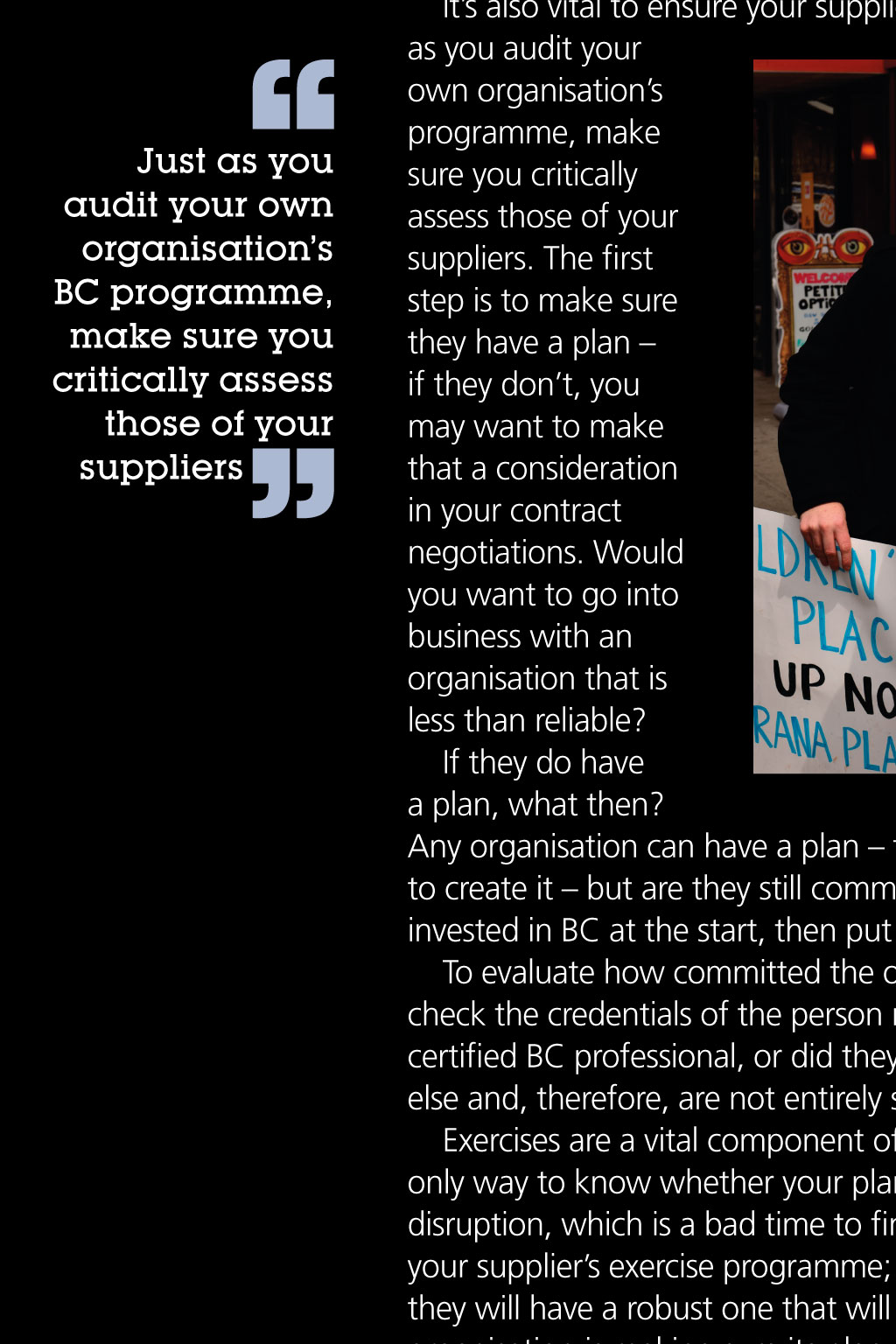

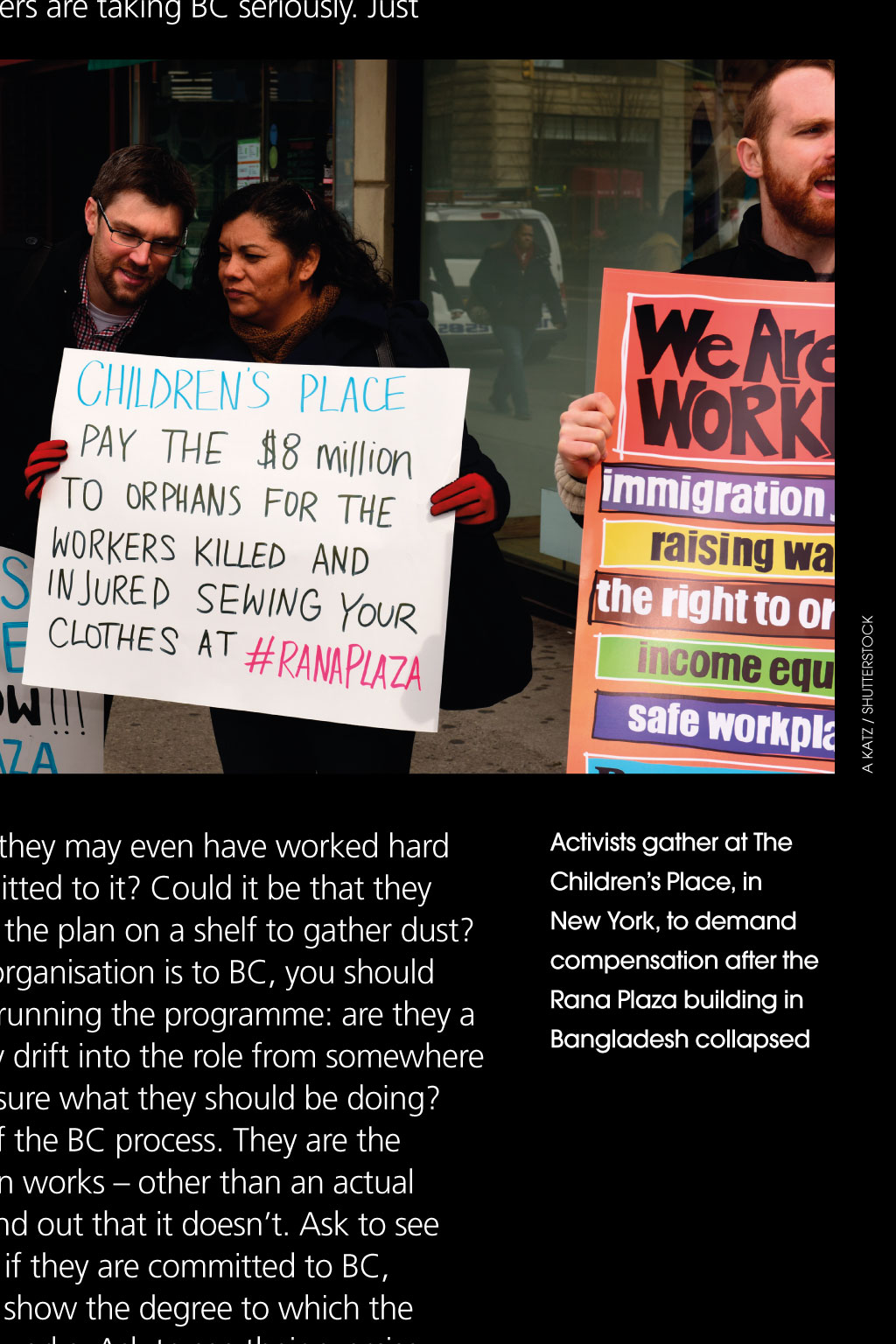

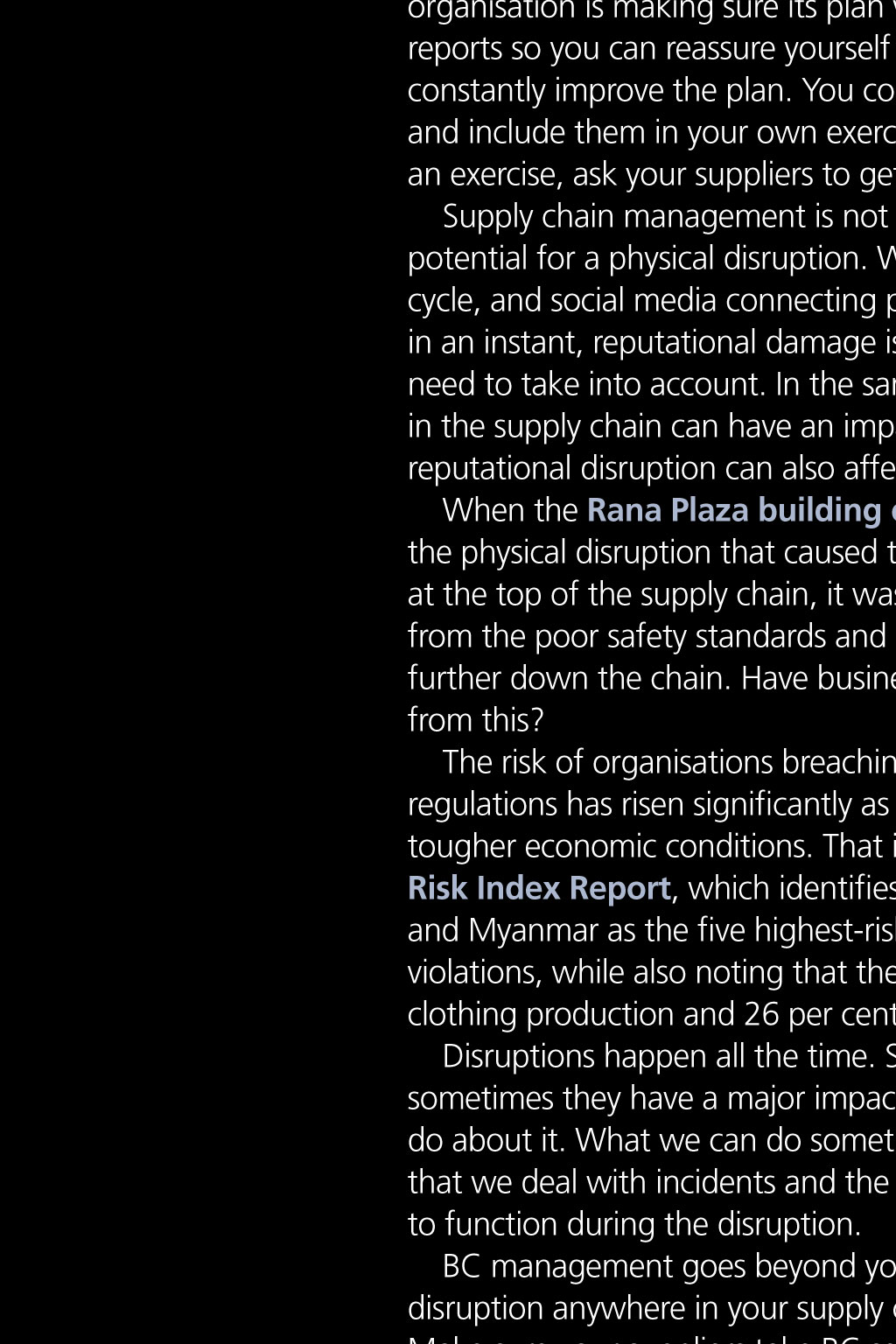

suppLy ChaIns TakIng seRIOusLy pAul prescott / shutterstocK RISk TO SUPPLy CHAInS COMES In MAny fORMS, InCLUDInG HOW SERIOUSLy SUPPLIERS TAkE THE THREAT Of DISRUPTIOn TO THEIR OWn BUSInESSES, SAyS ANDREW SCOTT, Of THE BUSInESS COnTInUITy InSTITUTE Just as you audit your own organisations Bc programme, make sure you critically assess those of your suppliers T The five highest-risk countries for human rights violations also account for 48 per cent of global clothing production A KAtz / shutterstocK Andrew Scott is the senior comms manager for The Business Continuity Institute. In November 2014, he passed his Certificate of the BCI exam with merit he Business Continuity Institutes (BCIs) latest Supply Chain Resilience report showed that 76 per cent of respondents had experienced at least one supply chain disruption during the previous 12 months. Nearly a quarter claimed their organisation had suffered losses of at least 1m during that time, which shows just how costly a disruption can be if you are unable to manage it effectively. So what can be done to make a supply chain more resilient? In the same way that you would conduct a horizon scan to assess the threats to your own organisation, you should also consider some of the threats to your suppliers. If you know what they are, you can try to mitigate against them. Location is often a major factor in determining potential risks. If you have suppliers in the Middle East, then security or terrorism may be the greater threat, but in the Far East it could be human illness. If your suppliers are in south-east Asia, theres a greater likelihood of a natural disaster causing a disruption; in western Europe, its probably more likely to be an industrial dispute. Get to know your supply chain and the threats contained within it. If you are to take the threat to your supply chain seriously, so you can take action against it, the first thing you need to consider is your top managements commitment to supply chain resilience. Unfortunately, it can often be difficult to convince them of the importance of making your own organisation resilient. You will need to draw on the other returns on investment that effective business continuity (BC) can offer, rather than focus simply on the ability to survive a crisis that may or may not happen. Even if you succeed in doing this, demonstrating why you also need to ensure that other organisations are resilient can be a challenge too far. There is, however, a wealth of information online that helps show the value for money of BC and supply chain resilience. Its also vital to ensure your suppliers are taking BC seriously. Just as you audit your own organisations programme, make sure you critically assess those of your suppliers. The first step is to make sure they have a plan if they dont, you may want to make that a consideration in your contract negotiations. Would you want to go into business with an organisation that is less than reliable? If they do have a plan, what then? Any organisation can have a plan they may even have worked hard to create it but are they still committed to it? Could it be that they invested in BC at the start, then put the plan on a shelf to gather dust? To evaluate how committed the organisation is to BC, you should check the credentials of the person running the programme: are they a certified BC professional, or did they drift into the role from somewhere else and, therefore, are not entirely sure what they should be doing? Exercises are a vital component of the BC process. They are the only way to know whether your plan works other than an actual disruption, which is a bad time to find out that it doesnt. Ask to see your suppliers exercise programme; if they are committed to BC, they will have a robust one that will show the degree to which the organisation is making sure its plan works. Ask to see their exercise reports so you can reassure yourself that they are doing their best to constantly improve the plan. You could even take this one step further and include them in your own exercise programme. If youre planning an exercise, ask your suppliers to get involved. Supply chain management is not just about being aware of the potential for a physical disruption. With the modern eras 24-hour news cycle, and social media connecting people who can share information in an instant, reputational damage is something that organisations need to take into account. In the same way that a physical disruption in the supply chain can have an impact on all those within it, a reputational disruption can also affect everyone. When the Rana Plaza building collapsed in Bangladesh, it wasnt the physical disruption that caused the most damage to organisations at the top of the supply chain, it was the reputational damage resulting from the poor safety standards and human rights abuses taking place further down the chain. Have businesses learned their lessons from this? The risk of organisations breaching international human rights regulations has risen significantly as key Asian economies adapt to tougher economic conditions. That is the conclusion of the BSIs RiskIndex Report, which identifies China, India, Vietnam, Bangladesh and Myanmar as the five highest-risk countries for human rights violations, while also noting that they account for 48 per cent of global clothing production and 26 per cent of electronics exports. Disruptions happen all the time. Sometimes they are small, but sometimes they have a major impact. Theres very often nothing we can do about it. What we can do something about, however, is the way that we deal with incidents and the plans we have in place to allow us to function during the disruption. BC management goes beyond your own organisation, because a disruption anywhere in your supply chain could have an impact on you. Make sure your suppliers take BC seriously, so they can cope with disruption as well as you can. Make it part of contract negotiations and involve them in your own BC management process to reassure yourself that they are fully committed and not just box ticking. Activists gather at The Childrens Place, in New York, to demand compensation after the Rana Plaza building in Bangladesh collapsed