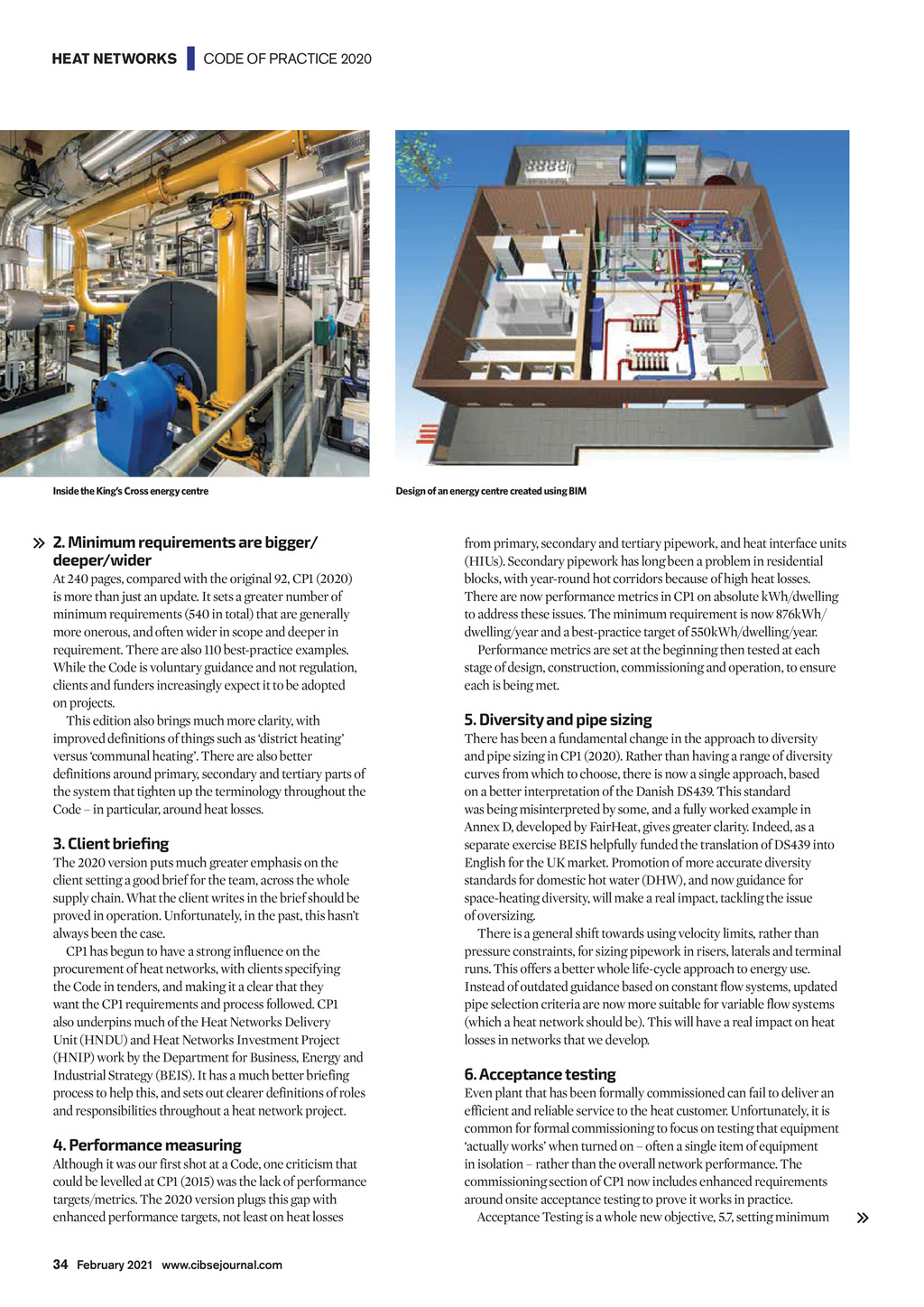

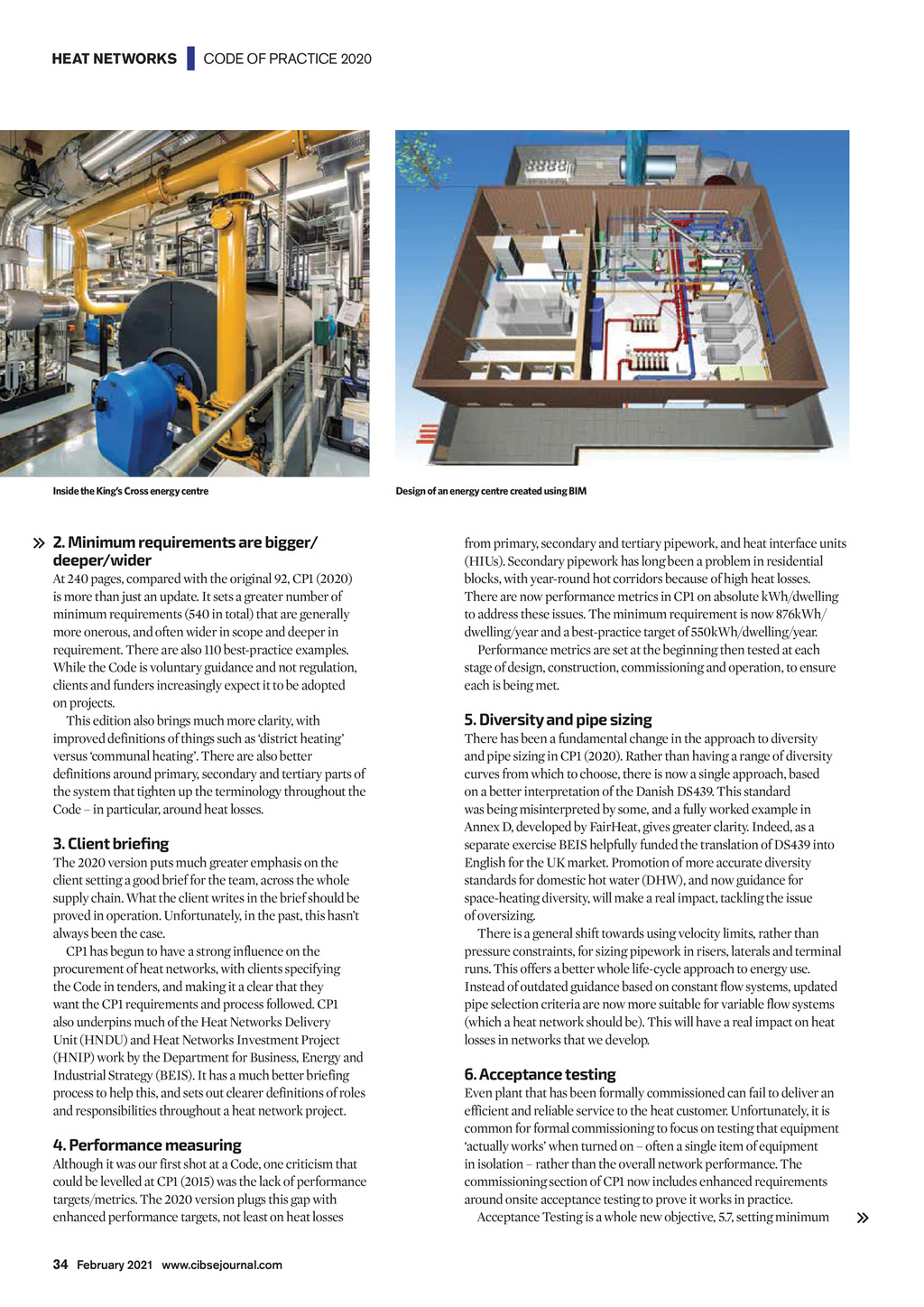

HEAT NETWORKS | CODE OF PRACTICE 2020 Inside the Kings Cross energy centre 2. Minimum requirements are bigger/ deeper/wider At 240 pages, compared with the original 92, CP1 (2020) is more than just an update. It sets a greater number of minimum requirements (540 in total) that are generally more onerous, and often wider in scope and deeper in requirement. There are also 110 best-practice examples. While the Code is voluntary guidance and not regulation, clients and funders increasingly expect it to be adopted on projects. This edition also brings much more clarity, with improved definitions of things such as district heating versus communal heating. There are also better definitions around primary, secondary and tertiary parts of the system that tighten up the terminology throughout the Code in particular, around heat losses. 3. Client briefing The 2020 version puts much greater emphasis on the client setting a good brief for the team, across the whole supply chain. What the client writes in the brief should be proved in operation. Unfortunately, in the past, this hasnt always been the case. CP1 has begun to have a strong influence on the procurement of heat networks, with clients specifying the Code in tenders, and making it a clear that they want the CP1 requirements and process followed. CP1 also underpins much of the Heat Networks Delivery Unit (HNDU) and Heat Networks Investment Project (HNIP) work by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS). It has a much better briefing process to help this, and sets out clearer definitions of roles and responsibilities throughout a heat network project. 4. Performance measuring Although it was our first shot at a Code, one criticism that could be levelled at CP1 (2015) was the lack of performance targets/metrics. The 2020 version plugs this gap with enhanced performance targets, not least on heat losses Design of an energy centre created using BIM from primary, secondary and tertiary pipework, and heat interface units (HIUs). Secondary pipework has long been a problem in residential blocks, with year-round hot corridors because of high heat losses. There are now performance metrics in CP1 on absolute kWh/dwelling to address these issues. The minimum requirement is now 876kWh/ dwelling/year and a best-practice target of 550kWh/dwelling/year. Performance metrics are set at the beginning then tested at each stage of design, construction, commissioning and operation, to ensure each is being met. 5. Diversity and pipe sizing There has been a fundamental change in the approach to diversity and pipe sizing in CP1 (2020). Rather than having a range of diversity curves from which to choose, there is now a single approach, based on a better interpretation of the Danish DS439. This standard was being misinterpreted by some, and a fully worked example in Annex D, developed by FairHeat, gives greater clarity. Indeed, as a separate exercise BEIS helpfully funded the translation of DS439 into English for the UK market. Promotion of more accurate diversity standards for domestic hot water (DHW), and now guidance for space-heating diversity, will make a real impact, tackling the issue of oversizing. There is a general shift towards using velocity limits, rather than pressure constraints, for sizing pipework in risers, laterals and terminal runs. This offers a better whole life-cycle approach to energy use. Instead of outdated guidance based on constant flow systems, updated pipe selection criteria are now more suitable for variable flow systems (which a heat network should be). This will have a real impact on heat losses in networks that we develop. 6. Acceptance testing Even plant that has been formally commissioned can fail to deliver an efficient and reliable service to the heat customer. Unfortunately, it is common for formal commissioning to focus on testing that equipment actually works when turned on often a single item of equipment in isolation rather than the overall network performance. The commissioning section of CP1 now includes enhanced requirements around onsite acceptance testing to prove it works in practice. Acceptance Testing is a whole new objective, 5.7, setting minimum 34 February 2021 www.cibsejournal.com CIBSE Feb21 pp33-34, 36-37 CP1 Heat Newtork Code.indd 34 22/01/2021 15:45