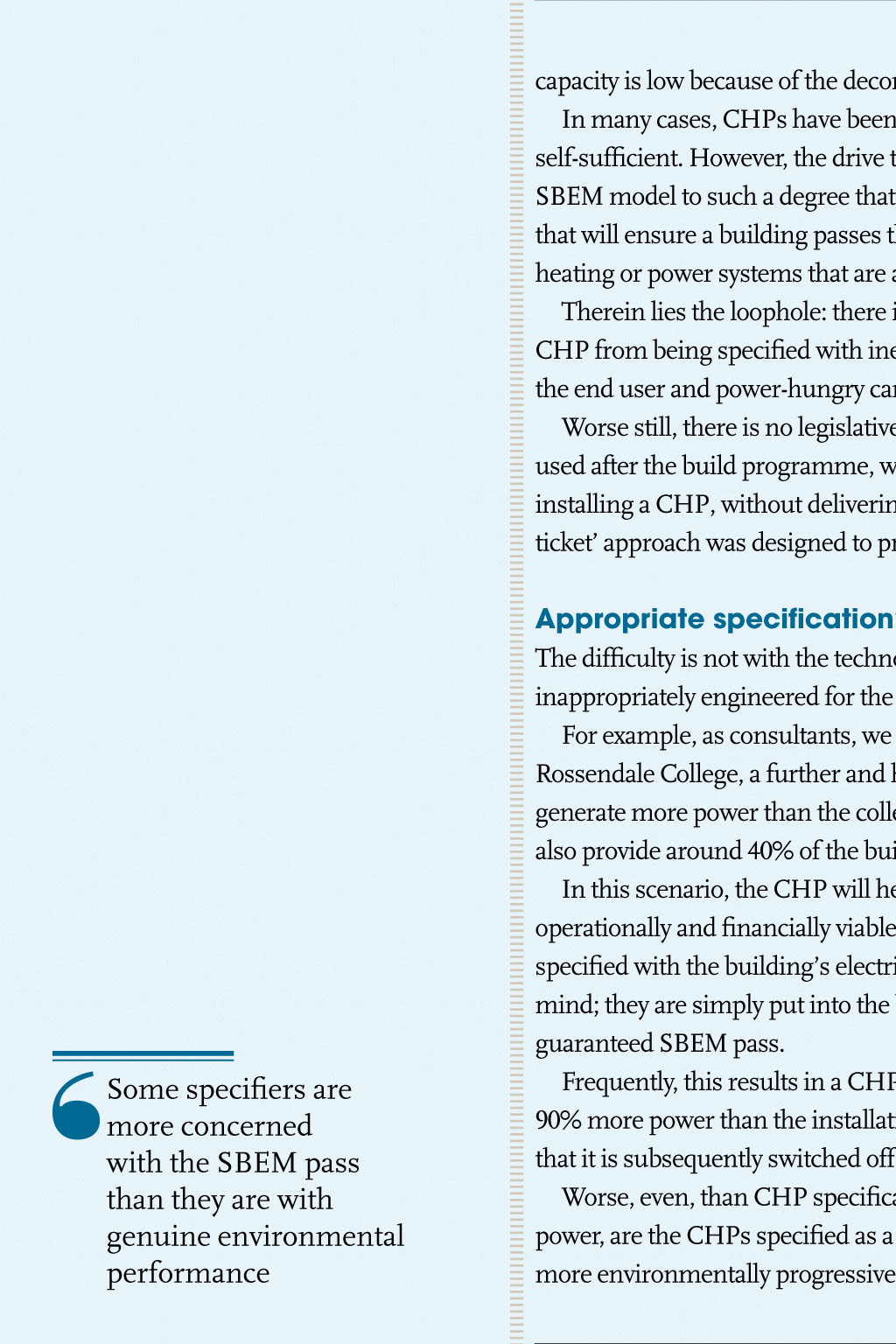

Opinion too much of a good thing CHP is often seen as a golden ticket that ensures a pass in SBEM. This loophole is driving an increase in specification at the expense of energy efficiency and operational costs, says Steve Hunt Steve Hunt FCIBSE is managing director at Steven A Hunt & Associates Web: www.stevenhunt.com @stevehuntassoc Twitter: The regulatory framework introduced to improve the sustainability of the built environment over the past 20 years has put a clear focus on energy efficiency. The Simplified Building Energy Model (SBEM) is at the heart of this, ensuring compliance with Part L of the Building Regulations, target emission rate (TER) requirements and EPC certification, using one, accountable methodology. It has been a very successful model; however, a major flaw relating to the specification of combined heat and power systems (CHPs) leaves the door open for inefficient buildings to pass straight through to compliance without accounting for their emissions. loophole Championed by the government as a solution to the heating and power needs of larger buildings, CHPs that have been correctly engineered to fit the requirements of an installation enable buildings to generate their own heat and power, taking pressure off the National Grid. Thats particularly beneficial at a time when the UKs generating capacity is low because of the decommissioning of coal-fired power stations. In many cases, CHPs have been correctly specified to make buildings more energy self-sufficient. However, the drive to encourage more CHPs has been built into the SBEM model to such a degree that they are often now perceived as a golden ticket one that will ensure a building passes the calculation automatically, regardless of any other heating or power systems that are also, or subsequently, specified. Therein lies the loophole: there is nothing in the SBEM calculation that prevents a CHP from being specified with inefficient electric heating systems, which are costly for the end user and power-hungry carbon emitters. Worse still, there is no legislative requirement for the CHP to be commissioned or used after the build programme, which enables specifiers to pass SBEM on the back of installing a CHP, without delivering any of the grid-capacity benefits that the golden ticket approach was designed to provide. Some specifiers are more concerned with the SBEM pass than they are with genuine environmental performance appropriate specification? The difficulty is not with the technology, but with the possibility of a CHP being inappropriately engineered for the needs of the building in question. For example, as consultants, we have recently specified a CHP for Accrington & Rossendale College, a further and higher education institution in Lancashire. It will not generate more power than the college needs, so it offers an efficient solution, which will also provide around 40% of the buildings heating requirements. In this scenario, the CHP will help the college to pass SBEM, while ensuring it is operationally and financially viable in the long term. Often, however, CHPs are not specified with the buildings electrical load or the occupiers operational needs in mind; they are simply put into the building, without good engineering reasons, as a guaranteed SBEM pass. Frequently, this results in a CHP that is too large for the building, producing up to 90% more power than the installation needs. It may, therefore, be so inefficient to run that it is subsequently switched off. Worse, even, than CHP specification that is badly engineered to deliver too much power, are the CHPs specified as a cynical ploy to avoid the additional build costs of a more environmentally progressive approach. Installing a CHP without any intention of running it avoids the capital costs of putting in the pipework infrastructure of a more traditional system, and allows the building to pass Building Regulations but it fails to deliver the promised energy efficiency. Unfortunately, some specifiers are more concerned with the SBEM pass than they are with genuine environmental performance and, as a result, I am aware of several projects where a CHP has been installed, but not commissioned. oversimplified As a profession, it is vital that the building services sector delivers the spirit of SBEM and doesnt simply comply with its requirements. CHP is an important technology but, if used inappropriately, it will not offer the benefits that it has the potential to provide. Accrington & Rossendale College has a small CHP, aligned to its energy requirements "