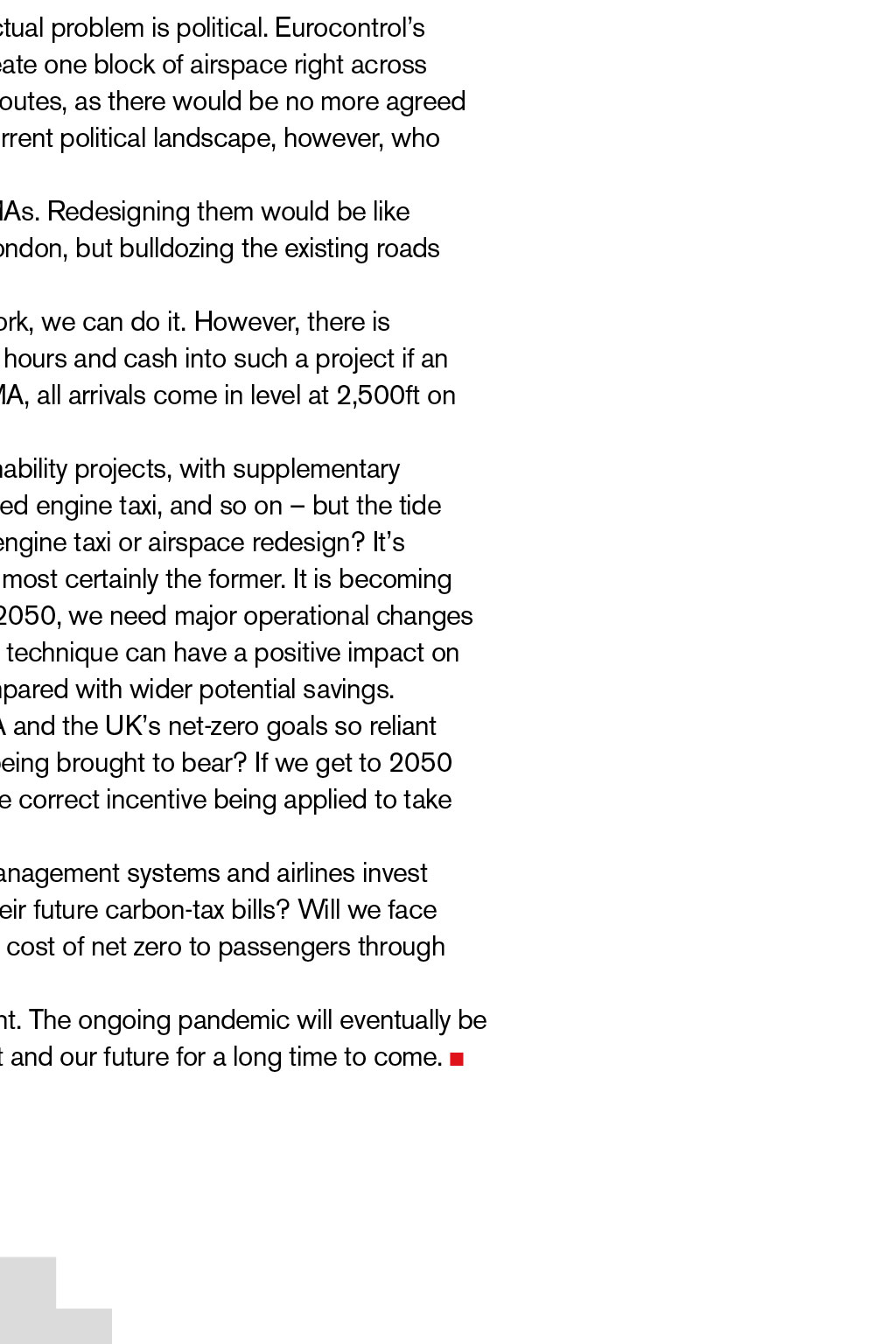

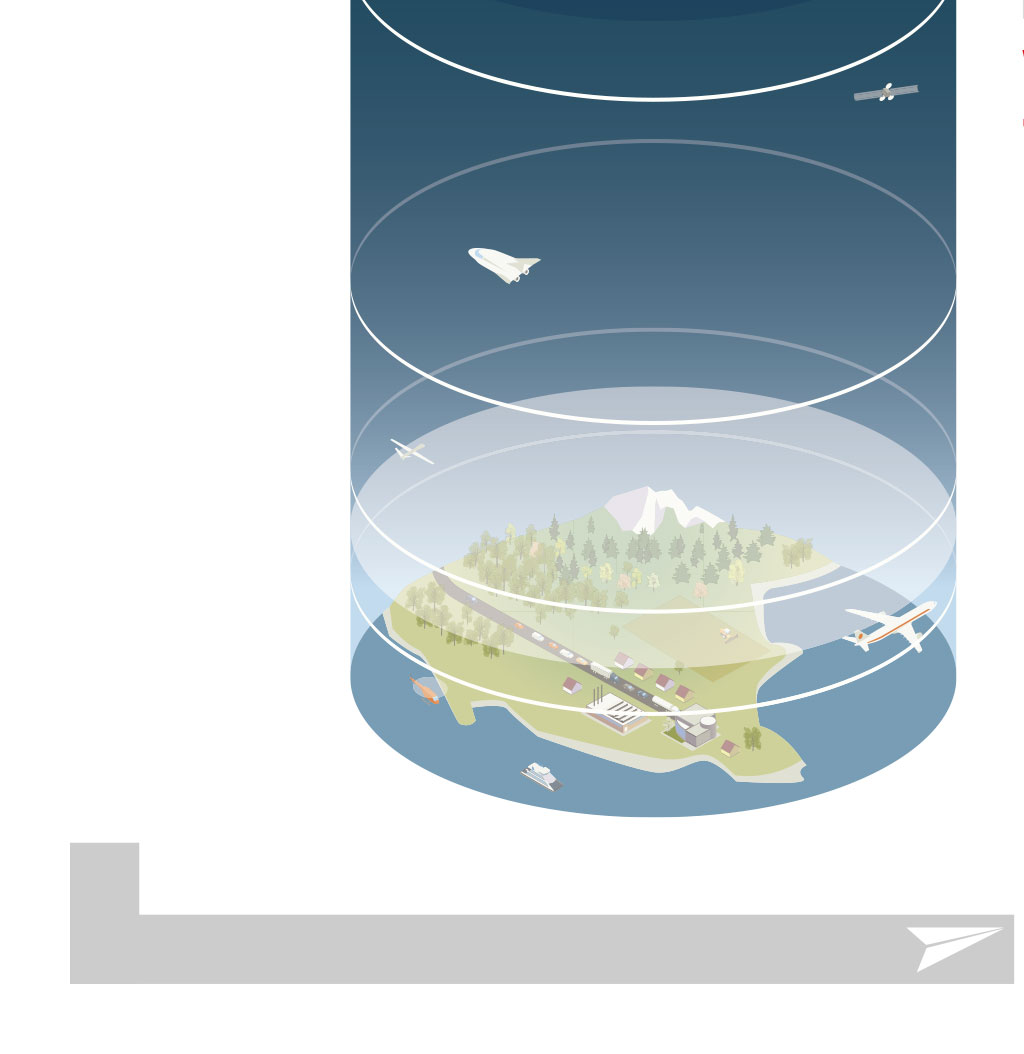

Time is running out for aviation to make the changes necessary to become net zero by 2050 – but can it be done? Emissions impossible? By First Officer Adam Crehan-Clark, BALPA member ack in February, we were living in innocent bliss. There were rumblings about some virus in the Far East, but, for the most part, it seemed like a normal February in the UK: a bit wet, a bit dreary, and largely unremarkable. Quite remarkably during this month, however, a group of UK airlines and aviation companies committed to ‘net zero’ carbon emissions by 2050. The UK Sustainable Aviation Coalition launched its roadmap to net zero on 4th February, an event soon overshadowed by the COVID-19 pandemic. As we return to a ‘new normal’, however, it is time to take a look at this net-zero 2050 plan and what it means for us in aviation. Although aviation is a minority source of the UK’s total greenhouse gas emissions, we are one of the highest-profile, largely because of our high energy use per mile, which makes aviation one of the least efficient methods of transport. The reducing cost of entry to aviation has also allowed more people to enjoy the benefits of air travel, increasing our share of emissions dramatically. No-one can deny we need to take action. The big question is: what does net zero even mean? Achieving balance It means there is a balance between the greenhouse gases put into the atmosphere and the amount removed. This can be achieved by reducing emissions or improving removal rates via forests, oceans or artificial carbon-capture techniques. Net zero is different from gross zero, where we produce zero excess greenhouse gases. This is the ultimate goal, but is neither attainable nor practical at present. If we reach a net-zero point, however, this should buy us time to innovate our way towards a gross-zero global community. The net-zero plan (bear in mind this was all pre-lockdown) estimated that passenger numbers in the UK would increase by 70% from 2019 to 2050. This compounds the problem, because not only do we have to get our current emissions to net zero, but we also need to get our future demand to net zero. As such, a herculean effort is required to reach this target. The main initiatives being proposed, and their 2050 emission savings, are: 1. Market-based policy measures (a CO2 emission tax) = an offset of 25.8 million tonnes of carbon dioxide (MtCO2) 2. Improvements in aircraft and engine efficiency = 23.5 MtCO2 3. Sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) = 14.4 MtCO2 4. The tax in item 1 reducing passenger demand by raising the average ticket price = 4.3 MtCO2 5. Airspace modernisation = 3.8 MtCO2 The fear of the UK Sustainable Aviation Coalition is that aviation can’t innovate in time. Green technology solutions exist in almost all other fields, but the physics around biofuels and electric-powered commercial aircraft prevent us from changing the aviation status quo for the foreseeable future – especially if funding in these areas isn’t vastly increased. Also, the average lifespan of a commercial jet is 30 years, so, if we are to reach our net-zero goal via new aircraft types, we need to enter them into service now. While our latest Neo, Max and composite aircraft are great steps forward, they don’t go far enough by themselves. As a solution, in 2016 the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) adopted the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA). This is a global scheme to encourage biofuel development and introduce a structured, fixed carbon-emission tax (called ‘carbon pricing’). All countries introduce the CO2 emission tax at the same rate and time, keeping a level playing field on ticket prices. The expectation is that carbon pricing will rise steadily from $10 in 2021 (CORSIA target) to around £221 per tonne of CO2 by 2050 (UK net-zero target). For scale, if we applied that higher carbon price to 2019, it would have generated $210bn globally for offsetting carbon emissions – more than a quarter of the entire aviation industry’s global revenues ($810bn in 2019). In the UK, we expect this tax to offset 25.8 million tonnes of CO2 by 2050. The money raised would go to potential eco projects, including wind and solar energy, clean-cook stoves, methane capture, forestry and other emissions-reducing schemes. It will also help prevent deforestation and fund reforestation. However, this money cannot be used to fund innovation in aviation efficiency. The $210bn per year would vastly accelerate electric aircraft research but, under the net-zero/CORSIA plan, it must go towards offsetting carbon emissions instead – potentially pushing us further away from the real goal of gross zero. Originally, the idea was to take 2019 and 2020 data to baseline the carbon output, but the current 2020 emissions are so low that it would skew the baseline away from a potentially realistic target. So, the proposal now is just to take 2019 as a baseline. If we are to reach our net-zero goals via new aircraft types, we need to enter them into service now Fuelling the debate Another ICAO measure to cut the sector’s environmental impact is to encourage alternative fuels. We don’t yet have a standard of alternative fuel technology; current eligible concepts range from high-efficiency fossil fuels to bio-fuels from livestock. Known as Sustainable Aviation Fuels (SAFs), the two most promising technologies are ethanol-based fuels derived from the run-off of heavy-metal plants (for example, steel mills) and the processing of livestock waste into a biofuel. Virgin Atlantic flew Orlando to Gatwick on a flight powered entirely by a SAF in 2018. In the future, however, it’s more reasonable to expect 50/50 mixes of SAF and kerosene than 100% SAF flights. Efforts are also under way to make sure that CO2 emissions aren’t just passed upstream. Livestock are notorious CO2 emitters; the agricultural industry contributes about 10% of the total greenhouse gas output globally. As with other fuel sources, such as hydrogen, current processes of generating the fuel have the potential to negate the savings, usually because of economies of scale. Building a new SAF jet- fuel plant can produce a lot of CO2 emissions and may output a small amount of fuel, but we can produce kerosene at great volumes and improve on existing techniques. This makes the ratio of fuel-burn to fuel-creation emissions much lower. One of the more frustrating obstacles to net zero is airspace. Anyone who’s spent time in the London TMA will understand the situation of stacked and crisscrossing arrivals laid over and under departures routes. Pilots are often left hoping for a quick breakaway climb to get over inbound traffic, which sometimes doesn’t happen until well outside of the London area. The frustration is that we have the technology to rewrite the airspace. With performance-based navigation ubiquitous across most of the latest generation of aircraft, complex routes relying on NDB or VOR tracks seem outdated, especially when they’re flown with a GPS overlay! A plethora of aircraft could, realistically, today – at thrust-reduction altitude (obstacles permitting) – turn on a direct heading to the final fix at their destination. This direct-to approach would also help our air traffic management systems judge arrival times more accurately. Estimating fuel burn, arrival times and delays would become easier, and the knock-on effect would be a reduction in the dreaded mid- summer, two-hour-plus slot delay. This would also affect APU fuel usage, and mean continuous descent approaches could be performed almost all the time with far greater ‘track miles to go’ accuracy. Political issues So, technology is not a problem; the first actual problem is political. Eurocontrol’s Single European Sky project is trying to create one block of airspace right across Europe, which would allow for direct-to-fix routes, as there would be no more agreed handover points between sectors. In the current political landscape, however, who knows if this vision will be implemented? Another problem is the complexity of TMAs. Redesigning them would be like planning a 12-lane superhighway across London, but bulldozing the existing roads while drivers were still using them. With careful planning and meticulous work, we can do it. However, there is reluctance to pile the huge amount of work hours and cash into such a project if an hour away, in a neighbouring capital city TMA, all arrivals come in level at 2,500ft on excessive tracks. Pilots often shoulder the brunt of sustainability projects, with supplementary SOPs around reduced flap landings, reduced engine taxi, and so on – but the tide is turning. What saves more fuel: reduced engine taxi or airspace redesign? It’s probably the latter – but which is easier? Almost certainly the former. It is becoming clearer, however, that to get to net zero by 2050, we need major operational changes – and the time for these is now. Flight-crew technique can have a positive impact on emissions, but it is a drop in the ocean compared with wider potential savings. All this begs the question: with CORSIA and the UK’s net-zero goals so reliant on carbon pricing, is the correct pressure being brought to bear? If we get to 2050 and just pay the difference to net zero, is the correct incentive being applied to take climate change seriously? Will airframe manufacturers, air traffic management systems and airlines invest in innovation, or will they invest to pay off their future carbon-tax bills? Will we face a situation where airlines pass on the entire cost of net zero to passengers through higher fares? Having the conversation now is important. The ongoing pandemic will eventually be over, but climate change will be our present and our future for a long time to come. What saves more fuel: reduced engine taxi or airspace redesign? Probably the latter – but which is easier? Left: An illustrated diagram shows the layers of Earth’s atmosphere: the exosphere, thermosphere, mesosphere, stratosphere and troposphere, and includes a representation of the ozone layer. Layers are delineated at roughly accurate altitudes CARBON EMISSIONS Emissions CARBON EMISSIONS Emissions impossible? CARBON EMISSIONS Time is running out for aviation to make the changes necessary to become net zero by 2050 – but can it be done? impossible? Emissions CARBON EMISSIONS Time is running out for aviation to make the changes necessary to become net zero by 2050 – but can it be done? impossible? Emissions By First Officer Adam Crehan-Clark, BALPA member CARBON EMISSIONS