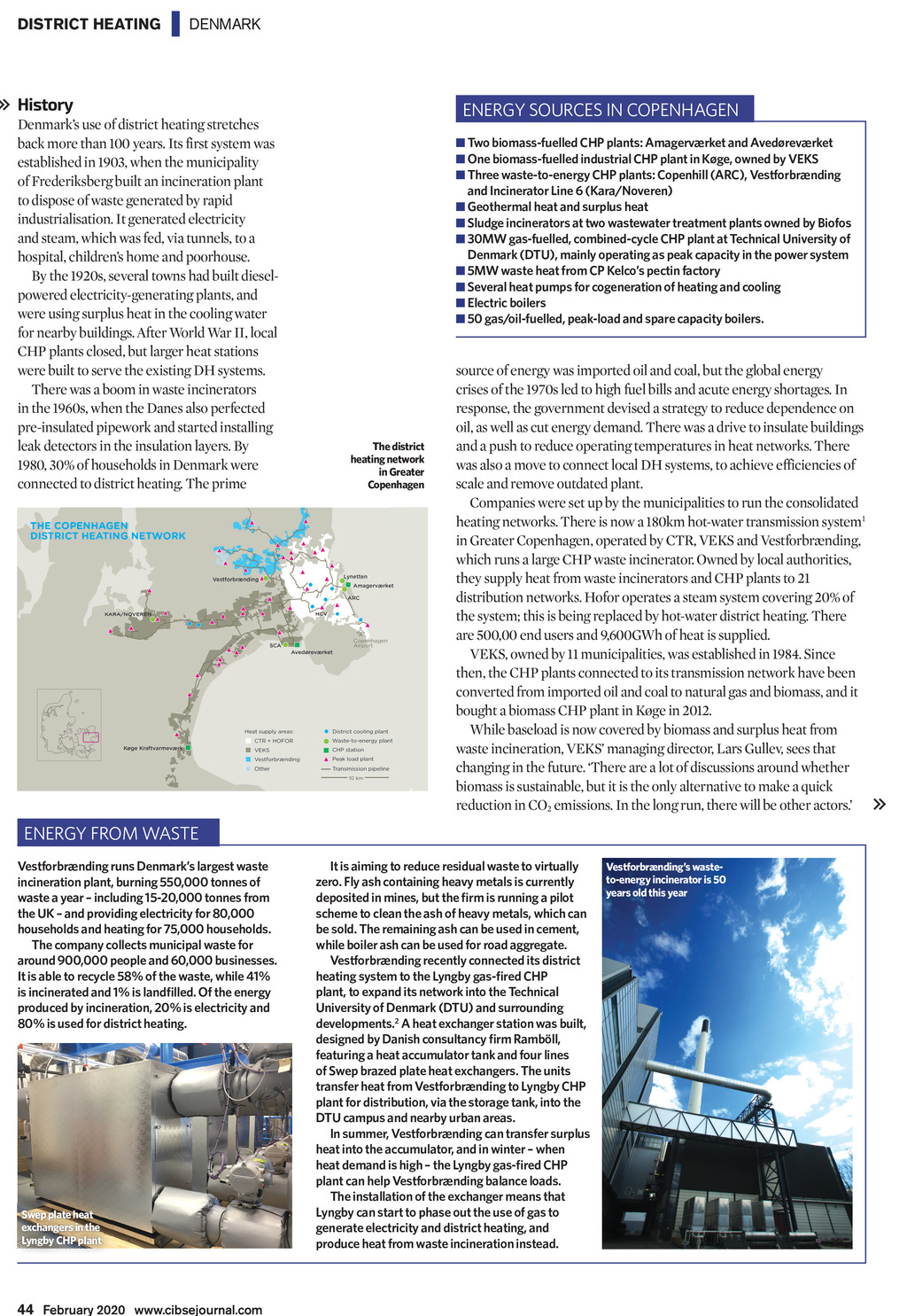

DISTRICT HEATING | DENMARK History Denmarks use of district heating stretches back more than 100 years. Its first system was established in 1903, when the municipality of Frederiksberg built an incineration plant to dispose of waste generated by rapid industrialisation. It generated electricity and steam, which was fed, via tunnels, to a hospital, childrens home and poorhouse. By the 1920s, several towns had built dieselpowered electricity-generating plants, and were using surplus heat in the cooling water for nearby buildings. After World War II, local CHP plants closed, but larger heat stations were built to serve the existing DH systems. There was a boom in waste incinerators in the 1960s, when the Danes also perfected pre-insulated pipework and started installing leak detectors in the insulation layers. By 1980, 30% of households in Denmark were connected to district heating. The prime ENERGY SOURCES IN COPENHAGEN Two biomass-fuelled CHP plants: Amagervrket and Avedrevrket One biomass-fuelled industrial CHP plant in Kge, owned by VEKS Three waste-to-energy CHP plants: Copenhill (ARC), Vestforbrnding and Incinerator Line 6 (Kara/Noveren) Geothermal heat and surplus heat Sludge incinerators at two wastewater treatment plants owned by Biofos 30MW gas-fuelled, combined-cycle CHP plant at Technical University of Denmark (DTU), mainly operating as peak capacity in the power system 5MW waste heat from CP Kelcos pectin factory Several heat pumps for cogeneration of heating and cooling Electric boilers 50 gas/oil-fuelled, peak-load and spare capacity boilers. The district heating network in Greater Copenhagen source of energy was imported oil and coal, but the global energy crises of the 1970s led to high fuel bills and acute energy shortages. In response, the government devised a strategy to reduce dependence on oil, as well as cut energy demand. There was a drive to insulate buildings and a push to reduce operating temperatures in heat networks. There was also a move to connect local DH systems, to achieve efficiencies of scale and remove outdated plant. Companies were set up by the municipalities to run the consolidated heating networks. There is now a 180km hot-water transmission system1 in Greater Copenhagen, operated by CTR, VEKS and Vestforbrnding, which runs a large CHP waste incinerator. Owned by local authorities, they supply heat from waste incinerators and CHP plants to 21 distribution networks. Hofor operates a steam system covering 20% of the system; this is being replaced by hot-water district heating. There are 500,00 end users and 9,600GWh of heat is supplied. VEKS, owned by 11 municipalities, was established in 1984. Since then, the CHP plants connected to its transmission network have been converted from imported oil and coal to natural gas and biomass, and it bought a biomass CHP plant in Kge in 2012. While baseload is now covered by biomass and surplus heat from waste incineration, VEKS managing director, Lars Gullev, sees that changing in the future. There are a lot of discussions around whether biomass is sustainable, but it is the only alternative to make a quick reduction in CO2 emissions. In the long run, there will be other actors. ENERGY FROM WASTE Vestforbrnding runs Denmarks largest waste incineration plant, burning 550,000 tonnes of waste a year including 15-20,000 tonnes from the UK and providing electricity for 80,000 households and heating for 75,000 households. The company collects municipal waste for around 900,000 people and 60,000 businesses. It is able to recycle 58% of the waste, while 41% is incinerated and 1% is landlled. Of the energy produced by incineration, 20% is electricity and 80% is used for district heating. Swep plate heat exchangers in the Lyngby CHP plant 44 February 2020 www.cibsejournal.com It is aiming to reduce residual waste to virtually zero. Fly ash containing heavy metals is currently deposited in mines, but the rm is running a pilot scheme to clean the ash of heavy metals, which can be sold. The remaining ash can be used in cement, while boiler ash can be used for road aggregate. Vestforbrnding recently connected its district heating system to the Lyngby gas-red CHP plant, to expand its network into the Technical University of Denmark (DTU) and surrounding developments.2 A heat exchanger station was built, designed by Danish consultancy rm Rambll, featuring a heat accumulator tank and four lines of Swep brazed plate heat exchangers. The units transfer heat from Vestforbrnding to Lyngby CHP plant for distribution, via the storage tank, into the DTU campus and nearby urban areas. In summer, Vestforbrnding can transfer surplus heat into the accumulator, and in winter when heat demand is high the Lyngby gas-red CHP plant can help Vestforbrnding balance loads. The installation of the exchanger means that Lyngby can start to phase out the use of gas to generate electricity and district heating, and produce heat from waste incineration instead. Vestforbrndings wasteto-energy incinerator is 50 years old this year