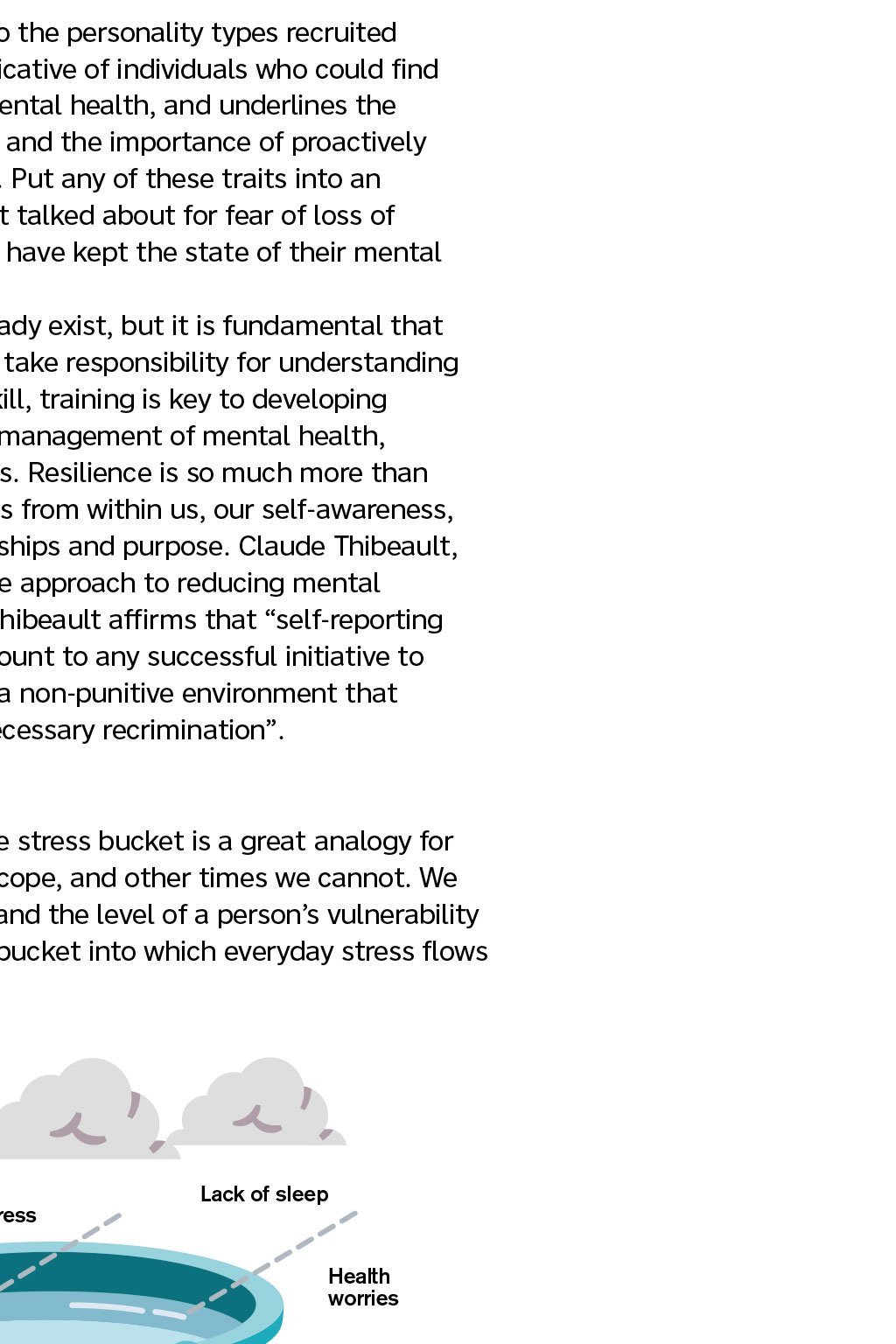

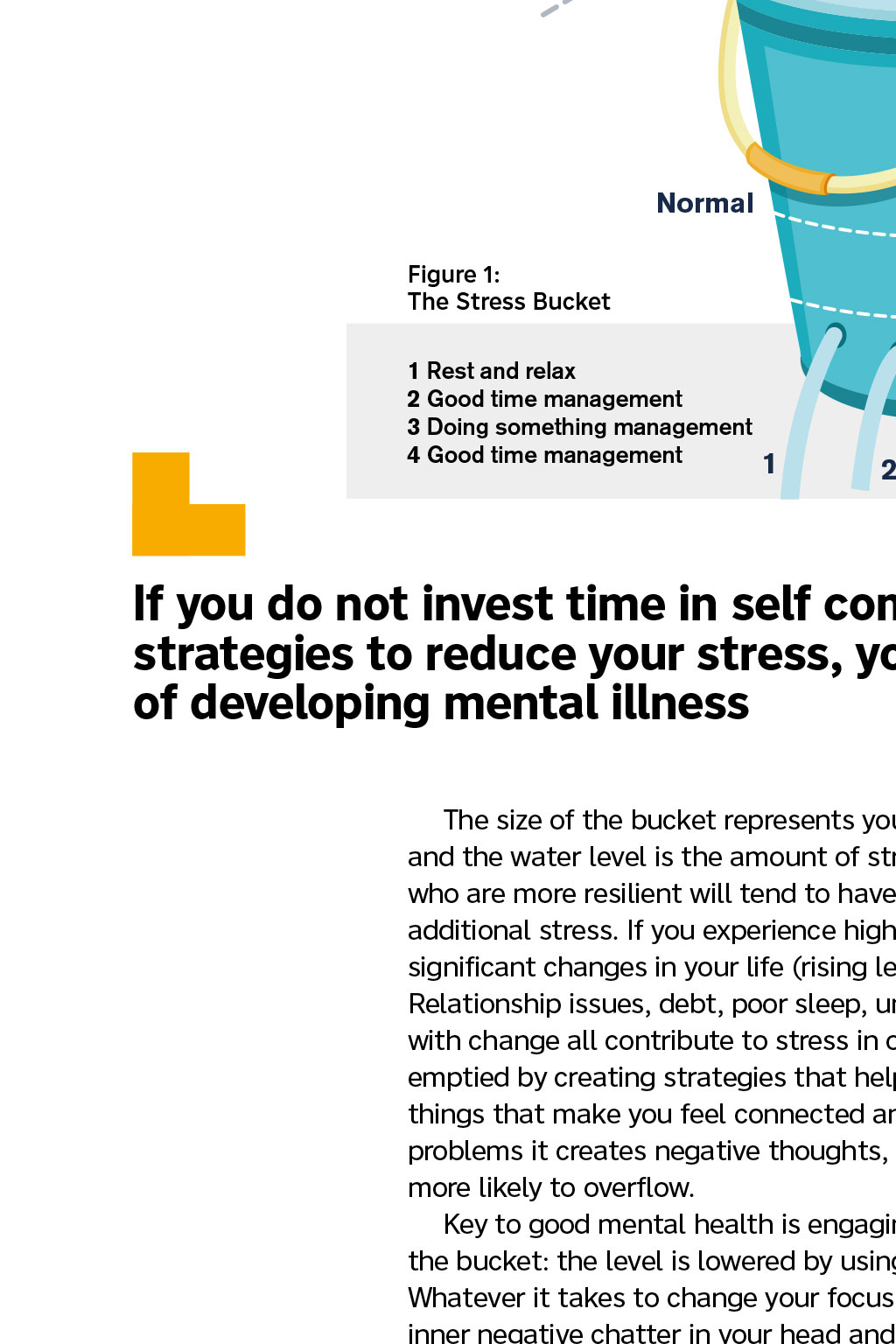

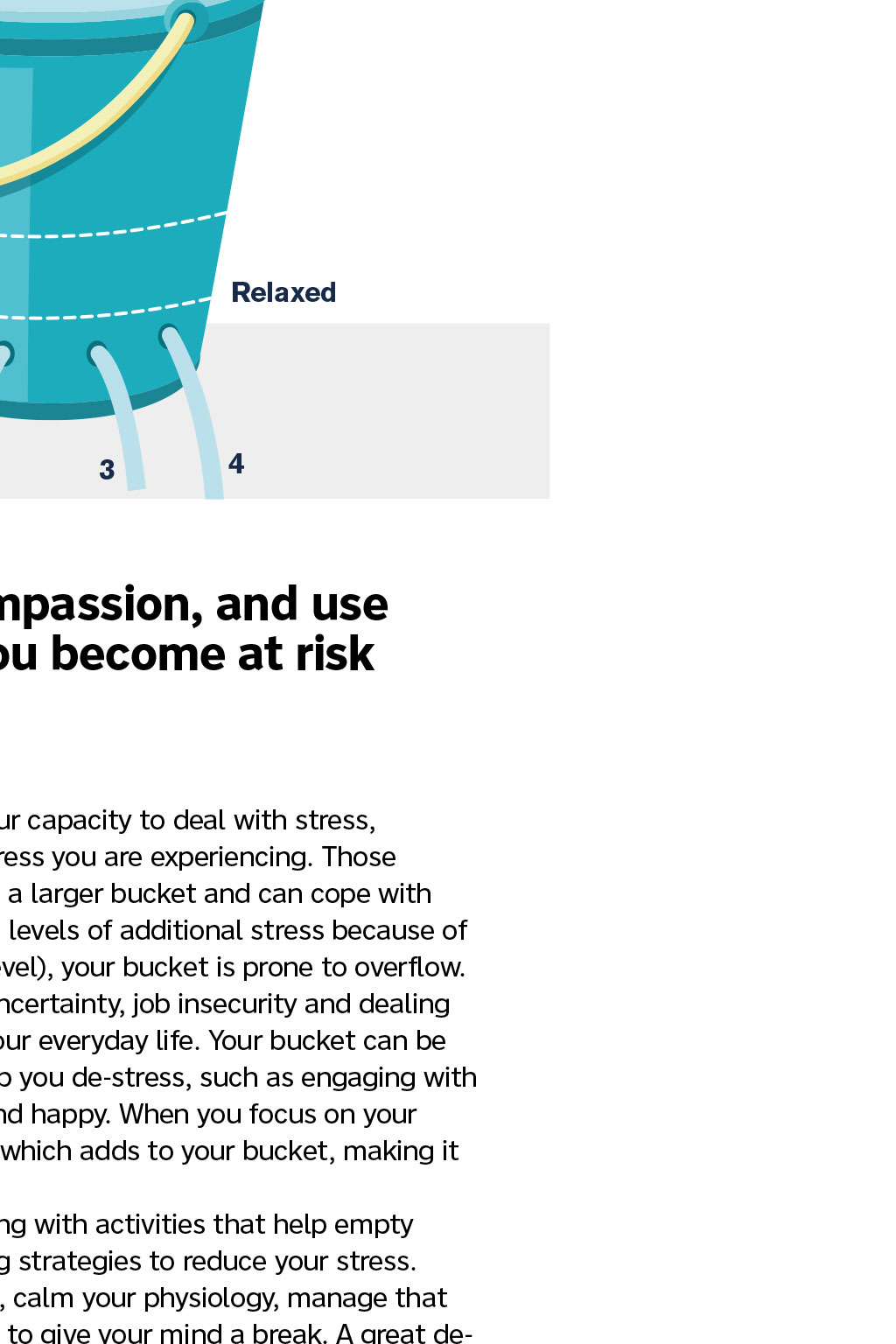

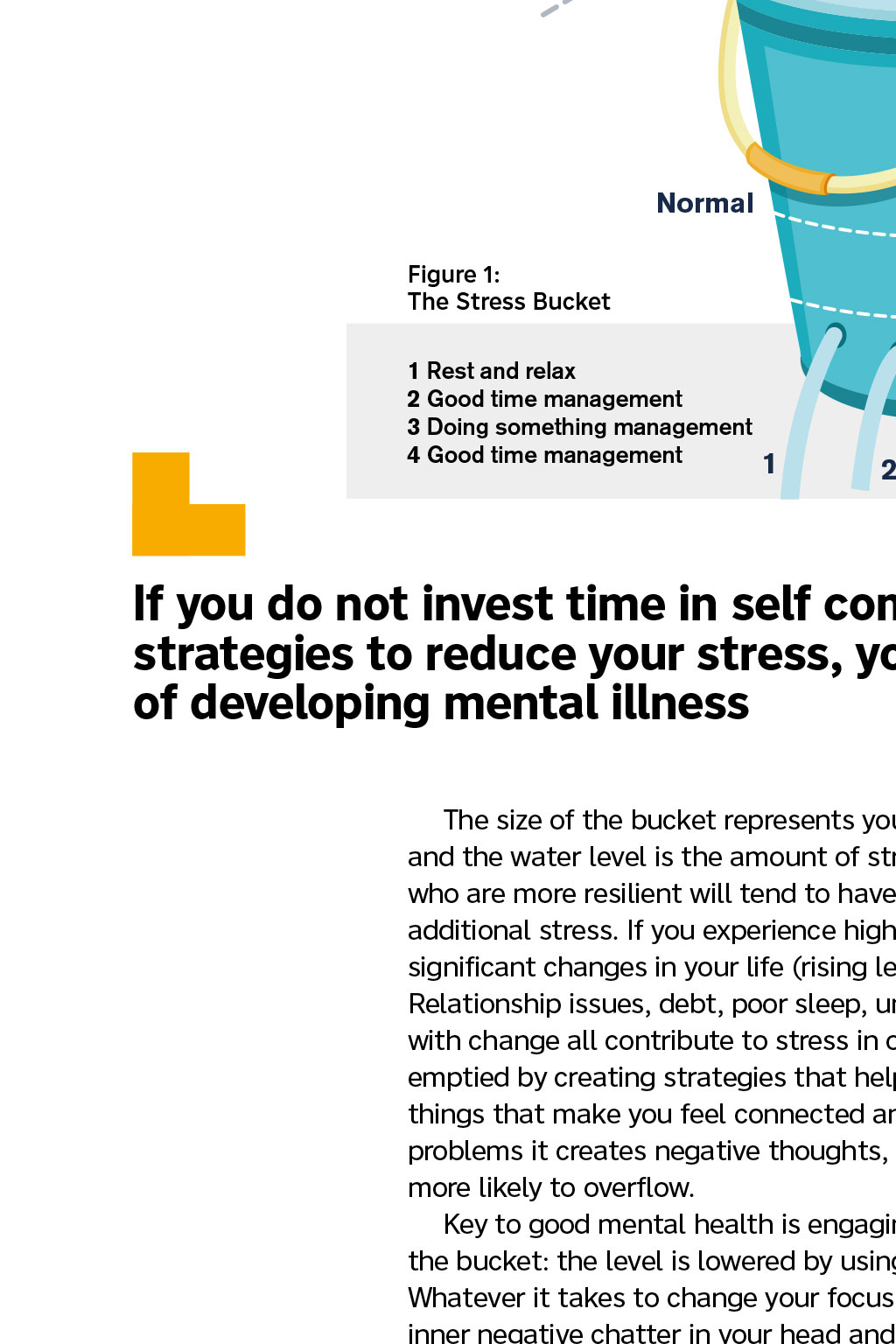

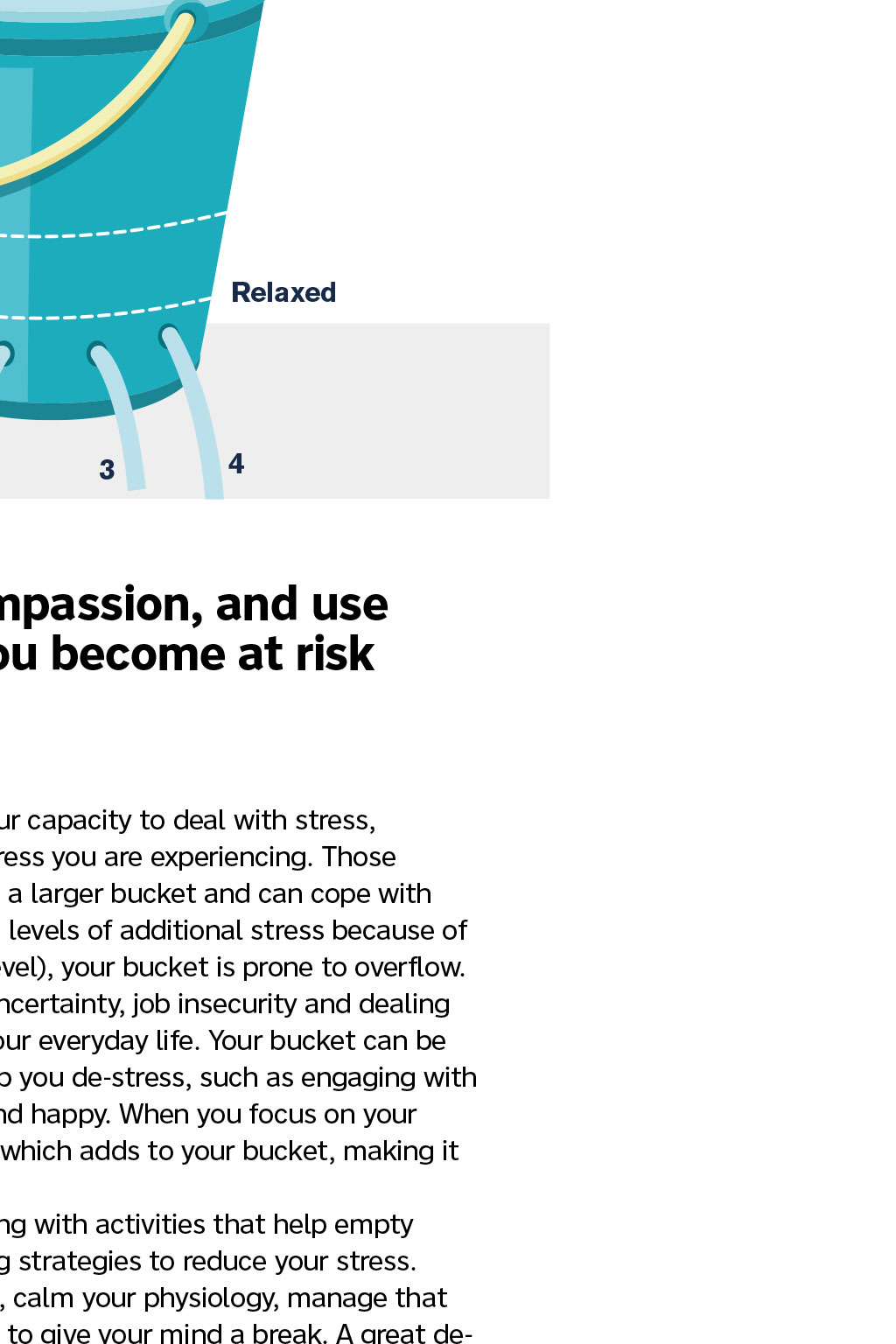

By Louise Pode, resilience and stress management consultant Over the summer, there has been an overall reduction in flying because of COVID-19, job insecurity, redundancy programmes, and the chaos of uncertain times – and it has raised awareness around mental health issues. But what is really being done about it in the aviation sector? Mental health and aviation have historically had an uncomfortable relationship. The JetBlue incident of 2012 and the tragic 2015 Germanwings accident raised the profile of mental health and took it to the top of the agenda. Some progress has been made, but there is still much to do. There are plenty of factors that indicate a significant number of pilots are experiencing a deterioration in their mental health. However, there is little research in the sector to quantify objectively the prevalence of mental health conditions, such as stress, anxiety and depression. The physical wellbeing of commercial pilots is systematically verified by annual medicals – mental health is not so easily established.ICAO’s Manual of Civil Aviation Medicine, published in 2012, suggests that medical reviews should include questions about “psychiatric disorders or inappropriate use of psychoactive substances”. But that same manual asserts that psychological tests of aircrew are “rarely of value” and not “reliable” in predicting mental disorders (IATA 2015). The very nature of flying – fatigue, time zones, extended time away from home, night flights, irregular rostered lifestyle, which puts one out of sync with friends and family – can contribute to poor mental health. Moreover, responsibility and the stress of the job is increased by recent mass redundancy or employment uncertainty in an aviation market crippled by a global pandemic. It is no coincidence that pilots often negotiate for enhanced terms and conditions or security, rather than a pay rise, as they aim to strike a lifestyle balance that is sustainable in the long term. When the market picks up, pilots who will have had the trauma of being made redundant will be coming back into the sector with the additional challenge of upskilling and performing to the level required to fulfil their roles. External factors such as these contribute to the state of our mental health. With COVID-19 and associated anxiety, it will only magnify the problem, and mental health issues in the flying community will surely continue to challenge. Stop and reflect While COVID-19 has been devastating, it has highlighted the importance of proactively recognising our own mental health and wellbeing. As programmes are cut to 30 per cent of 2019 levels, and staff are on stand-down, there is an opportunity to stop, pause and reflect, and to invest in creating resilience and a strong mental health culture in the aviation sector and pilot community. This is the time to improve understanding and create a culture that enables pilots to return to an informed workplace, energised and motivated, not under-confident and anxious. A holistic multilayered approach to managing mental health starts with creating a positive culture in the airline industry, which must be driven and invested in from the top down. Creating a positive mental health culture at company level will take time and commitment. It should promote openness and awareness, supported by management behaviours, and reassure employees that their company cares about their wellbeing. Awareness of mental health can and must be raised by providing information, education, support and training. In 2007, the Air Line Pilots Association conducted studies on pilot personality: The Pilot Personality, Air Line Pilot magazine. It identified 24 personality traits that airline pilots tend to exhibit, including: ● Self-sufficient ● More analytical than emotional ● Bimodal (black/white, on/off, good/bad, safe/unsafe) ● Tend to modify environment instead of their behaviour ● Do not handle failure well ● Low tolerance for personal imperfection ● Long memories of perceived injustices ● Avoid introspection ● Have difficulty revealing, expressing, or even recognising feelings ● When experiencing unwanted feelings, a tendency to mask them with humour or anger This broad overview gives us insight into the personality types recruited into the profession. These traits are indicative of individuals who could find it challenging to be open about their mental health, and underlines the challenges ahead in the airline industry and the importance of proactively managing mental health and resilience. Put any of these traits into an environment where mental health is not talked about for fear of loss of licence, and is it any wonder that pilots have kept the state of their mental health to themselves? A positive company culture may already exist, but it is fundamental that pilots develop their self-awareness and take responsibility for understanding their own mental health. As with any skill, training is key to developing our own self-awareness, resilience and management of mental health, and to watch for warning signs in others. Resilience is so much more than attending a workshop – resilience comes from within us, our self-awareness, mindfulness, self-care, positive relationships and purpose. Claude Thibeault, IATA’s medical adviser, believes that “the approach to reducing mental health risk needs to be multilayered”. Thibeault affirms that “self-reporting or colleague intervention will be paramount to any successful initiative to combat mental health issues, creating a non-punitive environment that encourages self-reporting without unnecessary recrimination”. A moment of introspection When thinking about mental health, the stress bucket is a great analogy for understanding why sometimes we can cope, and other times we cannot. We all have a capacity to deal with stress, and the level of a person’s vulnerability is represented by the size of the stress bucket into which everyday stress flows (see Figure 1). The size of the bucket represents your capacity to deal with stress, and the water level is the amount of stress you are experiencing. Those who are more resilient will tend to have a larger bucket and can cope with additional stress. If you experience high levels of additional stress because of significant changes in your life (rising level), your bucket is prone to overflow. Relationship issues, debt, poor sleep, uncertainty, job insecurity and dealing with change all contribute to stress in our everyday life. Your bucket can be emptied by creating strategies that help you de-stress, such as engaging with things that make you feel connected and happy. When you focus on your problems it creates negative thoughts, which adds to your bucket, making it more likely to overflow. Key to good mental health is engaging with activities that help empty the bucket: the level is lowered by using strategies to reduce your stress. Whatever it takes to change your focus, calm your physiology, manage that inner negative chatter in your head and to give your mind a break. A great de- stressor is to put yourself in ‘flow time’ every day, when you do something that takes your mind off the here and now, and in which you are so absorbed you do not notice time passing. This could be exercise, mindfulness, talking to inspirational friends, playing sport – whatever puts you in the flow. Problems occur when you stop using your coping strategies to reduce stress. Levels rise in the bucket and you are more likely to feel overwhelmed and out of control. Then, emotional snapping may occur and can be triggered by the smallest of things; perhaps an ill-placed comment in a supermarket queue or being burned up at the traffic lights. This is when you notice your stress signatures, as the stress impacts on your physiology. Feeling overwhelmed We are all unique in the way stress creates our stress signatures and the strategies we need to manage our mental health. Psychological signatures can be irritability, lack of confidence, low self-esteem, emotional fragility, aggression, indecision, and poor concentration or memory. Physical signatures include fatigue, frequent minor illnesses, difficulty sleeping, weight loss or gain, gastrointestinal disturbances, and skin irritation, such as eczema. Some people may display behavioural signatures – for example, erratic, unacceptable behaviour; being louder than normal; talking quickly; increased errors; overworking, and not getting things done. These are signs that you are feeling overwhelmed and all is not well. If you ignore these signs and do not invest time in self compassion, and use strategies to reduce your stress, you become at risk of developing mental illness, such as anxiety and depression. When you have an understanding of how you are feeling – noticing when your stress levels are rising and having strategies to manage – you will feel more in control and will no longer feel overwhelmed. Talking to friends and family, sharing your feelings, is a great way of gaining clarity. With the aviation sector being turned on its head, pay and terms and conditions being downgraded, mass redundancy and zero recruitment, it is important to take time to reflect and develop an understanding of mental health in aviation – and the potential consequences if left unchecked. A top-down culture promoting a supportive environment must be instigated, and mental health policies that detail how the culture will be embedded in company practices should be clear and unambiguous. While the rosters are quiet, it is time to work with those pilots in employment to develop their resilience to sustain them through this uncertain period. Pilots exiting the business through redundancy should be supported to develop their resilience and enable them to return to the profession energised and motivated, rather than anxious and fearing failure. Remember, these are the pilots of the future. If you do not invest time in self compassion, and use strategies to reduce your stress, you become at risk of developing mental illness. Louise Pode SRP BSc (Hons), MSc, resilience and stress management consultant, ProAbility: www.ProAbility.co.uk; louise.pode@ProAbility.co.uk