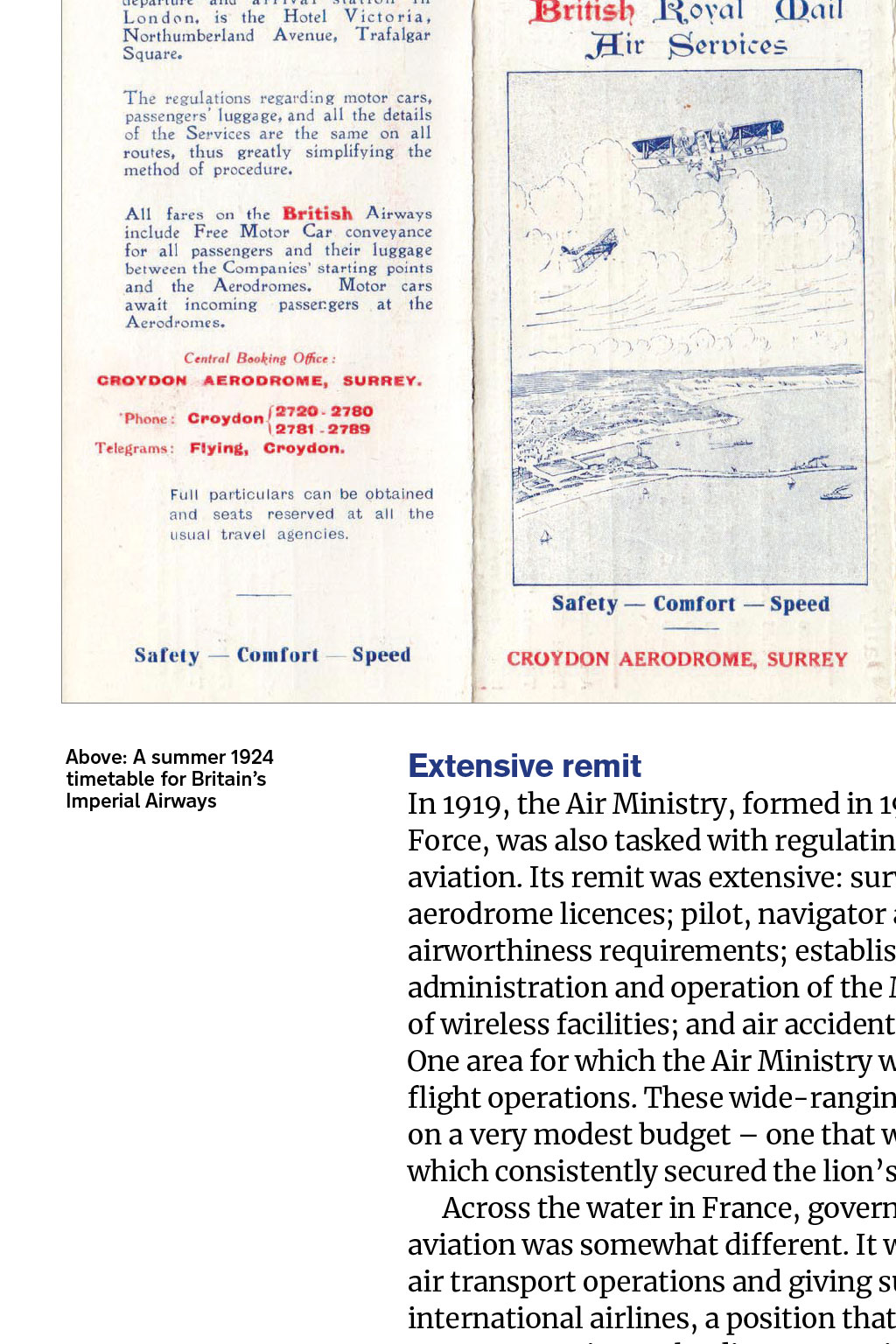

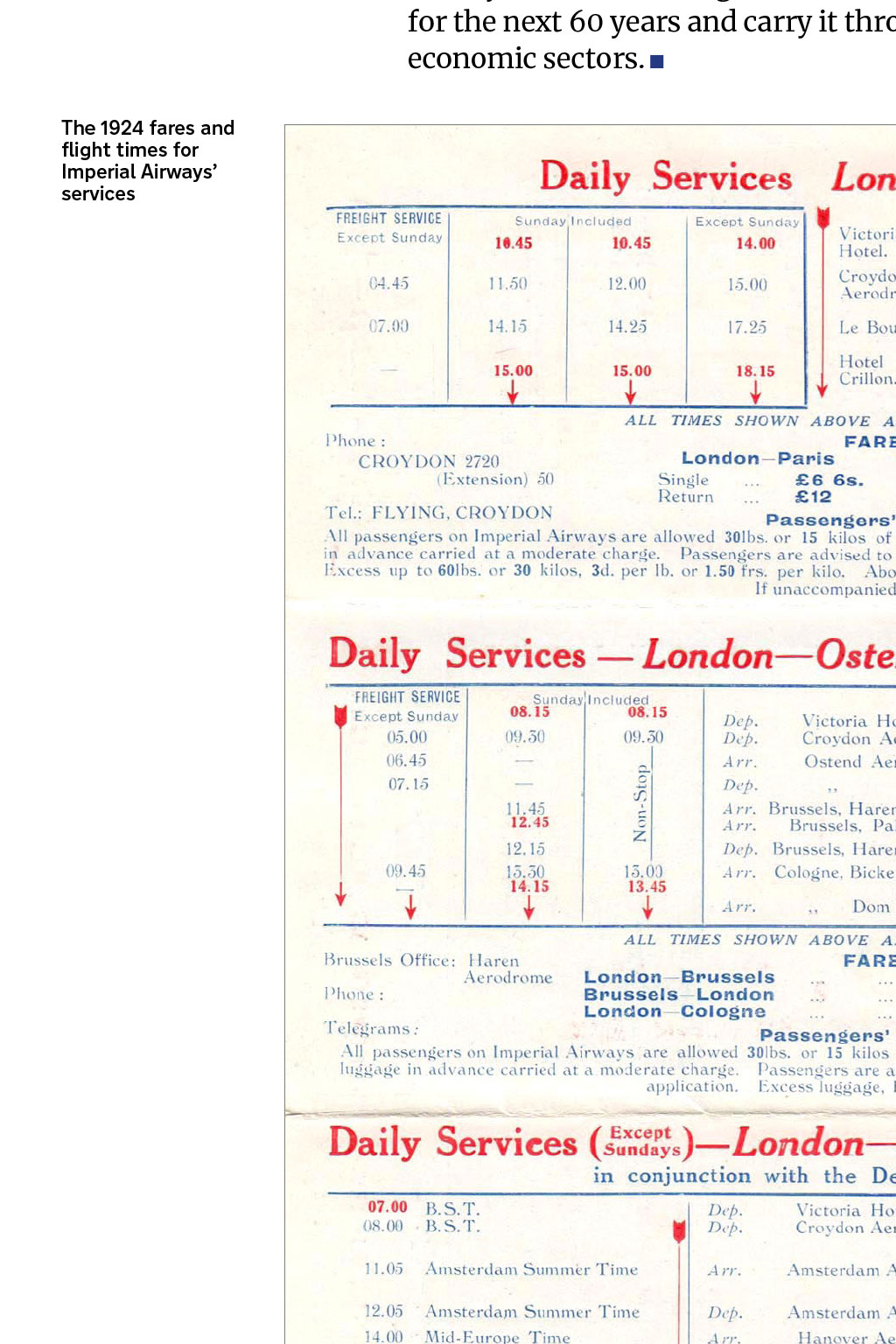

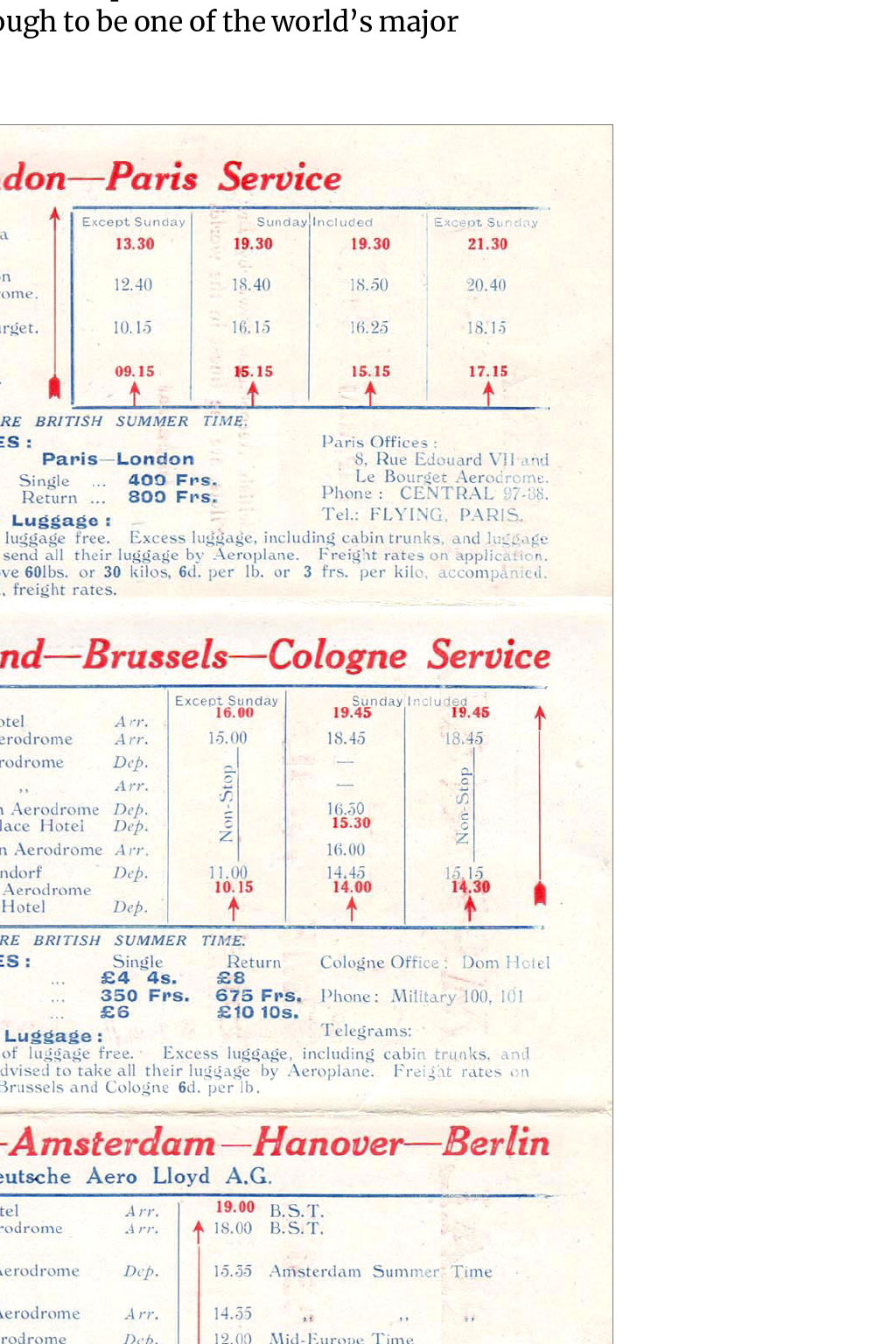

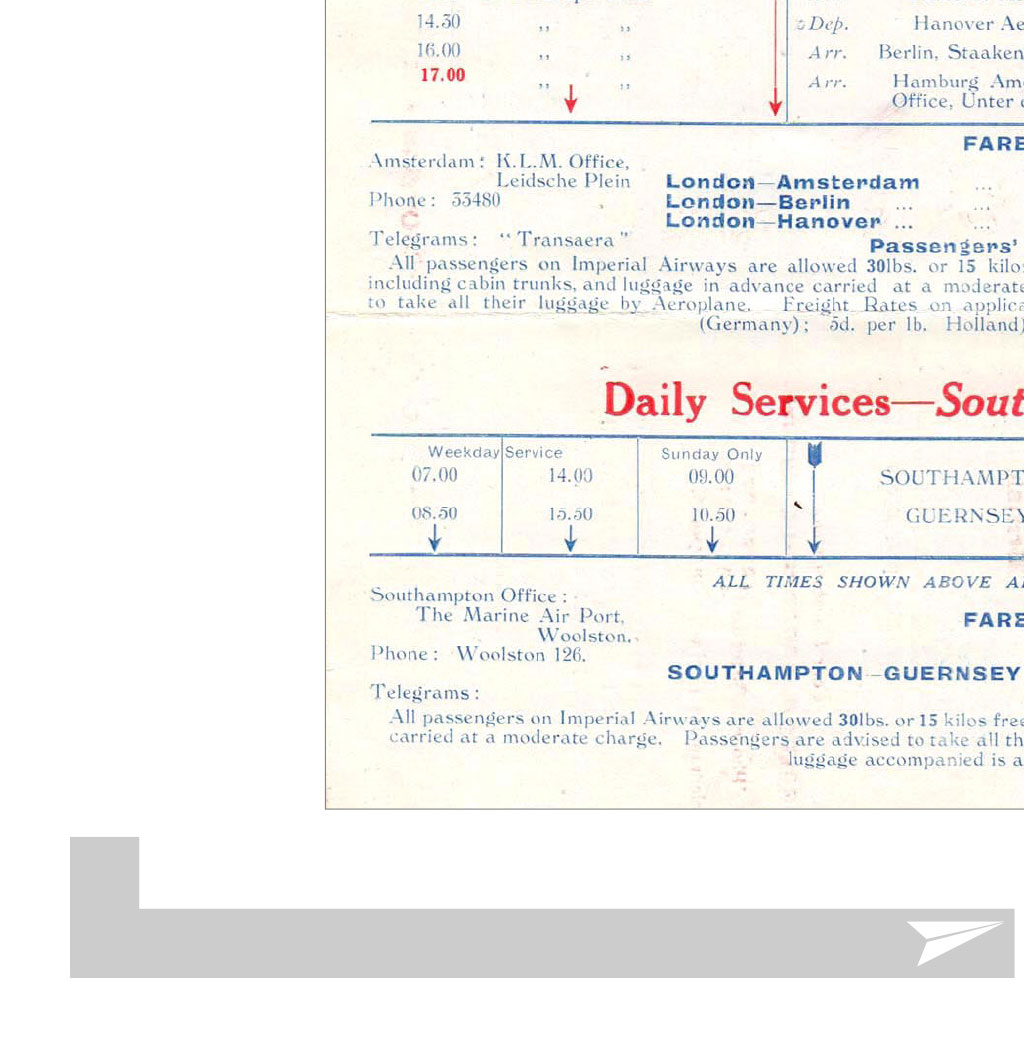

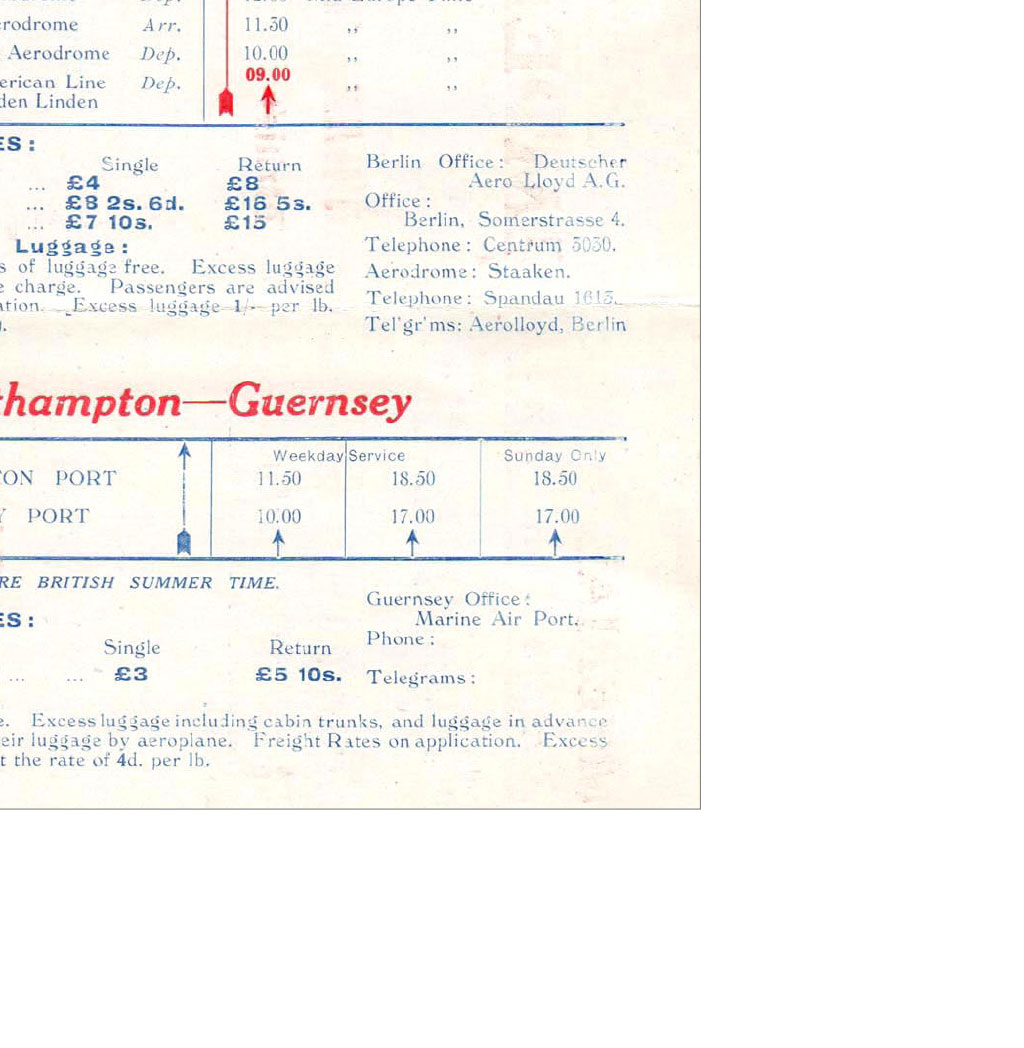

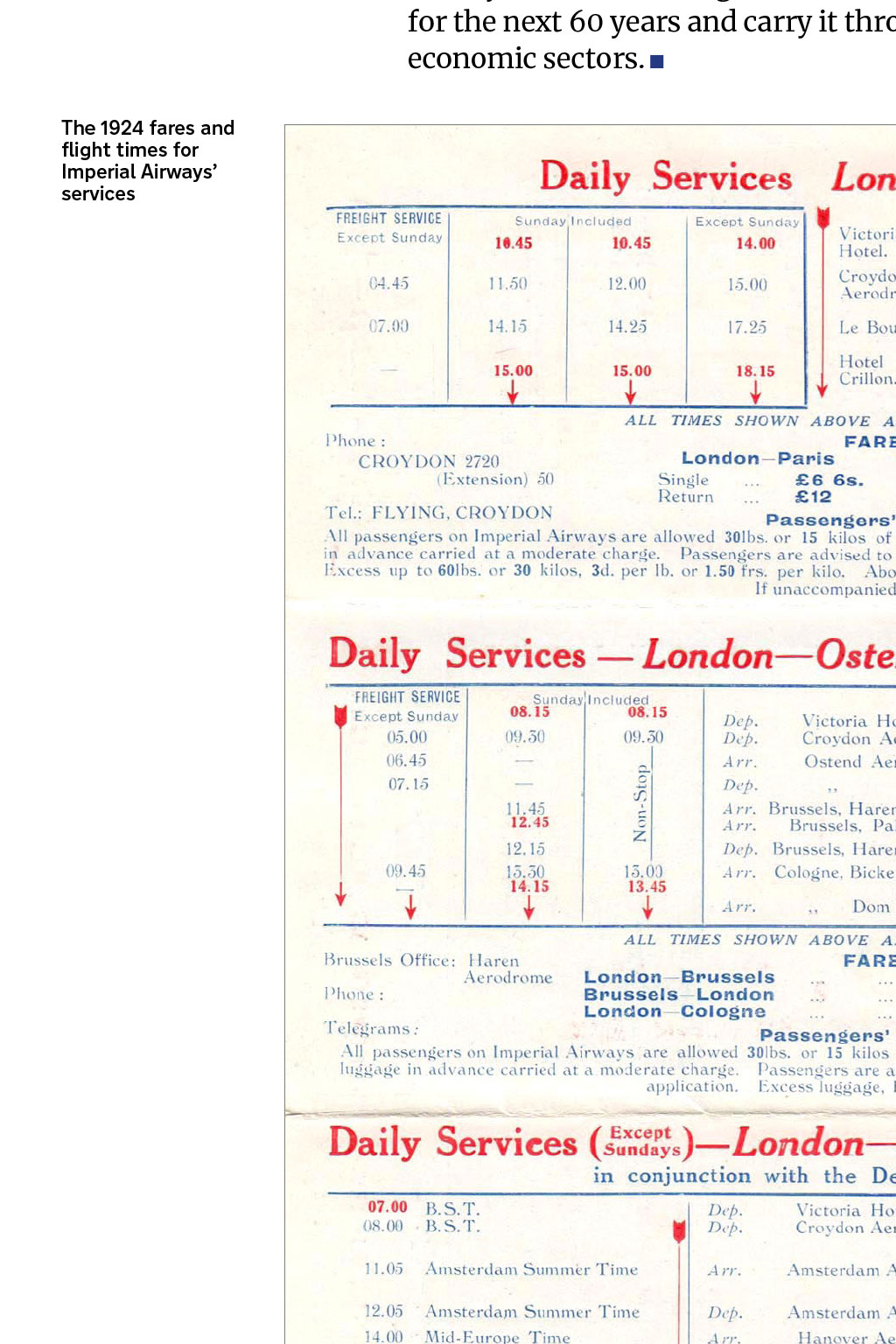

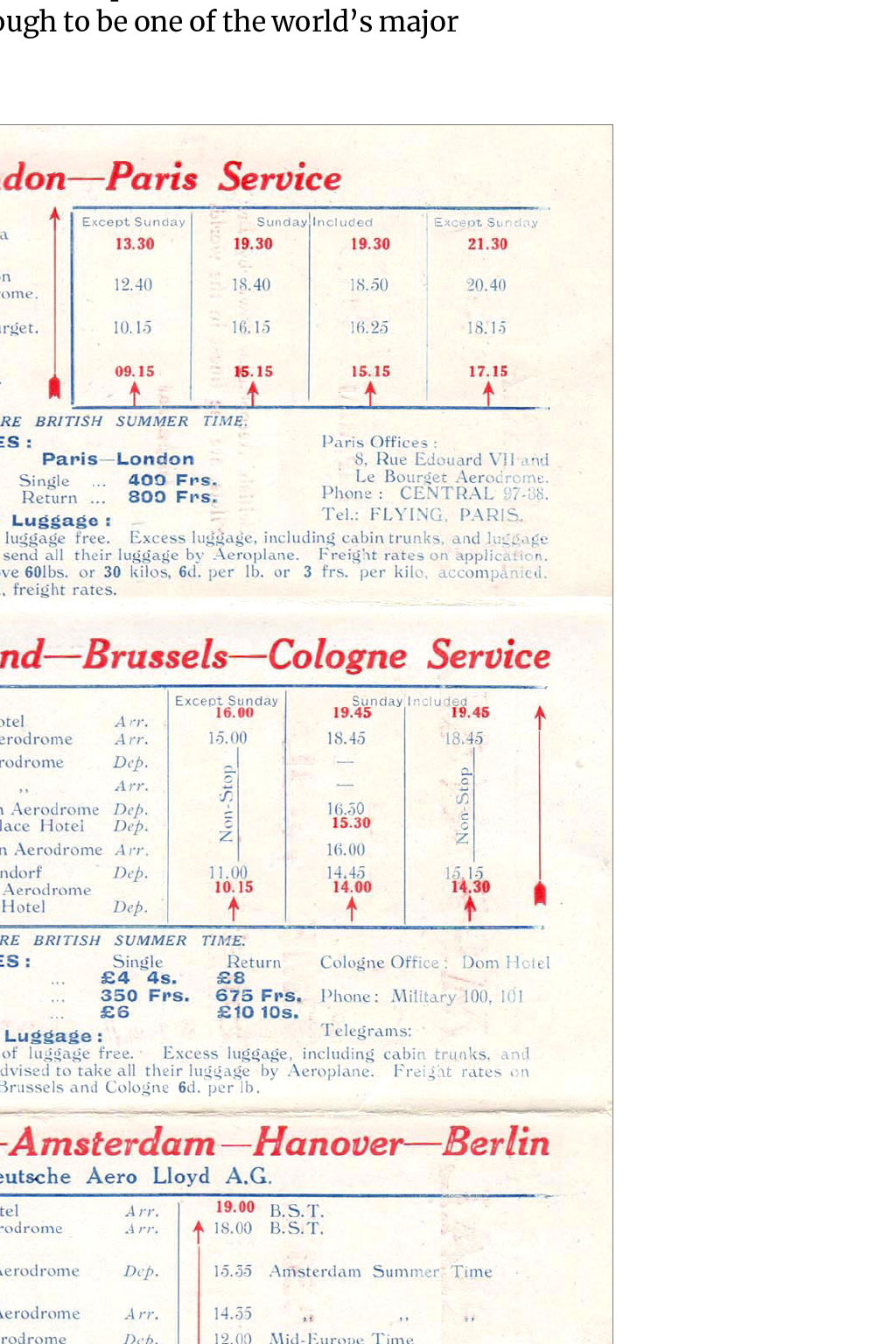

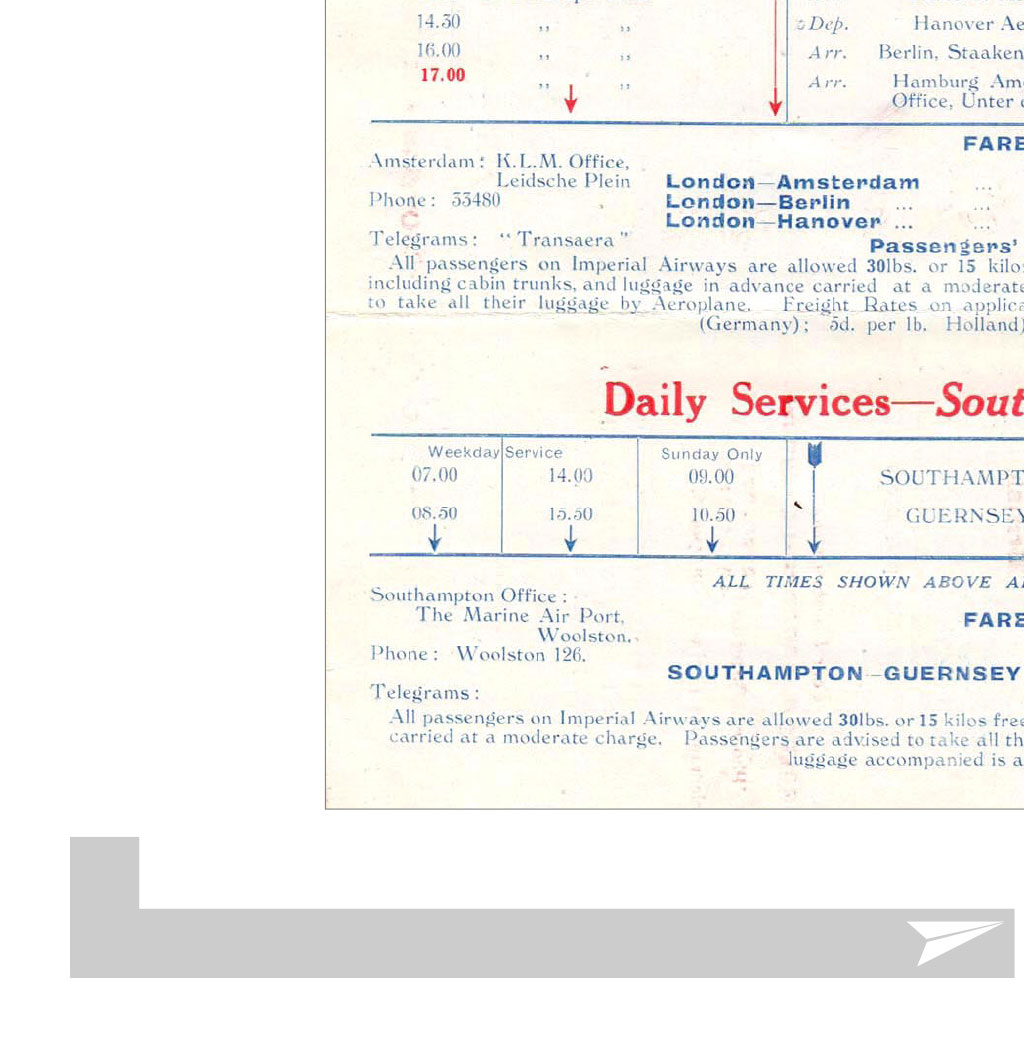

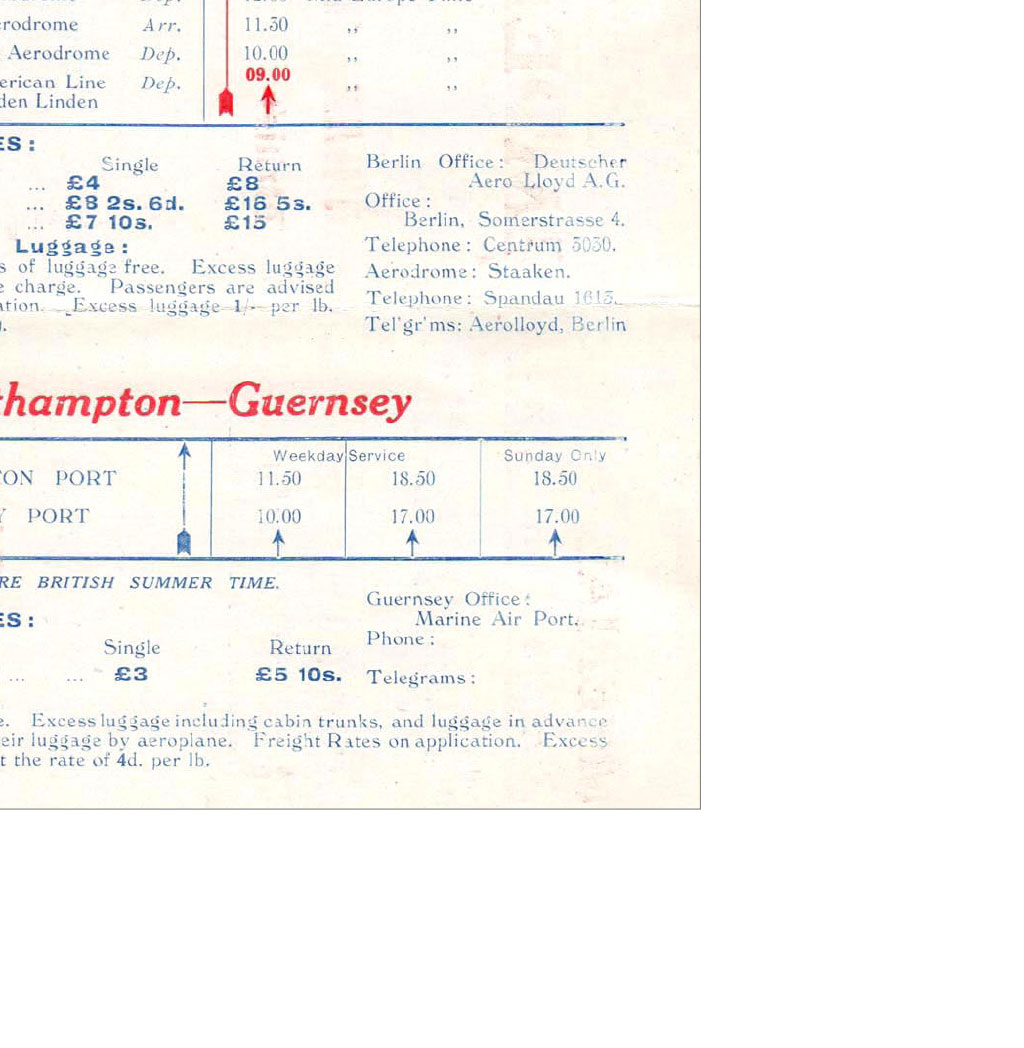

FLIGHT HISTORY The day Britain stopped flying. 2020 was not the first year that British flights were halted By Captain Ian Walker, Chair, Historic Croydon Airport Trust We have all borne witness to the devastation that COVID-19 has brought to our industry. For the air transport sector, particularly in the UK, it has been a nearterminal event, with the sector almost ending up in intensive care. The UKs aviation sector seems to have borne the brunt of COVID-19s economic fallout, with little in the way of support administered to help nurse it through the severity of the economic turbulence. Some of the statistics are well publicised: UK air traffic movements down 73% compared with 2019; 3,000 pilots made redundant; and, in July 2021, Britain made the top spot, with its three major airports achieving the dubious distinction of being the worst-affected airports in Europe. Gatwick, Manchester and Heathrow were cited as the biggest losers. All the metrics available show that the UKs air transport industry has been well and truly hammered. While the impact, globally, has been equally severe, how it has been managed has varied widely. In Europe, we have seen the air transport sector receive, in broad terms, substantive support. In Britain, we have found the approach to be somewhat different, with a divergence from the approach of most western governments. Although there has been much lobbying of government and ministers by our association, it has had little discernible effect in changing their collective minds and direction. The current response is a strong echo from events of 100 years ago, when British commercial air transport was brought to a grinding halt, with the finger of blame pointing to the government of the day. Turning back time Winding back the clock, autumn 1920 marked the end of a fairly successful first year of international air transport. After the launch of international scheduled services on the 25th August 1919, steady progress had been made. In March 1920, the temporary airport at Hounslow Heath was closed, and air transport operations moved to the larger and better equipped former World War One airfield at Croydon. By the end of 1920, 6,383 passengers had been transported on the newly inaugurated intercontinental air routes, which consisted of Paris, Brussels and Amsterdam. The three British airlines Aircraft Transport and Travel, Handley Page, and Instone Air Line had sprinted out of the starting blocks and were establishing a strong position on the three international routes across the English Channel. Around 91% of the cross-channel passengers were carried by the UK airlines, with 7.5% carried by French airlines and 1.5% by the Belgian airline. The fledging Dutch airline, KLM, was recorded as carrying nil passengers on its five movements on the route. While Britains independent airlines had performed well over the first year, the economic headwinds were building. Passenger traffic over the winter months showed a marked drop compared with the summer records. European aviation had learned that its market was seasonal. The visual navigation methods of the time were not compatible with attempting to operate scheduled air operations in northern European winters. Moreover, the effect of the differing national governmental policies towards aviation was beginning to have a financial effect. The Right Honourable MP for Dundee, Winston Churchill, had been appointed to the newly created position of Secretary of State for Air on the 10th January 1919, alongside his appointment as Secretary of State for War. An ardent free marketeer, Churchill stated that civil aviation must fly by itself and that the government cannot possibly hold it up in the air words and policy that would have significant consequences just 18 months later. Above: A summer 1924 timetable for Britains Imperial Airways Extensive remit In 1919, the Air Ministry, formed in 1918 to oversee the Royal Air Force, was also tasked with regulating and administering civil aviation. Its remit was extensive: surveying, issuing and regulating aerodrome licences; pilot, navigator and engineer licensing; aircraft airworthiness requirements; establishing and operating airport facilities; administration and operation of the Meteorological Office; installation of wireless facilities; and air accident investigation, to name but a few. One area for which the Air Ministry was not financially responsible was flight operations. These wide-ranging responsibilities were administered on a very modest budget one that was shared with the Royal Air Force, which consistently secured the lions share of available funding. Across the water in France, government policy towards commercial aviation was somewhat different. It was investing heavily in commercial air transport operations and giving substantial support to its international airlines, a position that was mirrored in Belgium and other European nations. The direct operating subsidies helped French carriers slash the airfares on the cross-channel routes to just 6 6s 0d for a single ticket half the cost that the UK airlines could offer. Lord Weir recommended to parliament that subsidies be paid to the British airlines on the cross-channel routes, but the recommendations fell on deaf ears. The fierce subsidised European competition began to have an acute effect on Britains fledging airlines, which experienced accelerating financial losses. With no financial help on the horizon, the first casualty of the cross-channel price war occurred on 17th December 1920, with Aircraft Transport and Travel ceasing operations. Its owner, the newspaper entrepreneur George Holt-Thomas, liquidated the company and the remnants of it were merged with Birmingham Small Arms Co Ltd. A sad end for one of the pioneer airlines, which had the accolade of operating the worlds first scheduled international air service. The two remaining British airlines were also feeling the heat of subsidised competition. With no sign of government support and spiralling losses, their financial position became precarious. On 28th February, Handley Page and Instone Air Line suspended operations. There were now no British airlines operating commercial international services. Any questions? Questions were raised in parliament and the point was made that the Air Ministry was now providing airport, wireless, navigation, meteorological and administration services wholly for the benefit of foreign competitors funded solely by the British taxpayer. The press was critical of the governments approach. An editorial in The Aeroplane summarised the issue: British civil aviation died with the cessation of the Handley Page cross-channel service, killed by the forward policy of the French government and the apathy of our own. A parliamentary committee was rapidly brought together to agree a temporary subsidy scheme for the two British operators. Funding to a maximum value of 88,200 was agreed as an interim measure to restart the British cross-channel air services, covering the period to the end of March 1922. Handley Page resumed services on 19th March 1921, with Instone Air Line following on 21st March. Because of the subsidy conditions, it was nigh on impossible for the British airlines to claim the subsidy in full. In contrast, the French government granted subsidies for their airlines to the sum of 1,328,600 more than 15 times the British funding level. The poor financial position of civil air transport became a hot topic of debate in parliament. Questions were raised as to the allocation of the Air Estimates budget for the Air Ministry. Of the 18m of funds allocated, only 880,000 was granted for civil aviation most of the finance package was earmarked for the RAF. Of the 880,000 civil aviation budget, only 60,000 was for flight operations the remainder was for staff, facilities, administration, and operating costs. The [governments] initial indifference and apathy had dealt a self-inflicted, near-mortal wound to the fledgling air transport sector The newly elected MP for Harrow, Oswald Mosley, gave a speech to parliament in April 1921, highlighting the stark difference in approach by the UK government compared with its French counterpart. Addressing the Secretary of State for Air, and the House, he said: We find ourselves in the lamentable position of only placing 60,000 at the disposal of the honourable gentleman for subsidising the great air routes, and the result, as he has told us this afternoon, is that only one aeroplane will journey each way each day. At the same time, France is allocating to civil aviation 3,400,000 at the present exchange rates, which, at pre-war exchange, would be 7,000,000, and of this sum at the present rate of exchange 600,000 is allotted to aerial transport. It is hopeless for our paltry 60,000 to hope to compete with this sort of thing. The government had given too little, too late. Sir William Joynson-Hicks voiced support for Mosleys points. It is quite true that things are in a bad state at the present time. You cannot expect a baby to run unless you give it some help. Churchill seems to have had a change of heart with regards to supporting commercial air transport, and responded by saying this baby has got to fly. The cross-channel statistics for the end of 1921 detailed the extent of the damage to Britains air routes. Daimler Airway had entered the fray in April 1922, using the assets it had inherited from the defunct Aircraft Transport and Travel Ltd, joining Handley Page and Instone Air Line competing on the international air routes. While total passenger traffic on the route for the year had grown to 10,731, Britain had seen a significant shrinkage in its market share. UK total passenger traffic was down a modest 9%, but aircraft movements had dropped a massive 65%, to 993. The French, Belgian and Dutch airlines had all had a significant improvement in their market share. French aircraft movements had grown to 1,565, while passenger traffic had a near nine-fold increase, rising to 4,352. Belgian and Dutch traffic were all up in similar ratios. While the temporary subsidy schemes for the UK airlines went some way to shield the British airlines from the full effect of its competitors subsidies, the schemes conditions meant the full subsidy could not be achieved. Even so, by the end of 1922, the three UK operators were able to recapture some market share, with 65% of the cross-channel passengers and 41% of the cargo. Joint effort The question of subsidies would not go away. The late realisation by the government that subsidies were necessary was welcomed, but the initial indifference and apathy had dealt a self-inflicted, near-mortal wound to the fledgling air transport sector. Eyes turned across the channel to European methodology, with a growing realisation that a temporary scheme would not solve a permanent problem. In 1923, a parliamentary committee, headed by Sir Herbert Hambling, was formed to investigate the problems faced by Britains airlines and to find a more permanent solution. It concluded that one monopolistic limited company, government-sponsored, would be the most desirable outcome to provide longer-term financial stability for the sector. A 1m subsidy was offered to merge the three Croydon-based airlines and a Hamble-based flying boat company into one corporate entity. After nine months of discussions with the four operators, negotiations were concluded, and Britains national flag carrier airline was born. On the 31st March 1924, the government-backed Imperial Airways came into being. Subsidised air transport would be the norm for the next 60 years and carry it through to be one of the worlds major economic sectors. The 1924 fares and flight times for Imperial Airways services