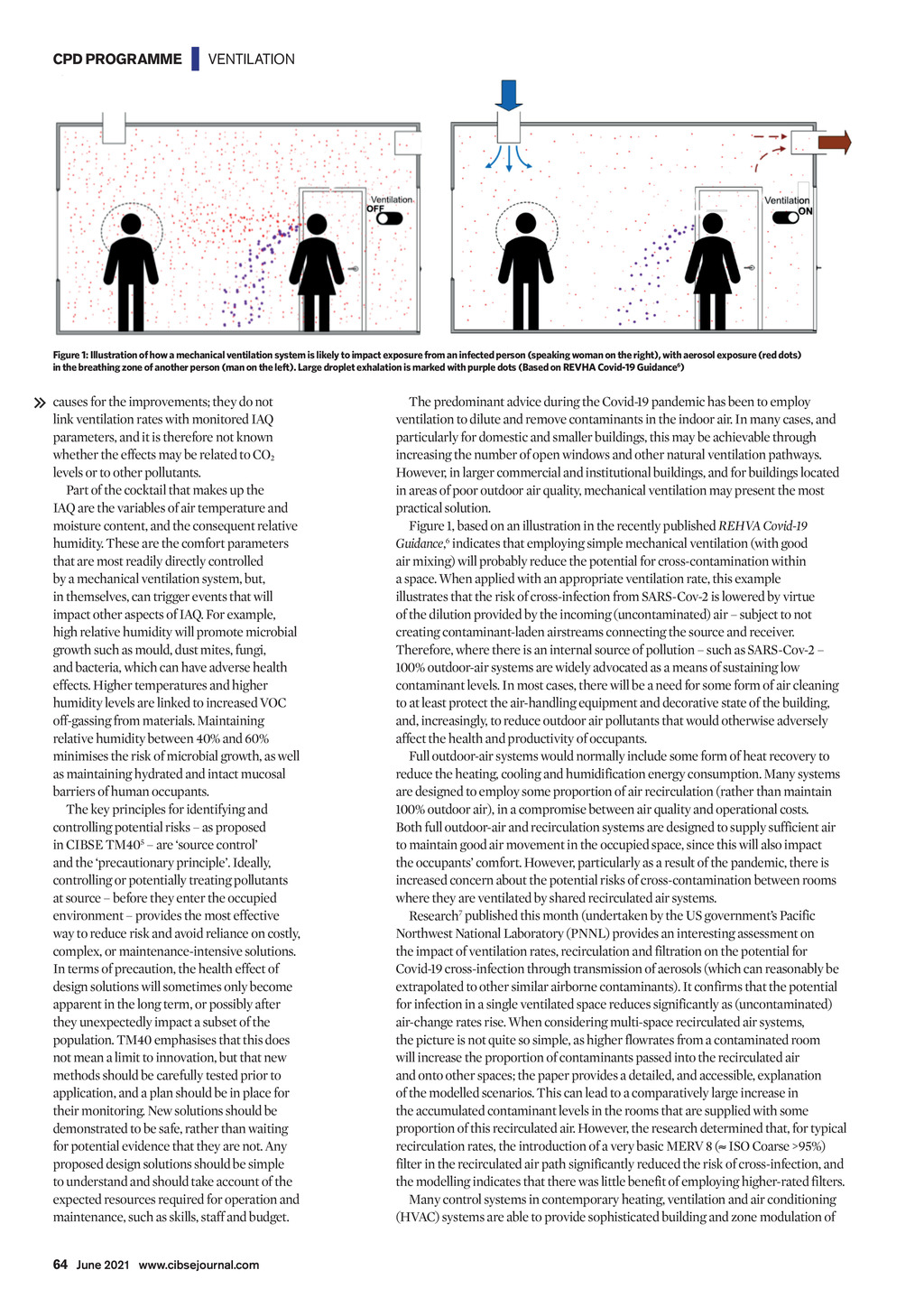

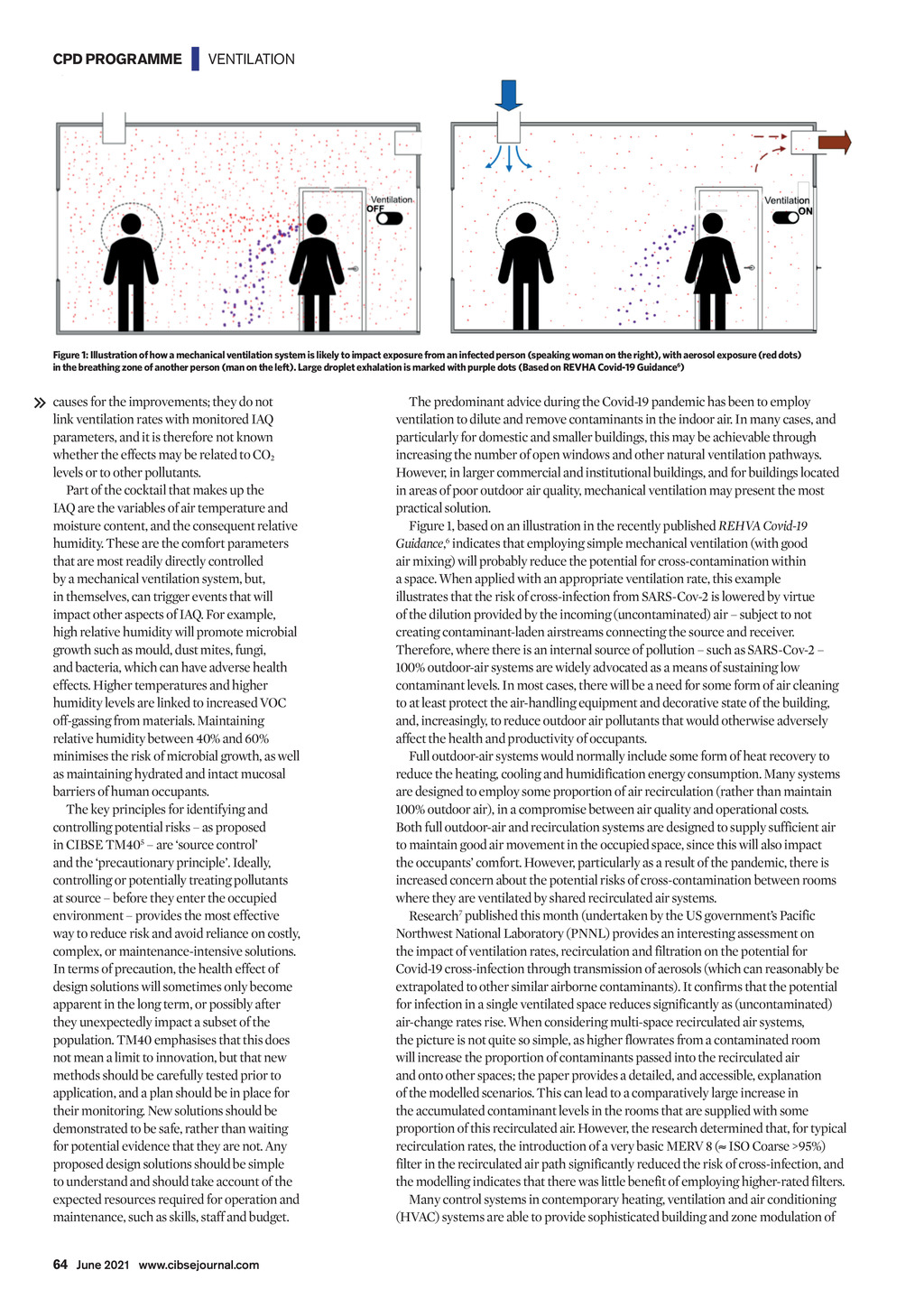

CPD PROGRAMME | VENTILATION Figure 1: Illustration of how a mechanical ventilation system is likely to impact exposure from an infected person (speaking woman on the right), with aerosol exposure (red dots) in the breathing zone of another person (man on the left). Large droplet exhalation is marked with purple dots (Based on REVHA Covid-19 Guidance6) causes for the improvements; they do not link ventilation rates with monitored IAQ parameters, and it is therefore not known whether the effects may be related to CO2 levels or to other pollutants. Part of the cocktail that makes up the IAQ are the variables of air temperature and moisture content, and the consequent relative humidity. These are the comfort parameters that are most readily directly controlled by a mechanical ventilation system, but, in themselves, can trigger events that will impact other aspects of IAQ. For example, high relative humidity will promote microbial growth such as mould, dust mites, fungi, and bacteria, which can have adverse health effects. Higher temperatures and higher humidity levels are linked to increased VOC off-gassing from materials. Maintaining relative humidity between 40% and 60% minimises the risk of microbial growth, as well as maintaining hydrated and intact mucosal barriers of human occupants. The key principles for identifying and controlling potential risks as proposed in CIBSE TM405 are source control and the precautionary principle. Ideally, controlling or potentially treating pollutants at source before they enter the occupied environment provides the most effective way to reduce risk and avoid reliance on costly, complex, or maintenance-intensive solutions. In terms of precaution, the health effect of design solutions will sometimes only become apparent in the long term, or possibly after they unexpectedly impact a subset of the population. TM40 emphasises that this does not mean a limit to innovation, but that new methods should be carefully tested prior to application, and a plan should be in place for their monitoring. New solutions should be demonstrated to be safe, rather than waiting for potential evidence that they are not. Any proposed design solutions should be simple to understand and should take account of the expected resources required for operation and maintenance, such as skills, staff and budget. The predominant advice during the Covid-19 pandemic has been to employ ventilation to dilute and remove contaminants in the indoor air. In many cases, and particularly for domestic and smaller buildings, this may be achievable through increasing the number of open windows and other natural ventilation pathways. However, in larger commercial and institutional buildings, and for buildings located in areas of poor outdoor air quality, mechanical ventilation may present the most practical solution. Figure 1, based on an illustration in the recently published REHVA Covid-19 Guidance,6 indicates that employing simple mechanical ventilation (with good air mixing) will probably reduce the potential for cross-contamination within a space. When applied with an appropriate ventilation rate, this example illustrates that the risk of cross-infection from SARS-Cov-2 is lowered by virtue of the dilution provided by the incoming (uncontaminated) air subject to not creating contaminant-laden airstreams connecting the source and receiver. Therefore, where there is an internal source of pollution such as SARS-Cov-2 100% outdoor-air systems are widely advocated as a means of sustaining low contaminant levels. In most cases, there will be a need for some form of air cleaning to at least protect the air-handling equipment and decorative state of the building, and, increasingly, to reduce outdoor air pollutants that would otherwise adversely affect the health and productivity of occupants. Full outdoor-air systems would normally include some form of heat recovery to reduce the heating, cooling and humidification energy consumption. Many systems are designed to employ some proportion of air recirculation (rather than maintain 100% outdoor air), in a compromise between air quality and operational costs. Both full outdoor-air and recirculation systems are designed to supply sufficient air to maintain good air movement in the occupied space, since this will also impact the occupants comfort. However, particularly as a result of the pandemic, there is increased concern about the potential risks of cross-contamination between rooms where they are ventilated by shared recirculated air systems. Research7 published this month (undertaken by the US governments Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) provides an interesting assessment on the impact of ventilation rates, recirculation and filtration on the potential for Covid-19 cross-infection through transmission of aerosols (which can reasonably be extrapolated to other similar airborne contaminants). It confirms that the potential for infection in a single ventilated space reduces significantly as (uncontaminated) air-change rates rise. When considering multi-space recirculated air systems, the picture is not quite so simple, as higher flowrates from a contaminated room will increase the proportion of contaminants passed into the recirculated air and onto other spaces; the paper provides a detailed, and accessible, explanation of the modelled scenarios. This can lead to a comparatively large increase in the accumulated contaminant levels in the rooms that are supplied with some proportion of this recirculated air. However, the research determined that, for typical recirculation rates, the introduction of a very basic MERV 8 ( ISO Coarse >95%) filter in the recirculated air path significantly reduced the risk of cross-infection, and the modelling indicates that there was little benefit of employing higher-rated filters. Many control systems in contemporary heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) systems are able to provide sophisticated building and zone modulation of 64 June 2021 www.cibsejournal.com CIBSE June 21 pp63-66 CPD 180.indd 64 21/05/2021 16:31