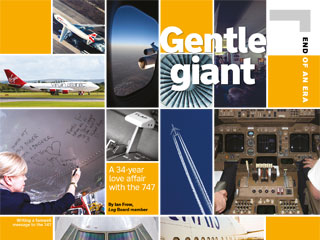

Gentle A 34-year love affair with the 747 By Ian Frow, Log Board member giant Writing a farewell message to the 747 The 2707 project possibly saved the 747 programme by making Boeing work out how to manufacture in titanium The problem was that, initially, the 747 undercarriage load- bearing structure was far too heavy, putting the project way overweight. Then someone remembered they already knew how to work titanium. Remarkably light and extraordinarily strong, it made all that high load-bearing gear structure possible. The engineers did a good job because it survived many of my more positive arrivals very well. Training plan Boeing were extremely hospitable – they lent us a car, and gave us a number of trips to various parts of its empire, including the first of the three great hangars at Everett where the first 747 wing was being built. The eight- acre hangar was just about complete. At one end was a machine straddling the wing with its chord vertical. On this machine sat a man controlling it or, more correctly, controlling the computer that controlled the machine. This behemoth was drilling and fixing the ‘fasteners’ between the wing structure and the top and bottom surfaces. The man’s main task seemed to be ensuring that, believe it or not, the paper tape controlling the computer did not tangle! I had a camera with me – no problems with security – but I took no pictures of that truly historic wing – stupid boy. Project saviour We did a couple of systems courses for Boeing to see how simple pilots might cope. Back at Boeing Field, we were allowed to crawl around the full-size wooden mock-up and see how it was even possible to climb up inside the massive fin. We were also proudly shown the wooden mock-up of the 2707, the Boeing supersonic project (eventually expensively abandoned in favour of the Lockheed design, also subsequently discarded). Later, I learnt that the 2707 project possibly saved the 747 programme by making Boeing work out how to manufacture in titanium. The 2707 was to be built using titanium, then an exotic material, very difficult to work. The story was that Boeing bought a mine in Queensland, set up a harbour there and another near Everett, together with a shipping line to move the titanium-bearing sand from Australia. A laboratory and smelter completed its successful titanium research. Back in the relaxed 70s, ground school was a leisurely nine or 10 weeks of chalk and talk. Following nine details in the simulator, we went to Prestwick for the aircraft base flying. My logbook says I flew in the seat for seven hours and 15 minutes, did 28 landings and, of course, spent many more hours on the aeroplane making coffee while everyone else flew the beauty. The training captains had a remarkably free hand and had us flying low- level circuits or setting the radio altimeter to 500ft or thereabouts, and flying down the Firth of Clyde ‘on the tone’. We also climbed to height to do high-Mach runs to demonstrate what a delightful plane it was at high- Mach numbers. How much did all that cost? By the end of training, we were confident in handling the 747 in all usual and unusual circumstances. Initially, the route options were limited. It was either New York with a Bermuda shuttle or to Nairobi with a slip, followed next day by a Johannesburg slip and back again next day to Nairobi. The northbound flight out of Nairobi at 5,500ft stretched the abilities of the early 747 to its limits. On all too many take-offs, the end of the runway seemed awfully close and often it was necessary to make a fuel tech stop in Athens. The 747 was truly groundbreaking, and cheap long-haul flying – until recently, available to all – began with the construction of that wing. The economics of the 70s meant load factors were often poor and, as the network expanded, it was not unusual to fly to Chicago with only 20 or so passengers on board. But because of the freight-carrying capacity of the 747 (and a good contract), those flights still broke even or even made money. The architect Norman Foster described the 747 as “the greatest building ever flown” Interesting failures In 1976, I was one of the fortunate long-term right-hand seaters to make the transition to the left-hand seat, still on the 747. Engines were not then as reliable as the ETOPs-cleared varieties now in use, and I had one or two interesting failures. On one occasion, the back end of the engine spectacularly came apart approaching Istanbul en route to LHR. Until we slowed down, the aircraft was vibrating so badly that the instruments were difficult to read, so I chickened out and diverted to Istanbul. Many passengers were bound for the pre-wedding festivities of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. They were not best pleased to spend a long day marooned on board at that marvellous city’s airport. The high-bypass engines demonstrated their sturdiness on an earlier Nairobi take-off. I was the handling pilot in the right-hand seat when, just before the rotate call, a flock of large-wingspan kites, common to Africa, decided to lift off the runway, too. They disappeared from my sightline behind the captain and it seemed an age before there were two substantial bangs as both port engines surged. Continuing with the rotate, I found that full right rudder and aileron were not quite enough to stop the inexorable enthusiasm of the aircraft to fly upside down. Fortunately, the outboard engine almost immediately recovered from its surge, and started giving power followed 10 seconds later by its inboard colleague. We were blessed with the presence of a flight engineer who went into his engine health check routine as we pilots shakily continued our departure. Having found no obvious problems, the decision was made to continue to Johannesburg where the engineering back up was substantial. In Jo’burg, both engines were examined and borescoped, but no damage was found. However, they did find one white feather! Gender balance In the late 80s, British Airways had at last recruited female pilots. By then, I was a training captain and supervised Lynn Barton, one of the first three, on her first and third 747 passenger-carrying trips. Her appearance on the flight deck caused a certain amount of interest, especially among the female cabin crew. She, and all her female colleagues that I subsequently trained on the 747 over the next 10 years, had little difficulty flying the monster, proving brute strength was not required. Famous faces The flight deck of 747 is relatively roomy, which meant that – in pre-locked door days – it was possible to entertain all sorts of interesting people. Flying into Johannesburg in 1992, Nelson Mandela – before he became president of South Africa – joined us for more than an hour and stayed for the landing. He was interesting, charismatic, and enthusiastic about the future prospects for all the people of his country. Then there was the famous opera singer who sat in for the arrival into New York and remarked as she left the flight deck: “Well, I’ve seen you lot at work, now you can come and hear me screech my head off!” The only royals I flew were the Princess of Wales and her two princes. The boys came up for the departure from San Francisco but, after they had left us at the top of climb, the northern part of America produced a remarkable selection of wicked cumulonimbus for the next three hours. By the time we had finished slaloming around them, with the seat belt signs on, the royal party was asleep and stayed that way until the descent into London. Thus, that flight deck crew and I have the unusual record of having spent 10 hours sitting some 20 feet ahead of one of the world’s most famous women of her time, without ever meeting her! Having first flown the 747 in spring 1972, I stayed on it, with pauses between airlines, until spring 2002, some 30 years. Including the Seattle experience, plus a few other involvements before she came into service, I could claim that the Queen of the Skies was a part of my flying career, and also a love affair for 34 years. During those years, I was also involved with BALPA’s Concorde evaluation and had the pleasure of some handling time on that unique aircraft. It was a great privilege to have flown the fastest commercial aircraft, used mainly by the rich and famous. But perhaps it was even better to spend many years flying what the architect Norman Foster has described as “the greatest building ever flown” – the aircraft that really opened up the world to all. n late 1967, I was rostered as part of a crew to collect a new 707 from Boeing in Seattle. It should have taken five days, but took infinitely longer. The one duff engine causing the delay was eventually replaced by BOAC’s spare engine in San Francisco. Between SFO and SEA, this engine was dropped, luckily with only minor damage. By the time Boeing engineers, Boeing lawyers, the insurers and BOAC and its lawyers had sorted out the issues, it was three weeks before we flew G-ATWV home. END OF AN ERA