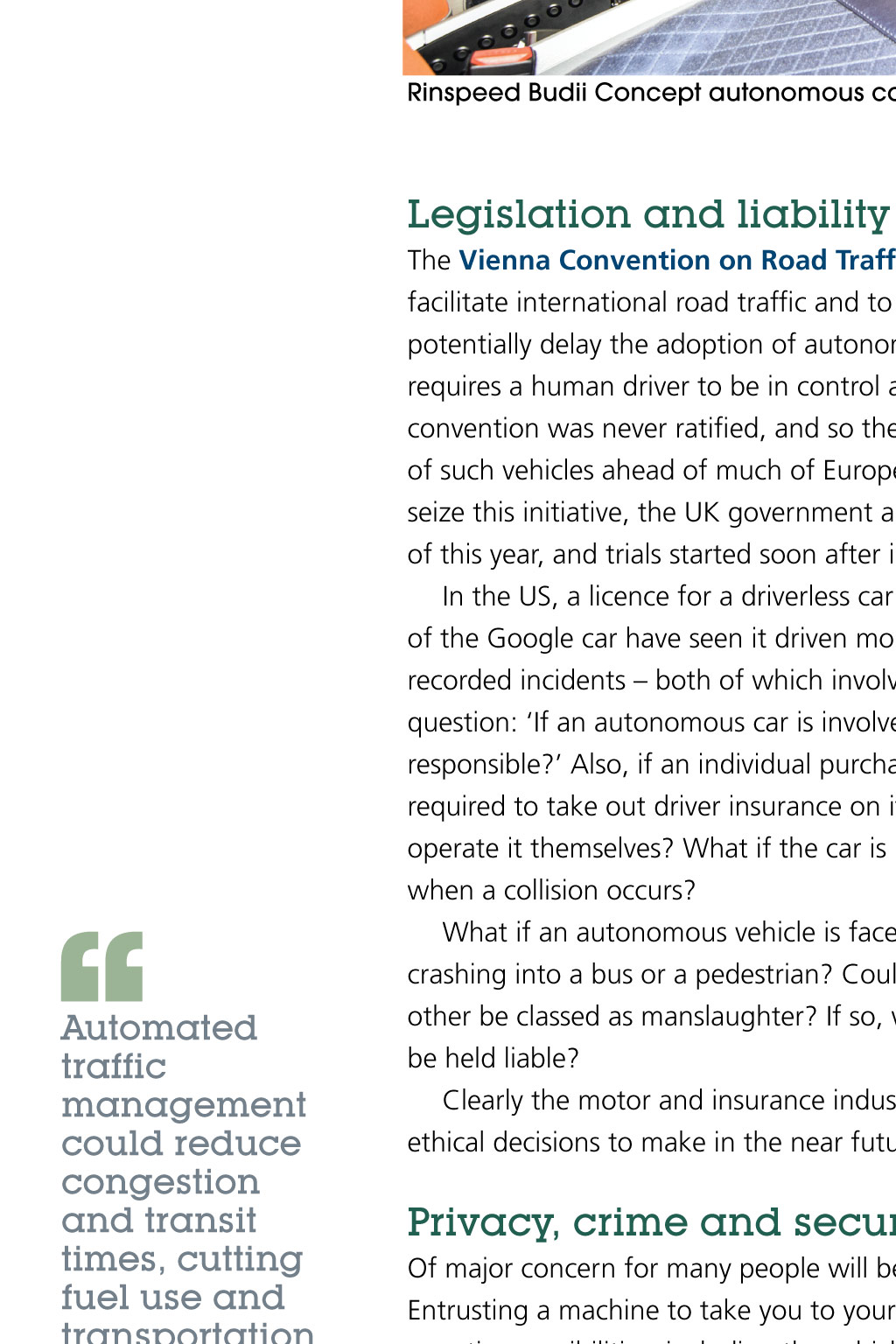

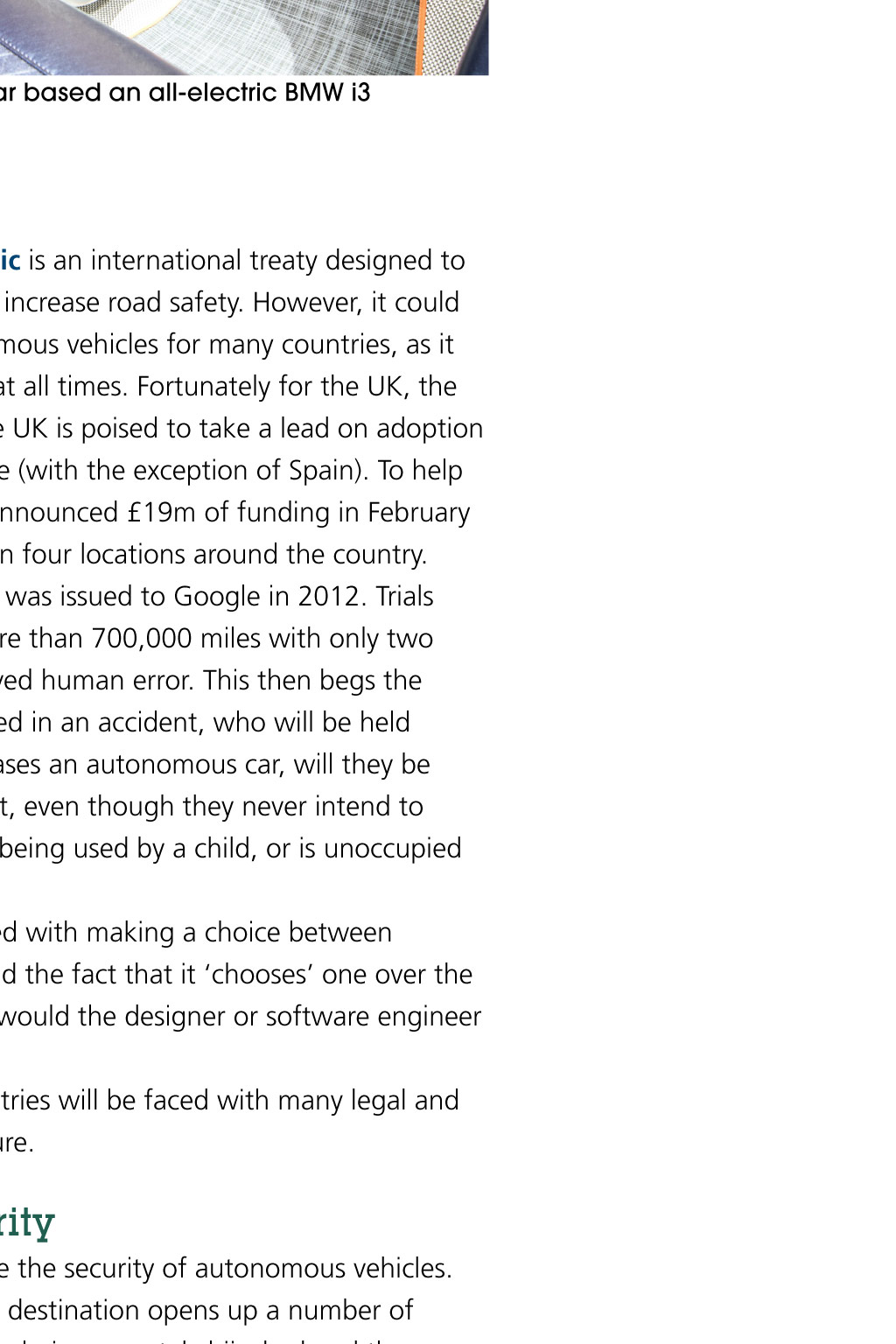

DRIVERLESS VEHICLES LIGHTSPRING / SHUTTERSTOCK ROAD WORRIER As countries around the world begin trials of driverless cars, Mark Turner CIRM investigates the potential and pitfalls of this new technology I n 1901, Gottlieb Daimler feared that the biggest risk limiting the growth of the motor industry would be the lack of qualified chauffeurs. Today this risk would appear to have been turned on its head, as soon every person could be chauffeured to their destination by a robotic machine. With a market estimated at 900bn in the next decade alone, the development of driverless vehicles will bring great reward to the motor industry and societies the world over but are we ready for the risks that attend it? An accident waiting to happen? It is estimated that more than 90 per cent of all accidents occuring on the roads today are caused by human error. Tiredness, texting, intoxication, passing distractions or simply sneezing are just a few of the reasons people can be unreliable behind the wheel. In the USA alone, more than 30,000 people a year die in automobile accidents, with a further 2.2m crashes resulting in serious injury. The cost to the countrys economy is estimated at US$300bn per year. Many people believe that removing drivers from the equation would alleviate significant suffering and devastation. Our modern machines are steadfast, accurate and unswerving in their ability to perform routine task for hours, days or years on end. As such, it is the goal of many researchers around the world to build autonomous vehicles that can drive from point A to point B with no input from the occupant. Indeed, a human may not even be on board. Such technology would not only significantly reduce the amount of death and destruction on the roads, but has other economic and social benefits as well. Automated traffic management could reduce congestion and transit times, cutting fuel use and transportation cost while benefiting the environment. Vehicles for the visually impaired, the elderly or children for whom driving today would be impossible could also become a reality. A grand challenge With the prospect of alleviating a great deal of human suffering and introducing so much economic potential, why havent automated vehicles become commercially available already? The simple answer is that driving is a very hard series of problems for machines to solve. The first truly autonomous vehicles capable of making independent decisions did not start to appear until the 1980s. However, the computing power of the time was unable to cope with the complexities of the constantly changing environment, and limitations in hardware made the vehicles susceptible to navigation errors. In order to speed up technological progress, in 2004 the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) instigated the DARPA Grand Challenge. This offered a US$1m prize to the team that could build a vehicle to navigate a 150-mile route successfully. In its first year, the furthest team achieved a measly seven miles, and so the prize fund was doubled for the following year. The second Grand Challenge saw five teams successfully complete the full 150mile route. Finally, the technology had developed sufficiently for the open road but what about the more complex challenge of driving in town? In 2007 DARPA instigated the third Grand Challenge, known as the Urban Challenge, with the construction of a 96-mile urban course around which the competing vehicles had to navigate autonomously while obeying all traffic regulations and coping with other moving vehicles. Six teams successfully completed the challenge. If an autonomous car is involved in an accident, who will be held responsible? Rinspeed Budii Concept autonomous car based an all-electric BMW i3 Legislation and liability Automated traffic management could reduce congestion and transit times, cutting fuel use and transportation cost while benefiting the environment The Vienna Convention on Road Traffic is an international treaty designed to facilitate international road traffic and to increase road safety. However, it could potentially delay the adoption of autonomous vehicles for many countries, as it requires a human driver to be in control at all times. Fortunately for the UK, the convention was never ratified, and so the UK is poised to take a lead on adoption of such vehicles ahead of much of Europe (with the exception of Spain). To help seize this initiative, the UK government announced 19m of funding in February of this year, and trials started soon after in four locations around the country. In the US, a licence for a driverless car was issued to Google in 2012. Trials of the Google car have seen it driven more than 700,000 miles with only two recorded incidents both of which involved human error. This then begs the question: If an autonomous car is involved in an accident, who will be held responsible? Also, if an individual purchases an autonomous car, will they be required to take out driver insurance on it, even though they never intend to operate it themselves? What if the car is being used by a child, or is unoccupied when a collision occurs? What if an autonomous vehicle is faced with making a choice between crashing into a bus or a pedestrian? Could the fact that it chooses one over the other be classed as manslaughter? If so, would the designer or software engineer be held liable? Clearly the motor and insurance industries will be faced with many legal and ethical decisions to make in the near future. Privacy, crime and security Of major concern for many people will be the security of autonomous vehicles. Entrusting a machine to take you to your destination opens up a number of negative possibilities, including the vehicle being remotely hijacked and the occupant being taken somewhere they do not want to go or, worse, being deliberately involved in an accident. On the flip side, a stolen car could simply be instructed to return home, or at least to report its current location and status. The idea of the criminal getaway car would quickly disappear if the police have the power to instruct the suspect vehicle to drive into a secure police compound. Another consideration for policy makers will be the resentment felt by many people that these vehicles are stealing jobs. It is my prediction that there will be an uncharacteristic increase in accidents involving automated vehicles as they are attacked by disgruntled people during the early adoption phase. This may also become a target for fraudulent insurance claims. Finally, the rights of privacy will need to be carefully considered as the vehicles will plan and most likely record every journey they make. It could make for some interesting testimony when a vehicle log is used as evidence in divorce proceedings. The end of the road? Without doubt these developments in autonomous vehicular technology will change society in the next few years, with as yet unpredictable social consequences. Fewer drivers mean we will not need such a large training, testing and licensing infrastructure. With law-abiding machines driving the roads, revenues from speed cameras will drop, leading to local authorities needing to fill the gap with other systems. When cars park themselves legally, traffic enforcement officers will become obsolete. The list goes on. And yet, the thrill of speed and freedom will still attract many people to learn the old skill of driving. I am confident that driving will not pass into history just yet. However, I look forward to the day that a driverless vehicle wins an F1 race against a human competitor. Mark Turner CIRM is enterprise risk manager (UK) at Selex ES