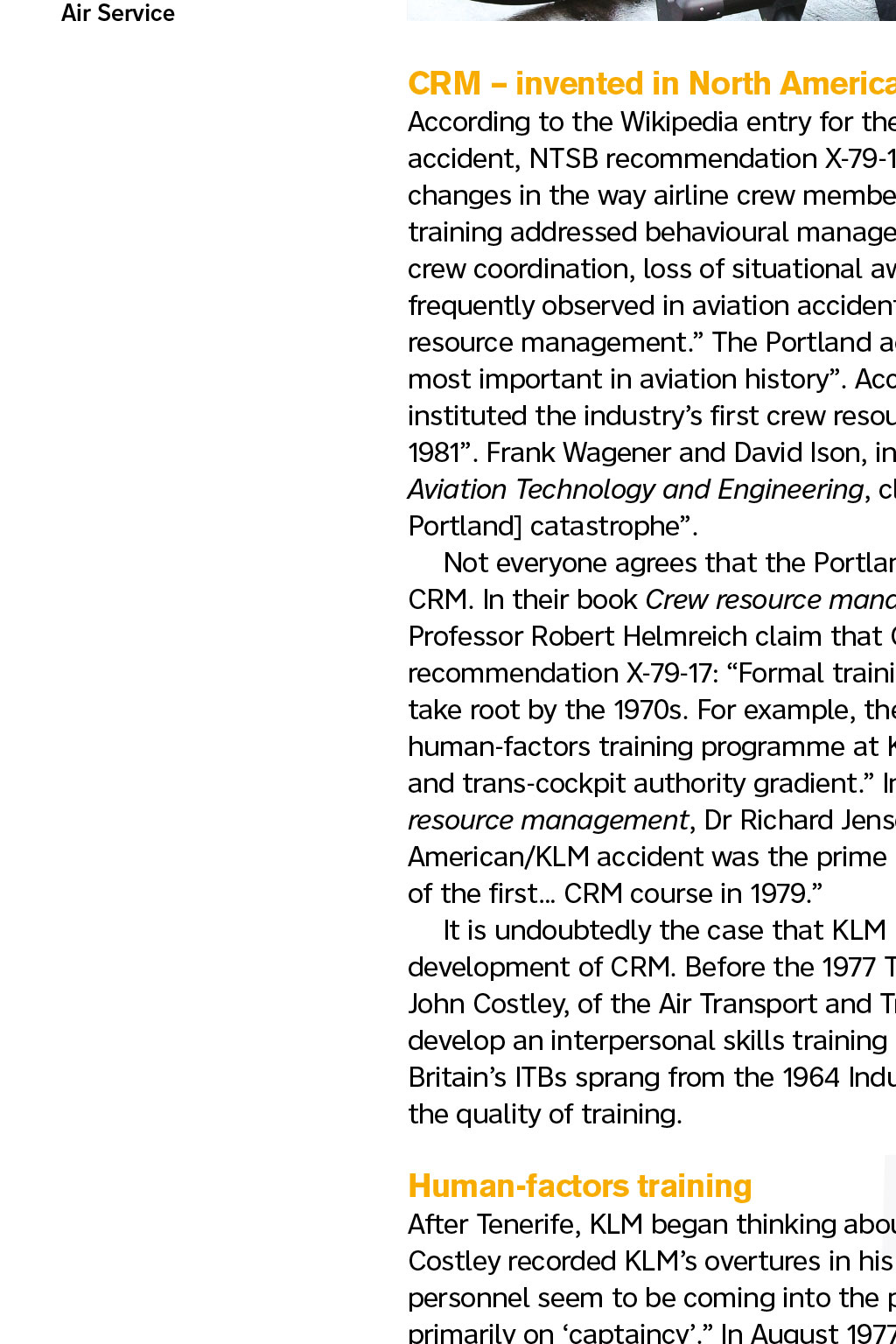

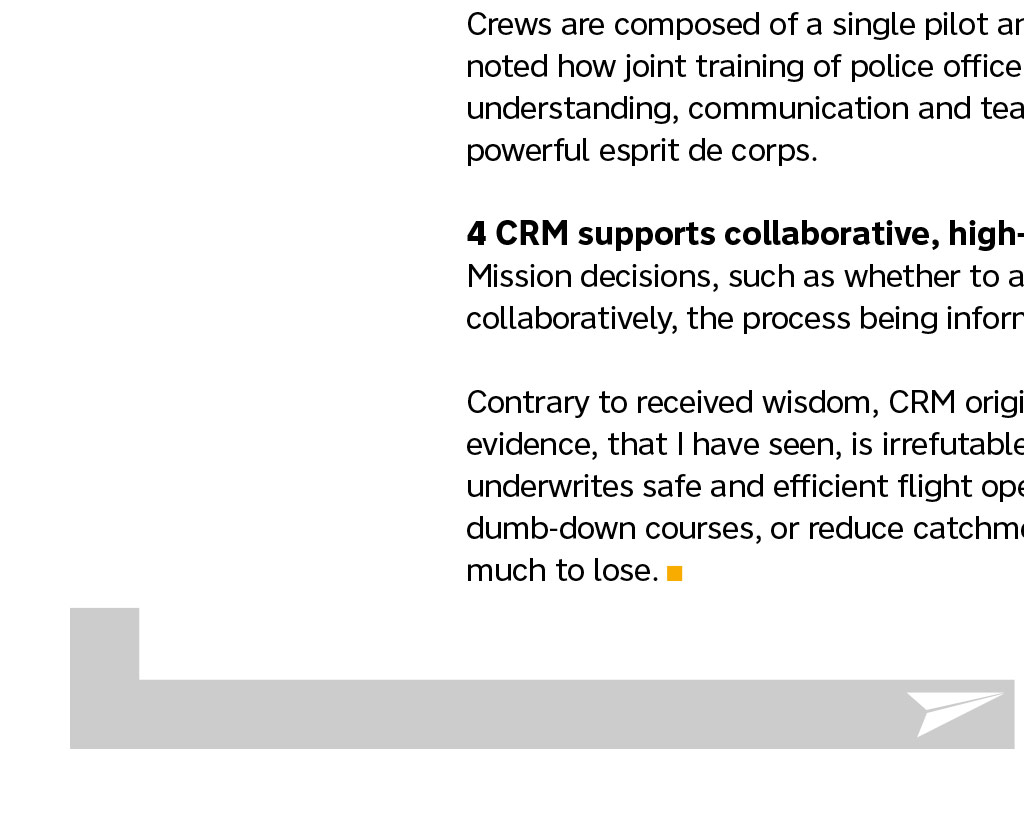

We take a look at the origins and impact of crew resource management By Dr Simon Bennett, Director, Civil Safety and Security Unit, University of Leicester rew resource management (CRM) specifies the skills, attitudes and behaviours required of pilots, cabin crew, dispatchers, engineers, handlers and controllers to ensure trouble-free operations. Required skills, attitudes and behaviours include professionalism, leadership, awareness, curiosity, inquiry, flexibility, collegiality, respectfulness, empathy, orderliness, alacrity, modesty, and a capacity for reflection and self-deprecation. These skills are required of all, from novice dispatchers to time-served training captains and hard-bitten fleet managers. In a 1989 report titled Aeronautical decision-making cockpit resource management, Dr Richard Jensen attributed the birth of CRM to 10 disasters, specifically: 1. Eastern Air Lines, L-1011 Tristar, Miami, 1972 The crew of three, preoccupied with a malfunctioning nose-gear indicator light, failed to notice that the autopilot had disconnected, and that the aircraft was descending. Death toll: 101 2. TWA, B-727, Washington Dulles, 1974 Ambiguous communications between the crew and controllers resulted in the aircraft hitting Mount Weather. The National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), in its 1975 report, drew attention to the failure of the FAA to take timely action to resolve the misinterpretation of air traffic terminology, although the Agency had been aware of the problem for several years. Death toll: 92 3. Pan American and KLM, B-747s, Tenerife, 1977 Ambiguous communications between the KLM crew and controllers, in the context of operational pressures, resulted in the KLM 747 starting its take-off roll without clearance. Death toll: 583 4. United Airlines, DC-8 Jet Trader, Salt Lake City, 1977 Ambiguous communications between the crew and a controller, in the context of distracting malfunctions several landing-gear lights were inoperative resulted in the aircraft hitting a mountain. Death toll: three 5. United Airlines, DC-8, Portland, 1978 Crew members failure to monitor fuel-state during a landing-gear emergency led to fuel exhaustion. The NTSBs report noted: [T]his accident exemplifies a recurring problem a breakdown in cockpit management and teamwork during a situation involving malfunctions of aircraft systems To combat this problem, responsibilities must be divided among members of the flight crew while a malfunction is being resolved. Recommendation X-79-17 requested that the FAA [U]rge operators to ensure that flight-crews are indoctrinated in principles of flight-deck resource management, with particular emphasis on the merits of participative management for captains and assertiveness training for other cockpit crew members. Death toll: 10 6. National Airlines, B-727, Escambia Bay, 1978 Lax flight-deck discipline, overconfidence, complacency, and poor crew coordination and intra-crew communication, in the context of an ATC-induced rushed approach and elevated work-rate, resulted in the aircraft being flown into the ocean. Death toll: three 7. Western Airlines, DC-10, Mexico City, 1979 A misjudged go-around, in the context of non-standard ATC advisories concerning a sidestep manoeuvre and inadequate documentation for that manoeuvre, resulted in the aircraft crashing on the airfield. Death toll: 72 (aircraft); one (ground) 8. Dan-Air, B-727, Tenerife, 1980 Pilot error, in the context of sub-standard ATC for example, tardiness and the issuing of an ambiguous instruction and approach-planning that created latent errors, resulted in the aircraft hitting a mountain. Death toll: 146 9. Saudia, L-1011 Tristar, Jeddah, 1980 A cargo-hold fire required an emergency landing. Despite the presence of smoke and fumes in the cabin, the crew failed to initiate an evacuation. The aircraft was taxied and parked, and was destroyed by a flash fire. Elapsed time between touchdown and flashover was around 31 minutes. Poor teamwork may have contributed to the disaster. Death toll: 301 10. Air Florida, B-737, Washington National, 1982 Sub-standard CRM, in the context of false indications from the engine instrumentation, and ATC pressure to get flights back on schedule, resulted in the aircraft rotating with ice on the wings, climbing a few hundred feet, then falling into the Potomac. The NTSB criticised the captains response to the first officers comments about the aircrafts sluggish acceleration. Death toll: 74 (aircraft); four (Potomacs 14th Street Bridge). Simon Bennett with the UK National Police Air Service CRM invented in North America? According to the Wikipedia entry for the 1978 United Airlines Portland accident, NTSB recommendation X-79-17 was the genesis for major changes in the way airline crew members were trained. This new type of training addressed behavioural management challenges, such as poor crew coordination, loss of situational awareness, and judgement errors frequently observed in aviation accidents. It is credited with launching crew resource management. The Portland accident is described as one of the most important in aviation history. According to Wikipedia, United Airlines instituted the industrys first crew resource management (CRM) for pilots in 1981. Frank Wagener and David Ison, in a paper published in the Journal of Aviation Technology and Engineering, claim that CRM was born from [the Portland] catastrophe. Not everyone agrees that the Portland accident was the catalyst for CRM. In their book Crew resource management, H Clayton Foushee and Professor Robert Helmreich claim that CRM was born before the issuance of recommendation X-79-17: Formal training in human factors was beginning to take root by the 1970s. For example, the late Frank Hawkins had initiated a human-factors training programme at KLM based on Edwards SHEL model and trans-cockpit authority gradient. In his book Pilot judgement and crew resource management, Dr Richard Jensen writes: The [March 27 1977] Pan American/KLM accident was the prime motivator behind KLMs development of the first CRM course in 1979. It is undoubtedly the case that KLM played a pivotal role in the development of CRM. Before the 1977 Tenerife disaster, KLM had worked with John Costley, of the Air Transport and Travel Industrial Training Board (ITB), to develop an interpersonal skills training course for check-in staff and pursers. Britains ITBs sprang from the 1964 Industrial Training Act, intended to improve the quality of training. Human-factors training Observing NPAS operational sorties from the jump seat After Tenerife, KLM began thinking about human-factors training for pilots. Costley recorded KLMs overtures in his work diary: [5th July, 1977] [C]ockpit personnel seem to be coming into the picture, although it seems to be primarily on captaincy. In August 1977, KLMs Flight Operations and Training Department began working on a human-factors training programme for captains. Costley wrote: [2nd August, 1977] Flight Ops meeting at top level in KLM to talk about captaincy training. Project to start with wide investigation into what captain does from a management point of view. High-prestige project with Jan de Jong involved throughout. After joining KLM in 1968 as a marketing specialist, De Jong was told to, in his own words, improve the personnel services within KLM through training and consultancy. To that end, he worked with Costley by now the managing director of Interaction Trainers (IT) KLMs Alwin Maan Voogd Bergwerf, the KLM pilot group, and the Vereniging Nederlandse Verkeersvliegers (Dutch Pilot Association) to develop KLMs Captaincy Development Programme (CDP), an innovative human-factors programme that improved flight-deck leadership and management skills. According to Maan Voogd Bergwerf, the skills, attitudes and behaviours covered in the CDP included communication, decision-making, delegating and reporting skills. Teaching involved group exercises, which were videotaped, then analysed by participants. The first courses took one week. The catchment was expanded to include first officers and flight engineers, the name changing from CDP to crew management training (CMT). As Stephen Walsh, of IT, notes, KLMs flight engineers lobbied hard to be included in the new programme: The flight engineers kicked up a massive fuss. They said: Hang on a second. It was our engineer whose questions were rebuffed and dismissed by Van Zanten, the [KLM Tenerife] captain, so if the captains are having it, we are having it. Apparently, they were threatening to go on strike... Once the engineers kicked up this fuss, KLM turned around and said, OK. Everybody is having it. Clients for KLMs human-factors training included Kuwait Airways, South African Airways, Martinair, Transavia, Ansett, Qantas, SAS and the Dutch government (which sent its flight operations inspectors to be trained). The airline sent Costley to NASAs 1979 San Francisco human-factors workshop, Resource management on the flightdeck (NASA CP-2120). The workshop proceedings noted that the fostering of increased awareness and use of available resources by aircrews under high workload conditions is becoming a matter of greater concern to the airlines. New research and training programmes to enhance aircrew capabilities are being developed, largely independently, by the various organisations involved. They also noted a need to develop more effective resource-management training for flight-deck crew members. KLM had been doing this for some time. Some observations on CRM The first courses took a week, and involved group exercises, which were videotaped, then analysed by participants During my 22-year career in aviation safety, I frequently used in vivo research to critique CRM. I recently spent time with the UK National Police Air Service, where I attended CRM ground schools, interviewed flight crew and observed operational sorties crimefighting and intelligence gathering from the jumpseat. My major observations were: 1 The CRM skillset helps flight crew overcome challenges Crews are frequently confronted by challenging and shocking situations, from widespread civil disorder, such as the English riots of 2011, to murders or mutilations witnessed live on aircraft monitors. Crew members claimed that CRM, by structuring on-board interactions and activities, helped them negotiate survive harrowing situations. One of the frustrations is that crew can only bear witness to such events. They cannot intervene. 2 CRM encourages mindful behaviour Mindful (aware) behaviour creates safety and enhances performance. Crew members claimed that, because CRM made them more aware of their own and colleagues strengths and weaknesses, they were able to improve their own performance and that of colleagues. Mindfulness is positively linked to safety and efficiency. 3 Inclusive CRM training promotes safety and efficiency Crews are composed of a single pilot and two police officers. The author noted how joint training of police officers and pilots in CRM helped improve understanding, communication and teamwork. Further, it helped create a powerful esprit de corps. 4 CRM supports collaborative, high-quality decision-making Mission decisions, such as whether to accept a job (task), were made collaboratively, the process being informed and facilitated by CRM. Contrary to received wisdom, CRM originated in Europe. The documentary evidence, that I have seen, is irrefutable. Crew resource management underwrites safe and efficient flight operations. Pressures to shorten or dumb-down courses, or reduce catchments, must be resisted. We have too much to lose.