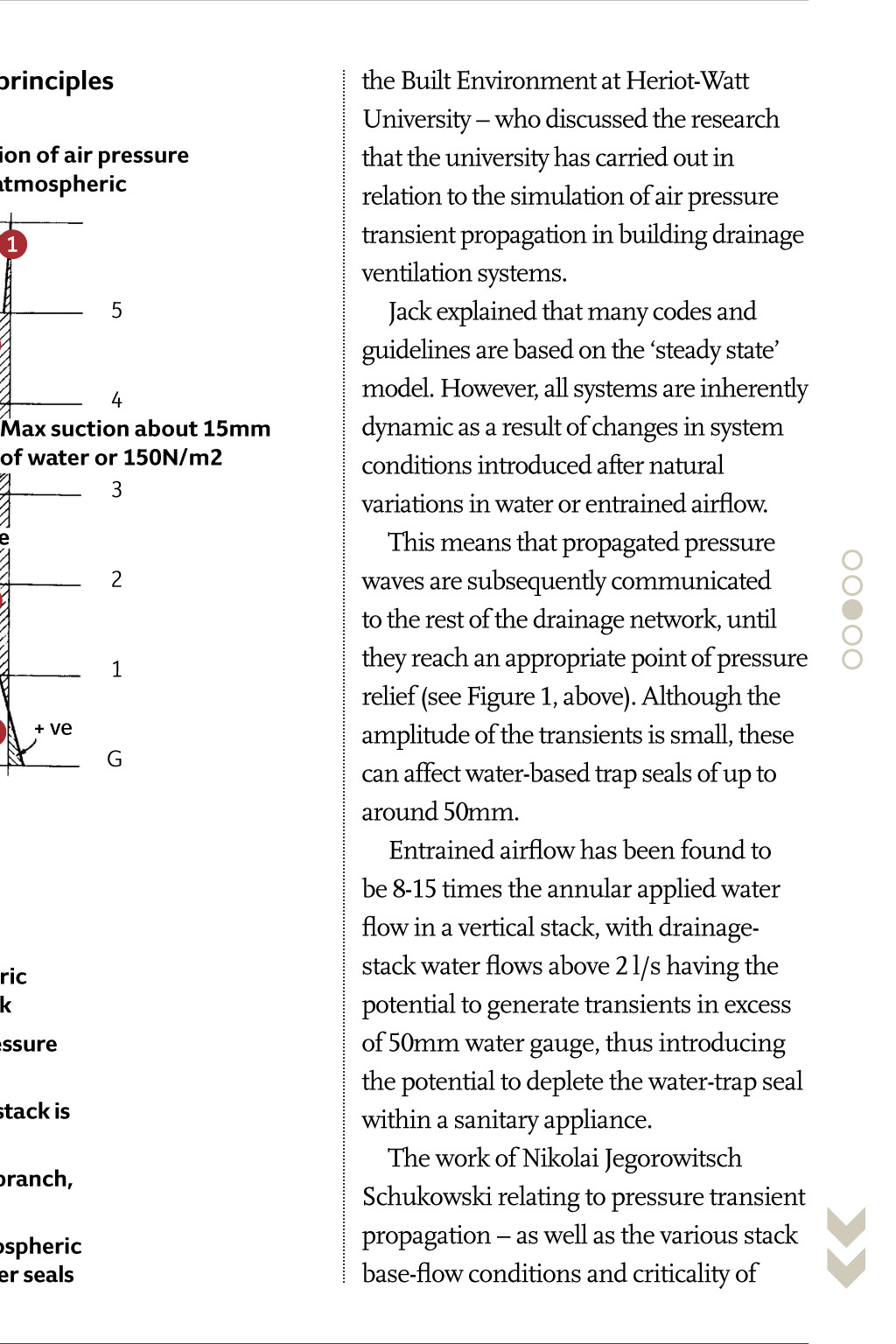

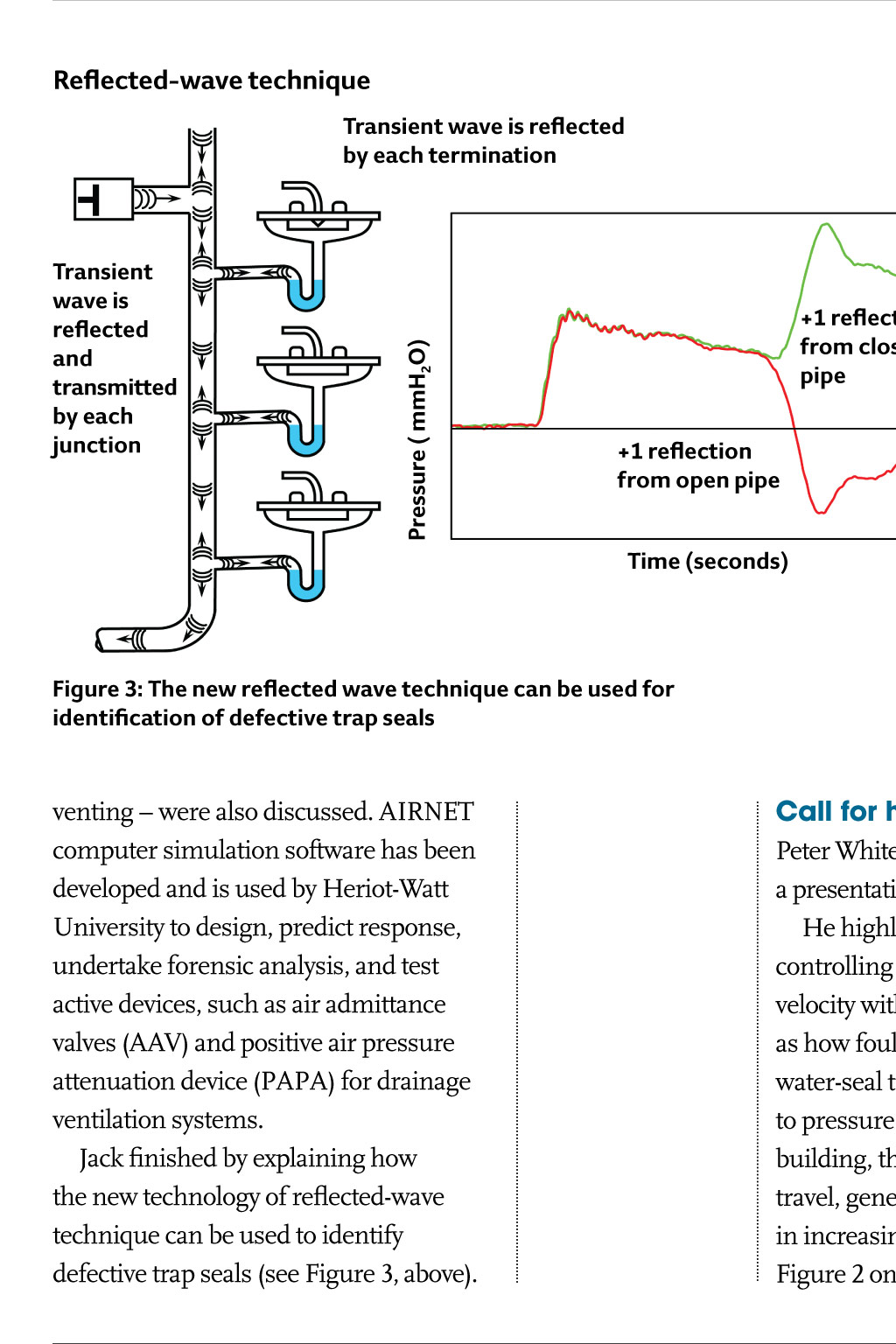

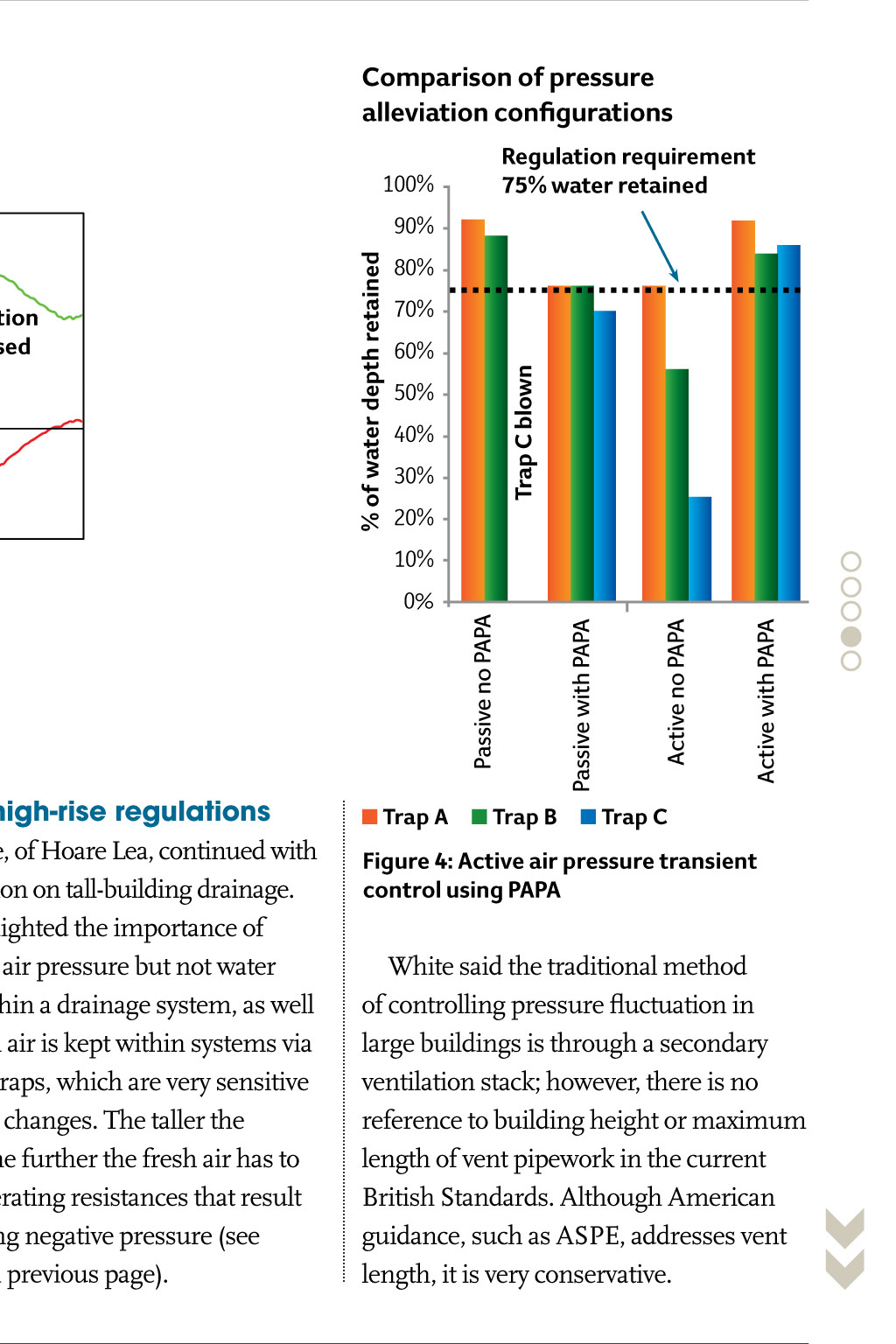

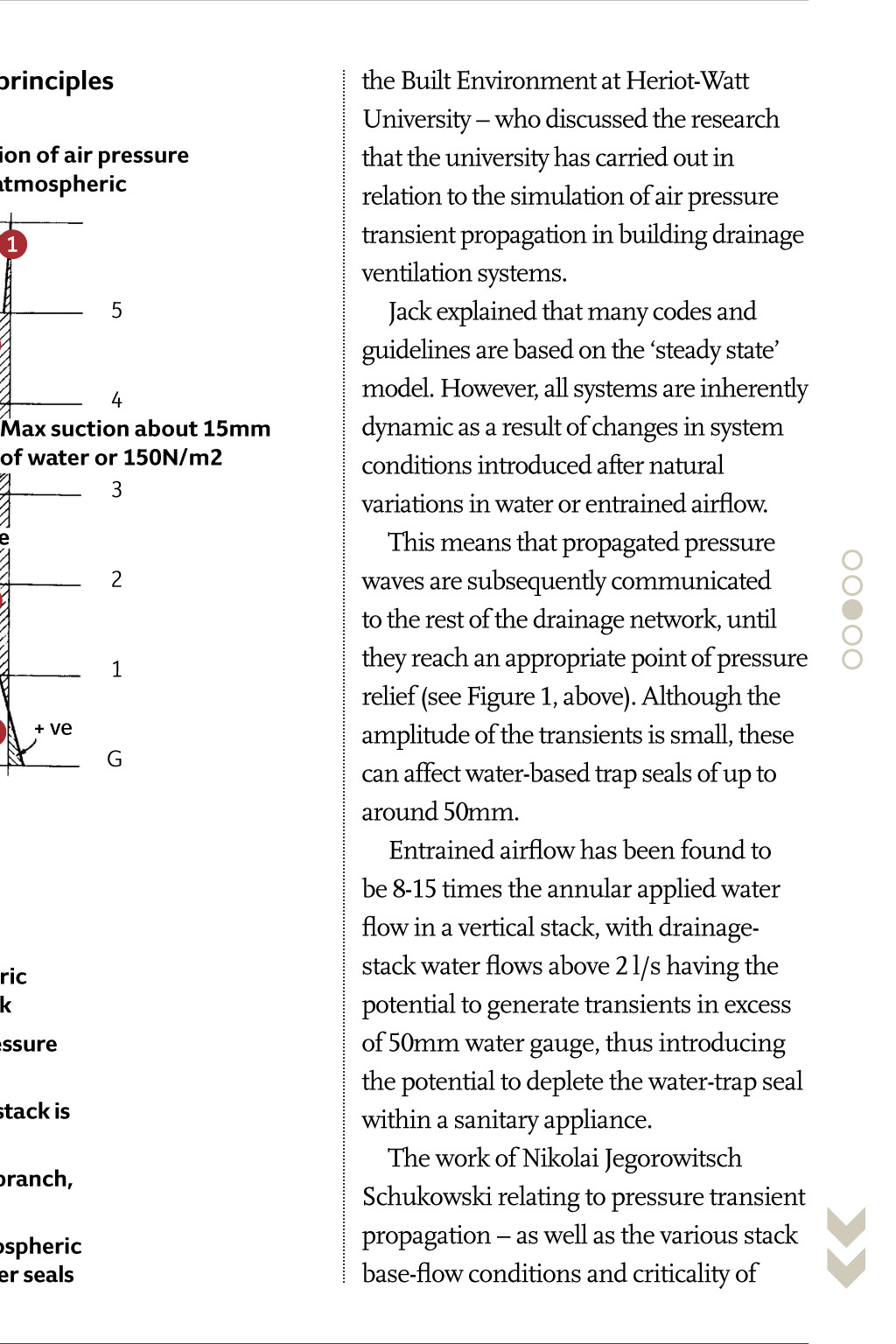

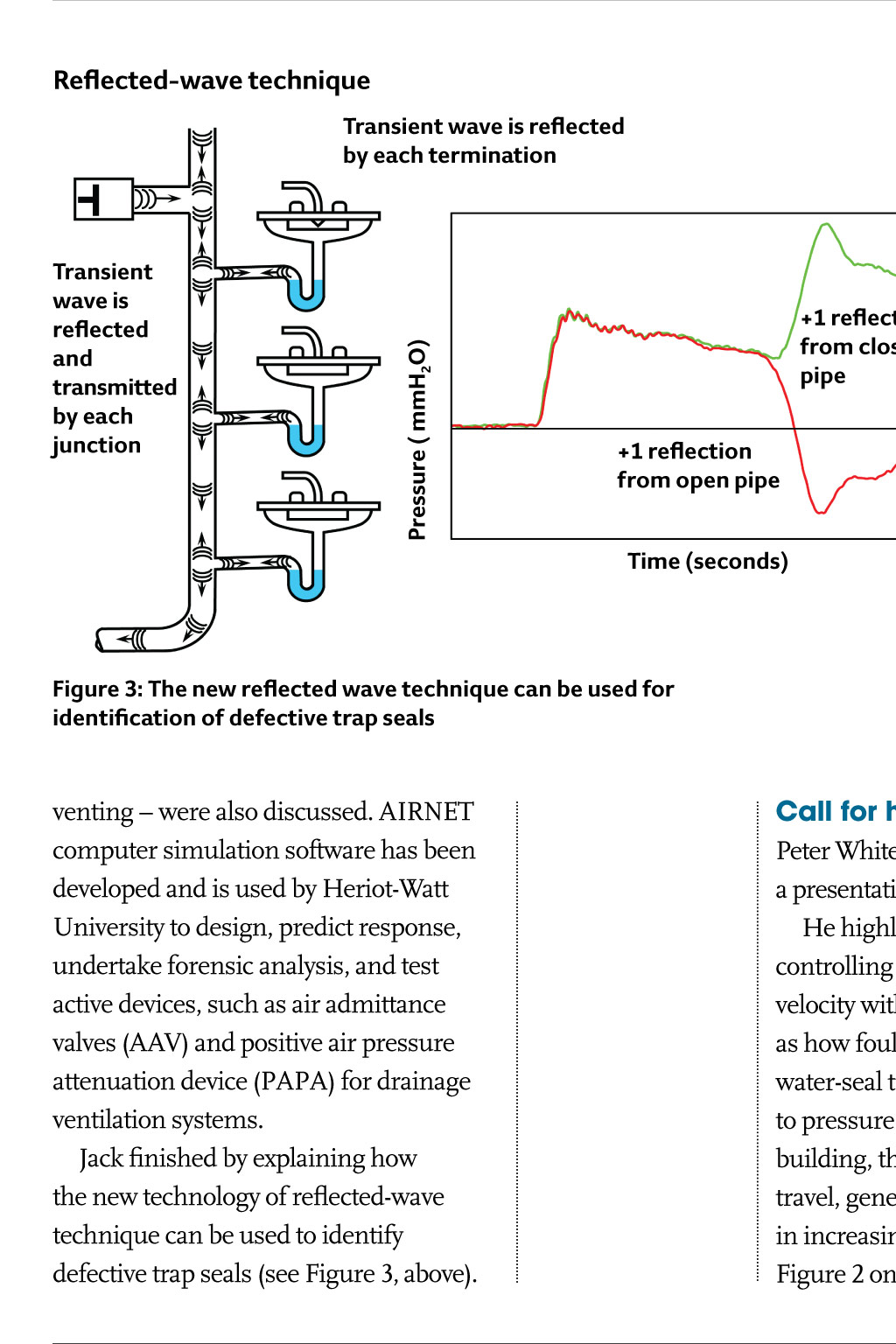

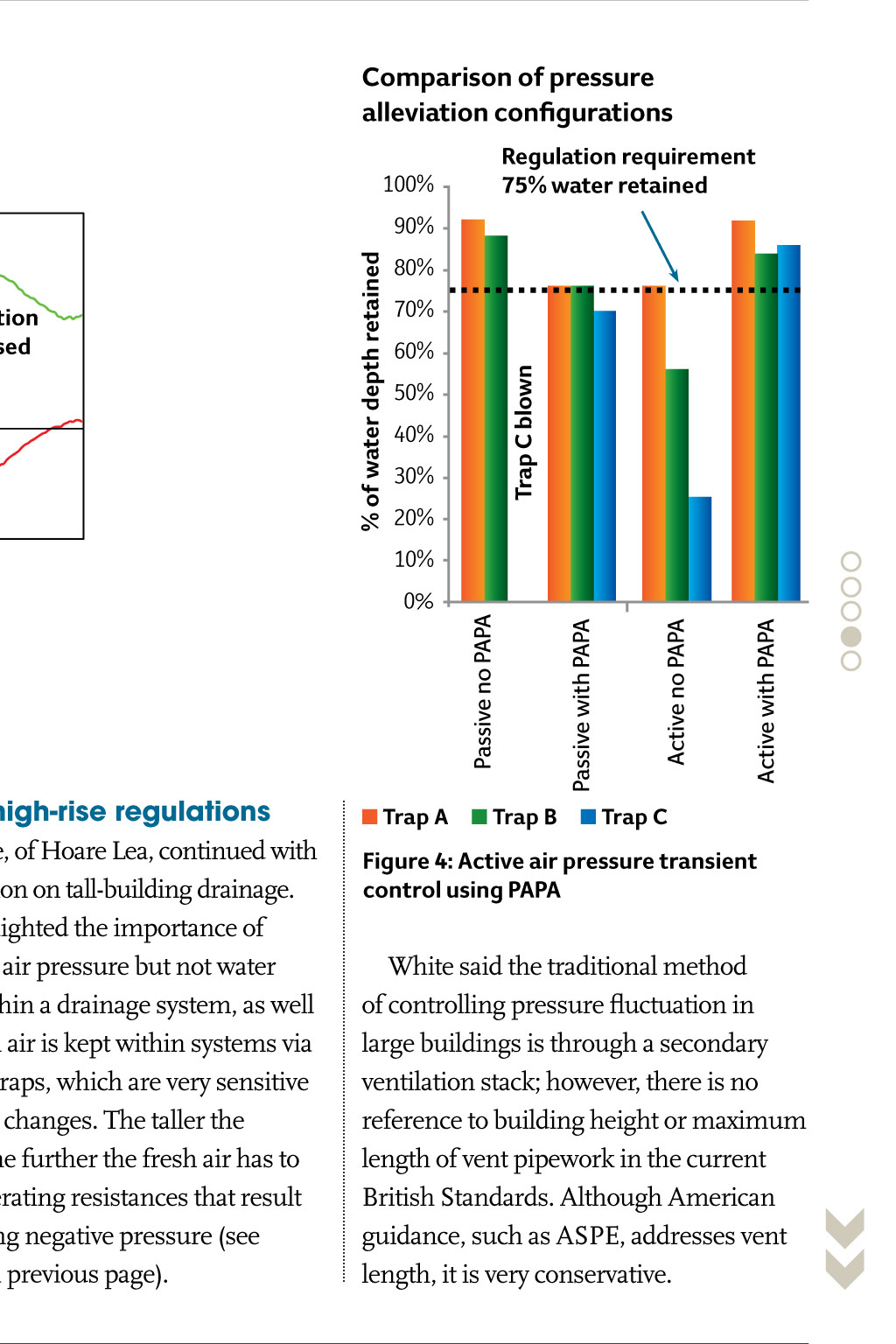

Drainage SOPHE Conference Noise control in drainage systems especially in highrise buildings is a challenge for engineers. Steve Vaughan reports from the Building Drainage Conference to hear experts discussing this topic and others, including fire breakout prevention and ventilation and airflow in complex drainage systems A FluShhh opened with manufacturers of cast iron, stainless steel and plastic drainage pipework presenting on the characteristics for each material, and the acoustic control methods that can be adopted. For all materials, airborne and structure-borne noise requires careful consideration. Quite often, manufacturers claims are based on selective information such as differing flow rates so comparisons may be difficult to evaluate. BS EN 14366:2004 aims to provide comparable data, so that an informed choice can be made between pipework materials. However, specifiers often demand more comprehensive tests that relate to drainage offsets and horizontal runs, as well as more applicable installation scenarios, including concealed pipework, turbulent flow (standard tests with laminar flow), water fill, and systems with appliance branch connections. These are more appropriate to specific site constraints, which BS EN 14366:2004 does not consider. Comparisons were made between the Building Regulations Approved Document E (Resistance to the passage of sound), BS 8233:1999 (Guidance on sound insulation and noise reduction for buildings) and European DIN 4109 PlUmbing For HealtH A one-day conference by the Royal Society for Public Health will be held on 11 March at its Portland Place HQ, in London, followed by the Worshipful Company of Plumbers annual lecture Pressure transient propagation Air movement due to no-slip Relief point for transient Trap affected by transient No-slip interface Annular flow Change in discharge flow rate communicated as an air pressure transient Air core Figure 1 Tall-building drainage designprinciples Variation of air pressure from atmospheric Induce airflow WC inlet discharging 5 5 4 Basin inlet discharging 3 Sink inlet discharging 4 Max suction about 15mm of water or 150N/m2 3 - ve 2 Thickness of water sheet about 4mm 2 1 Airflow 1 + ve Water depth about 45mm G G The drainage venting design for the 48-storey Pan Peninsula in London was based on BS12056 and ASPE guidance Figure 2 The taller the building, the further the fresh air has to travel, generating resistances that result in increasing negative pressure Pressure falls below atmospheric immediately below top of stack Friction increases negative pressure down stack Pressure drops further where stack is restricted by branch flows Below the lowest discharging branch, pressure gradually increases Pressure increases above atmospheric at base and can blow out water seals irflow and noise prevention were dominant themes at the CIBSE Society of Public Health Engineers (SoPHE) Building Drainage Conference on 15 January. Noise, fire breakout, pathogens and hygienic drainage design, as well as airflow in drainage systems particularly in high-rise buildings were all covered by specialists at the event, held for the first time at the Kohn Centre, at The Royal Society in London. The first session on noise breakout in above-ground drainage systems (Sound insulation in buildings), with manufacturers explaining how they carried out independent testing to evaluate their systems against these standards. Whichever drainage pipework material is chosen, the fixing and support methods together with the installation quality, room layouts and riser or ceiling-void construction play an important part in limiting the acoustic impact of the building drainage system on the internal environment. Walter van der Schee, who represents the TVVL an association for building service technology in Holland explained that many factors influence the level of noise production and noise reduction in drainage systems. He said TVVL carries out independent testing using purposemade test rigs and apparatus that mimics real-life installations. Van der Schee went on to discuss how ceiling construction, light fittings and other ceiling penetrations can all influence the acoustic performance, while pipework bends and offsets can impact on noise generated by waste-water flow. dynamic models Session two, on airflow in above-ground drainage, started with Professor Lynne Jack deputy head of the School of the Built Environment at Heriot-Watt University who discussed the research that the university has carried out in relation to the simulation of air pressure transient propagation in building drainage ventilation systems. Jack explained that many codes and guidelines are based on the steady state model. However, all systems are inherently dynamic as a result of changes in system conditions introduced after natural variations in water or entrained airflow. This means that propagated pressure waves are subsequently communicated to the rest of the drainage network, until they reach an appropriate point of pressure relief (see Figure 1, above). Although the amplitude of the transients is small, these can affect water-based trap seals of up to around 50mm. Entrained airflow has been found to be 8-15 times the annular applied water flow in a vertical stack, with drainagestack water flows above 2 l/s having the potential to generate transients in excess of 50mm water gauge, thus introducing the potential to deplete the water-trap seal within a sanitary appliance. The work of Nikolai Jegorowitsch Schukowski relating to pressure transient propagation as well as the various stack base-flow conditions and criticality of Reflected-wave technique Transient wave is reflected and transmitted by each junction Pressure ( mmH2O) Transient wave is reflected by each termination +1 reflection from closed pipe +1 reflection from open pipe Time (seconds) Figure 5: This floor gully has rounded component features, generated using advanced, deep-drawn metal coldforming techniques Figure 3: The new reflected wave technique can be used for identification of defective trap seals venting were also discussed. AIRNET computer simulation software has been developed and is used by Heriot-Watt University to design, predict response, undertake forensic analysis, and test active devices, such as air admittance valves (AAV) and positive air pressure attenuation device (PAPA) for drainage ventilation systems. Jack finished by explaining how the new technology of reflected-wave technique can be used to identify defective trap seals (see Figure 3, above). call for high-rise regulations Peter White, of Hoare Lea, continued with a presentation on tall-building drainage. He highlighted the importance of controlling air pressure but not water velocity within a drainage system, as well as how foul air is kept within systems via water-seal traps, which are very sensitive to pressure changes. The taller the building, the further the fresh air has to travel, generating resistances that result in increasing negative pressure (see Figure 2 on previous page). White said the traditional method of controlling pressure fluctuation in large buildings is through a secondary ventilation stack; however, there is no reference to building height or maximum length of vent pipework in the current British Standards. Although American guidance, such as ASPE, addresses vent length, it is very conservative. White added that the AIRNET software was used to verify the drainage venting design for Londons 48-storey Pan Peninsula building, which was based on a hybrid design using BS12056 and ASPE guidance. He highlighted the need for a UK guidance document relating to highrise drainage design. Comparison of pressure alleviation configurations provided a detailed insight into hygienic drainage design and pathogen avoidance. There was a brief overview of regulations, terminology and drainage functions for commercial kitchens and food preparation areas, as well as an explanation of the principal bacteria and pathogens found in food production areas. Good drainage design plays an important part in minimising bacteria and pathogen traps, and Jennings gave examples of both good and bad manufacture and design (see Figure 5 on previous page). Statistical data on foodborne disease was also reviewed, indicating that Campylobacter (3m long, or 33 times smaller than the width of a human hair) is by far the most common pathogen source of food contamination in the UK. In view of its size, it is obvious how poor drainage design and installation can have a significant impact on maintaining a hygienic environment. Chris Northey, SoPHE chair, thanked everyone, including sponsors Studor, Saint-Gobain, ACO Drainage, Blcher, Geberit, and Polypipe. cJ Regulation requirement 75% water retained 100% 80% 70% Trap C blown 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% Trap A Trap B Active with PAPA Active no PAPA 0% Passive with PAPA 10% Passive no PAPA System ventilation Steven White, from Studor, discussed the principles of active drainage ventilation. He introduced the history of automatic air admittance valves (AAVs) and how the trap seal a barrier between the drainage system and the living space can be depleted by many events, such as induced siphonage, self-siphonage, thermal depletion and wind effect. White showed various applications of AAVs, and explained how these can reduce roof penetrations and the amount of vent piping required. He also discussed their ability to balance the pressures in the drainage system. He explained active air pressure transient control using PAPA in conjunction with AAVs, and presented case studies of various drainage system arrangements. This, he said, could result in a system responding faster to air pressure changes, and be helpful over traditionally-designed systems (Figure 4). For the third session, the pipeline makers returned to discuss prevention of fire with details on the characteristics % of water depth retained 90% Trap C Figure 4: Active air pressure transient control using PAPA eor Rmade PlUmbing For HealtH and construction requirements for each material. Part B of the Building Regulations (2007) (B1 dwellings, B2 other than dwellings), was referenced, as well as HTM 05-02 (2013) and BB100 (2007), with examples of providing compliance noted by each presenter. In the closing presentation by Peter Jennings, of ACO Building Drainage, STEVE VAUGHAN is public health engineering regional director at Aecom, and sits on the CIBSE SoPHE technical committee