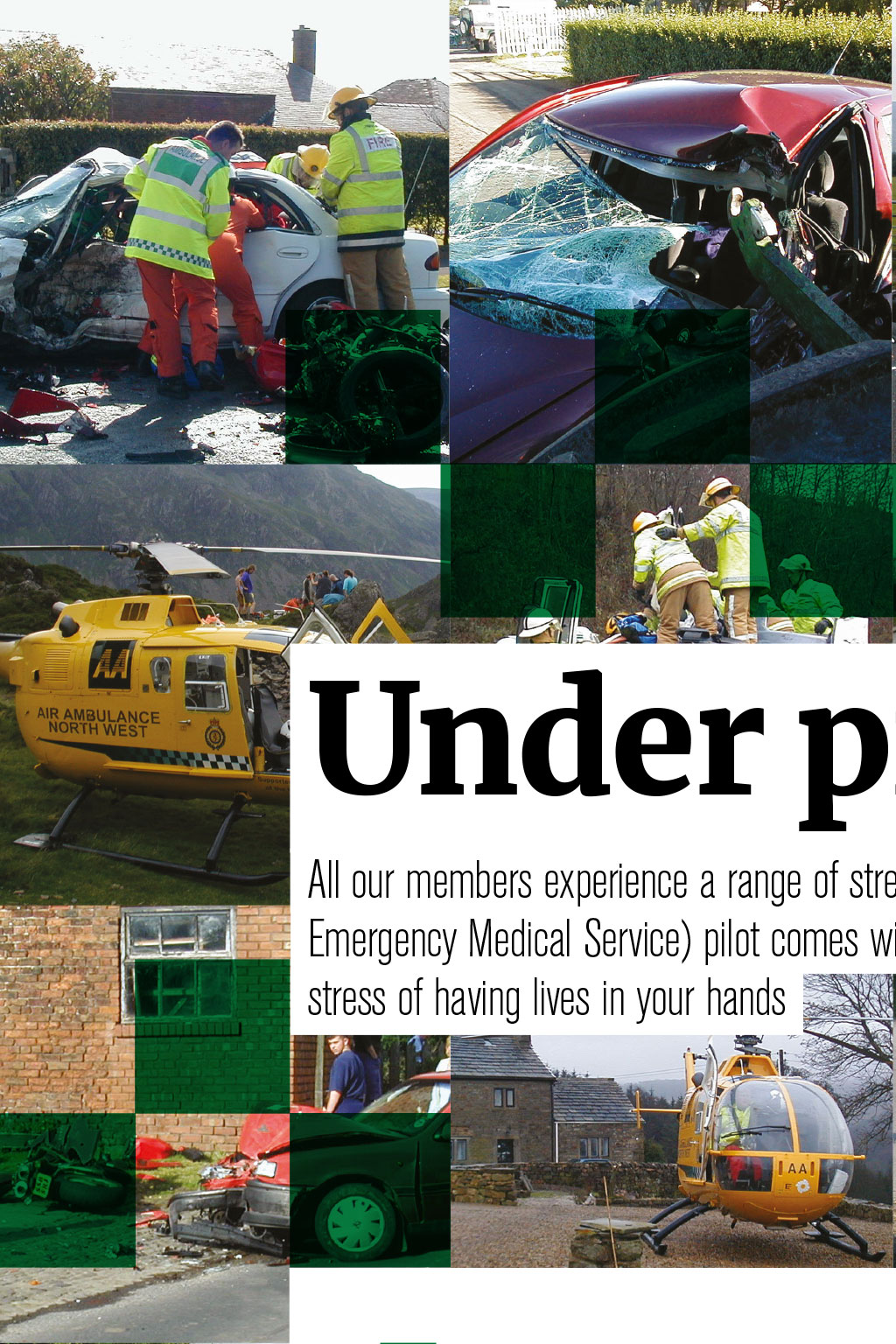

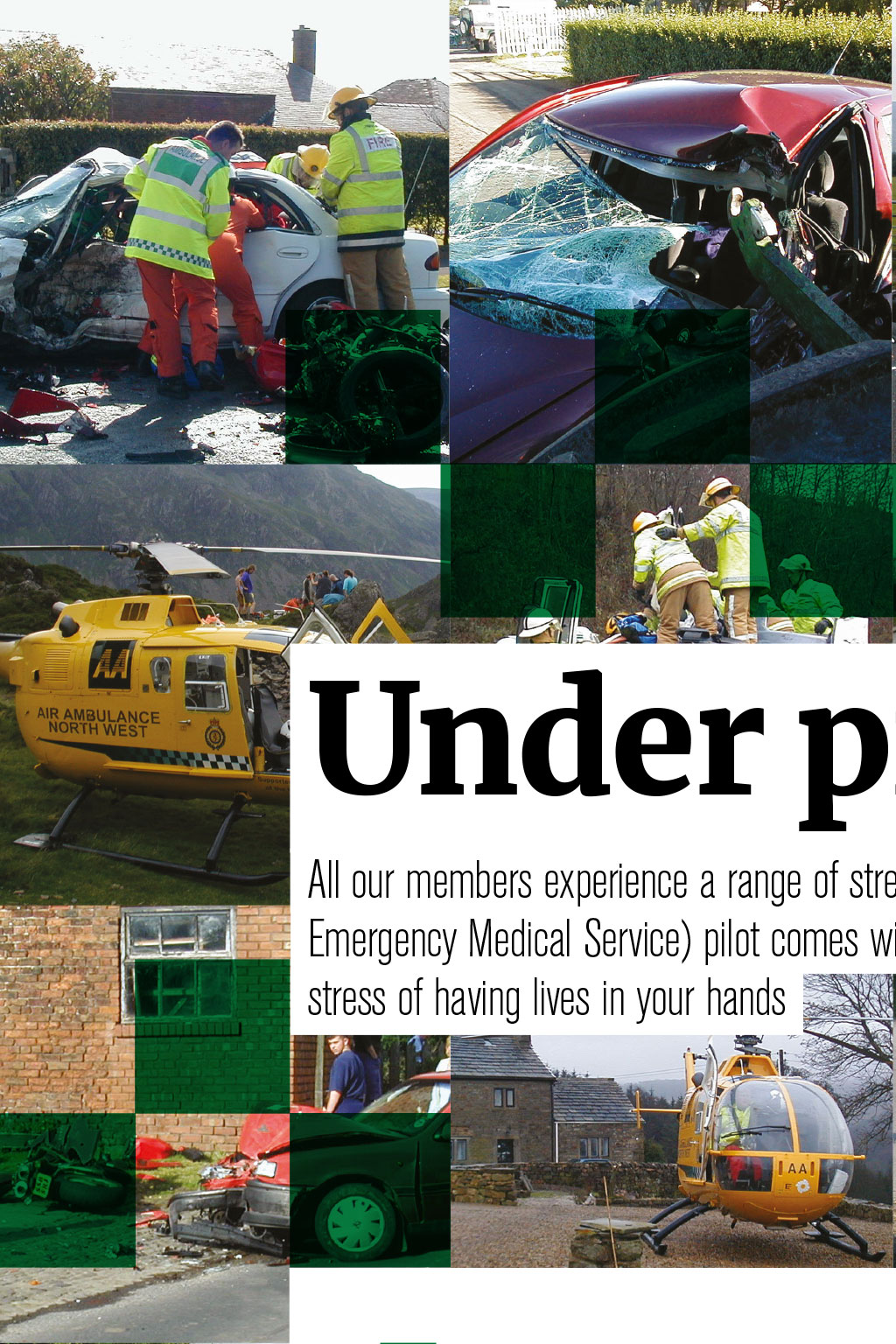

Under pressure All our members experience a range of stressors, but being a HEMS (Helicopter Emergency Medical Service) pilot comes with its own issues – including the inevitable stress of having lives in your hands By Owen McTeggart, BALPA member Mike Buckley READ MORE HEMS pilot Mike Buckley Knowing that the choices we make can be the difference between life and death brings with it an enormous weight of responsibility. The general awareness of this pressure within our community is very good. There is no point rushing to the aircraft without taking into account our own safety, the weather, the best route, how close we can get and how serious the injury is. We discuss this as a crew and make a plan. If there is a serious injury in a difficult location, we may accept increased risk while maintaining the safety of the crew, aircraft and other users of the fells. However, if the injury is not an immediate threat to life, we will offload some risk by landing further away, with the doctor and paramedic walking to the patient. . Risk factors We are also aware of how certain factors can play a part in our involvement in the job. We have a good CRM programme in place that means should any crew member believe that the task doesn’t justify the risk, the task will be discontinued. For example, the doctor has a greater understanding of the medical reasons for the task and is best placed to advise whether or not the sortie is worth the increased risk of a low-flying HEMS mission in strong winds. ’ve been a HEMS pilot based in Cumbria for the past seven years, and each day comes with its own set of challenges. Contrary to what you might think, we experience a quieter time during the winter, as most of the 15 million annual visitors to the Lake District come during the summer months. Throughout this period, we’re dealing with novice walkers, climbers, paragliders and others who sometimes find themselves in remote locations needing urgent medical help. While our general work is slightly different to that of a commercial airline pilot, our training is equally as intensive and diverse. For example, all our pilots are trained/tested IFR, as per commercial pilots, but most HEMS pilots will have previous mountain flying experience of how to navigate and land in such terrain. But, being charity funded, we don’t get as much training in this environment as we would like. We also experience some issues in common with those in commercial aviation, such as fatigue. However, one specific issue that crops up is the self-induced pressure we can put ourselves under. Self-induced pressure can come from all the crew, but for different reasons. For example, if a crew member has a young family and the task is to a child, the perception of risk versus need can be skewed by the thought of “what if it was my child?”. This is where CAA/EASA regulations come in, to protect us from ourselves. Commercial aviation comes with commercial pressures to complete the sortie, HEMS comes with emotional pressures to get the job done. Good CRM training and self/crew discipline stops us taking undue risk for those heart-string pulling tasks. There are countless anecdotal tails of HEMS crews busting a gut to get to that life or death task, only for the patient to walk to the aircraft with an overnight bag packed. KNOWING THAT THE CHOICES WE MAKE CAN BE THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN LIFE AND DEATH BRINGS WITH IT ENORMOUS RESPONSIBILITY Being part of a HEMS operation brings other stresses as well, such as the fact that we’re charity-based and, therefore, there isn’t always operational joined up thinking between neighbouring charities, or NHS trusts and the local Air Ambulance charity. But this is constantly being worked on, so the most appropriate aircraft is sent to the task, even if it is in the neighbouring charity’s or NHS trust’s area. We share some other dangers with the commercial aviation sector, too – drones and lasers have become an increasing risk. The last thing we need is a laser attack on the way to the hospital. Add this to the long-standing mid-air collision risks with general aviation aircraft, and some days can bring with them a lot of different stressful factors. I have a growing concern over the lengthy and difficult process of reporting, and wonder if AIRPROX figures and such are lower than we see in reality, as a result. However, being a HEMS pilot can be incredibly rewarding. The self-induced stress does reduce with time and experience, but it’s important we maintain good CRM and continue to evaluate each situation as it arises. HEMS READ MORE “Talking helped considerably” KNOWING THAT THE CHOICES WE Log Board member Mike Buckley is a retired helicopter pilot. Here, he recounts his time as a HEMS pilot and reflects on the issues he faced during this time MAKE CAN BE THE DIFFERENCE At the December Log Board meeting, we discussed highlighting mental health and other personal issues to which many BETWEEN LIFE AND pilots find themselves subjected. I was asked if HEMS pilots subject themselves to more self-induced pressure. A good question – and one that made me reflect on my 18-month stint as a HEMS pilot. In the almost 17 years since I flew my final air ambulance mission, many things have changed: tighter regulations, a clearer understanding of role, and modern aircraft. The crewing has also evolved, with doctors now joining paramedics as crew members, increasing the effectiveness of many operations. Some constants are, of course, the weather, and the high standards of training for both pilots and medical crew. I remember my first few days at Blackpool in September 2000: “this is a vital job”, “lives depend on me”, “must get out there and fly”, and so on. My paramedics soon straightened me out. On my first call out, I ran to the aircraft – which was just 20m outside our office – and jumped in, ready to start. Then I waited until the first paramedic walked out to join me. Lesson one: do not run to the aircraft. Don’t dawdle, either, as rushing around can easily lead to falls or slips. So walk out, strap in and let the first paramedic cover the start. I was fortunate that, for my first weeks, we had good weather with no low cloud or poor visibility. This allowed me to get my head into the correct mindset for HEMS operations. The weather limits at the time were basically on a sliding scale – as the cloud base came down, visibility had to increase. That may seem strange at first, but, for example, it meant we could fly in heavy rain, which limited forward visibility, provided we could maintain 1,000ft agl or better. Like most pilots, I added a little extra safety margin during my initial few months, moving closer to the minima as I grew more comfortable with the aircraft and familiar with the operational area. Part of a team The key to flying HEMS/EMS is teamwork. While the pilot would ultimately make the final go/no go decision, the input from the medical team was always a vital element. On those occasions when the weather was an issue, information about the casualty could prove to be crucial. Was the incident in a remote location, which would mean we would be first on scene? How long would a land ambulance take to get there? If a land crew was already in attendance, were we needed to provide rapid transport to the nearest hospital? The possibility of adding another three casualties to the incident was always considered. So the decision-making process was fairly clear-cut, but there was always that one incident – perhaps when a small child was involved – when you felt that extra pressure. The decision was hard to make sometimes. During my time on HEMS operations, I did have some difficult choices to make – and, at the time, I think I made the right ones. As for flying when unfit, two paramedics were always on hand to give their opinions. It was always pointed out that the aircraft was just another form of ambulance and there were lots of others, albeit slower ones, available. I remember one morning, stepping out of the aircraft and twisting my ankle on the skid. Being driven to A&E to have my ankle checked out, wearing my flying coverall, was pretty embarrassing. Overall, I don’t think HEMS pilots put themselves under self-induced pressure. In fact, I believe a seasoned HEMS pilot would be more likely to feel more emotional after flying has finished, reflecting back on some of the incidents and sights he/she may have seen during the day, especially if children have been involved. I know I was on a few occasions, as were some of the medics. The key was always to talk about it directly after the mission or during the routine debrief at the end of the day – another vital part of the teamwork. CRM became second nature, and having an experienced paramedic talk about an incident helped considerably. We hear of people suffering from PTSD after being involved in traumatic incidents, and flying HEMS can seem like that sometimes. I am not aware of any of my former colleagues having any such issues, but then again, I could be wrong. I hope not. DEATH BRINGS WITH IT ENORMOUS RESPONSIBILITY