is home to some of the most globally significant research, as well as commercial organisations in a position to innovate. As a neuropsychologist and clinician, I’m interested in how we bridge the creative and ethical gap between these new tools and real societal need. For example, I’m working with researchers to test the capacity of AI to quantify and personalise mood disorders, and have been fortunate to contribute to events such as the AI medical briefings held by the Wellcome Trust UK and the American organisation AI-Med. In May this year, we began the first of a series of flagship events bringing together the National Clinical Entrepreneurs with local system leads for a lively panel debate. This was sponsored by Eastern AHSN at Downing College in Cambridge and attracted more than 120 attendees and 20 separate innovation demonstrations in the demo area. We discussed the opportunities and challenges of delivering scalable integrated care from the perspective of our healthcare system and from industry leadership. The expert panel that evening included Eastern AHSN’s Chief Operating Officer Helen Oliver, NHS England Lead for Innovation Professor Tony Young and clinical entrepreneurs, and city innovators. Also among the panellists were KPMG’s Lead for Data Rebecca Pope, Andy Richards, of CIC Investment, Dan Harding Jones, from Cambridge University Hospital, and Charlotte Williams, from the Mid Essex Hospitals Group. Despite there being differences in the approaches to the problems, the remarkable thing about the evening was that the panel was broadly in agreement on the next steps needed. It understood that, to scale truly integrated care, we require an openness to new technologies with the potential to change how we deliver services. NHS England recently launched two key reports – The Topol Review, which assesses the workforce challenges in expanding our technological interfaces, and A Code of Conduct for Data-driven Healthcare and Technology. Indra Joshi, digital health and AI clinical lead for NHS England, has also set out an optimistic and balanced view of how the NHS can be a leading force for ethical AI. She cites, among other things, radiological AI programmes that can identify women at risk of breast cancer in minutes, reducing the risk of their being missed or treatment delayed. Given the popularity of the technology, I’ve begun to think about the public conversation – and the discussions we might have as healthcare professionals – around a technology that could have a huge impact in the near future. Public interest in AI and technology generally is a valuable catalyst for assessing our direction of travel, broadly and decisively. By creating a clear framework for the use of AI as a tool, I believe we can build the bedrock for incredible progress. Equality of access is a central tenet of the NHS. If the massive ‘data lakes’ that are generated by it every day can be unified, the service could become an ethical leader in AI and healthcare. Like any great technological step, however, the technology alone will not define the legacy of AI – how it is applied will. So what is this technological expansion, and what does it mean for sectors such as the life sciences? Philosophical debate AI is not a new tool (see panel), but the exponential growth in computing power – and the drop in its cost – have been significant drivers of its progress. Its new capability challenges us in unusual ways, casting decision-makers and end users into philosophical debate. Despite some of the more alarming headlines, AI has no malicious intent. Once set in motion, however, we may not be able to peer into the trillions of steps that lead to an output. Many AI systems undergo unsupervised learning, so we are not following every step taken – and how we moderate this is still not clear. While this type of ‘black box’ play out may be a source of worry, we can protect against it by running parallel human decisions or creating appropriate checks. I am more concerned about our creative imagination – our ability, as sector experts, to grasp and share problem sets, and deliver efficiencies that can propagate across sectors. We are now seeing the early effects of mobile technologies on society – the social consequences of mobile screens drawing in retinas for hour upon hour. Such technology has changed the way we work, how we love and how we play – but what will be the impact on society of new smart algorithms? Should we draw our boundaries or learn to direct the progress? Such questions are particularly important in medicine; health data is among the most sensitive of individual data sets – but if we allow it to pass freely and on a grand scale, we might make powerful inferences for the greater good and efficiency of many. In my view, the issue is not whether we should do this, but how. The question is, who will be the gateway to such data – and how will we put in checks and balances? Three steps in AI About the author Communication paradox As a medical doctor working with AI, I have given a lot of thought to the distinction between individual and group benefit, security and clarity of purpose. Doctors are in a unique and privileged position; we’re trained to be the gatekeepers of the most private information you could share. People tell us – practical strangers – pieces of the tapestry of their world; things they might not tell anyone else; their worst day or most vulnerable side. This should never be transgressed. As doctors, however, we have the crucial knowledge of context and a duty to put our patients first – so we are well placed to advocate for the best uses of AI. In the UK, perhaps even in the west, we’ve not yet figured out how to disseminate medical data well. Given that there are now emerging healthcare branches in most of the biggest companies in the world – Alibaba and Amazon, and Google providing internal healthcare – the clock is ticking on our ability to share and develop the data we have in a powerful way. We need committed coalitions of healthcare leaders incentivised to lead public-private partnerships to solve their problems and create new knowledge for research and efficiency. And we need that now. Understandable biases might emerge as we develop AI for healthcare problems. Algorithmic model-based systems can be preferential to a given population, for example, producing a risk of forgetting the human individual or creating a ‘privileged first’ approach. This is no different from how we currently conduct research, with some populations under-represented – elderly patients in clinical trials, for example. The silver lining is that, with greater efficiency, it should be possible to bridge gaps in research more fully and quickly. Of course, population results are experientially very different from how we feel about our own lived experience: ‘It’s mine and no-one else’s’; ‘I’m me and not a predictable robot’; ‘My interpretation of this experience of living is unique and so are my decisions’. An AI doctor might create discordance and force fit individuals into predefined categories. This communication paradox is the most important ethical and application problem AI has, and is one of the reasons our conscious and compassionate use of AI – for efficiency, for example – is so key. We need to train our future leaders to expect to have more focus on individual, compassionate conversations, not less. It’s increasingly about what we don’t do any more: less time sifting through reams of text to synthesise it, or repeating multiple notes. Given the importance of big data sets for powerful conclusions in AI, the need for group thinking is understandable – but if we think about outcomes, we must remember the individual. We’ve got to get smart in communicating our conclusions to a diverse population. That, arguably, takes more energy and more effort than the conclusions themselves. Three steps in AI 1950: Alan Turing discusses the possibility of reasoning machines in his paper Computing machinery and intelligence 1956: Computer scientist John McCarthy and cognitive scientist Marvin Minsky gather world- leading scientists at Dartmouth College, in the USA, to discuss the idea that reasoning machines were possible 2017: Google’s AlphaGo beats Chinese Go champion Kie Je About the author Dr Rozelle C Kane is a GP Registrar in Cambridge, Neuropsychologist and a National Clinical entrepreneur for the Department of Innovation NHS England.