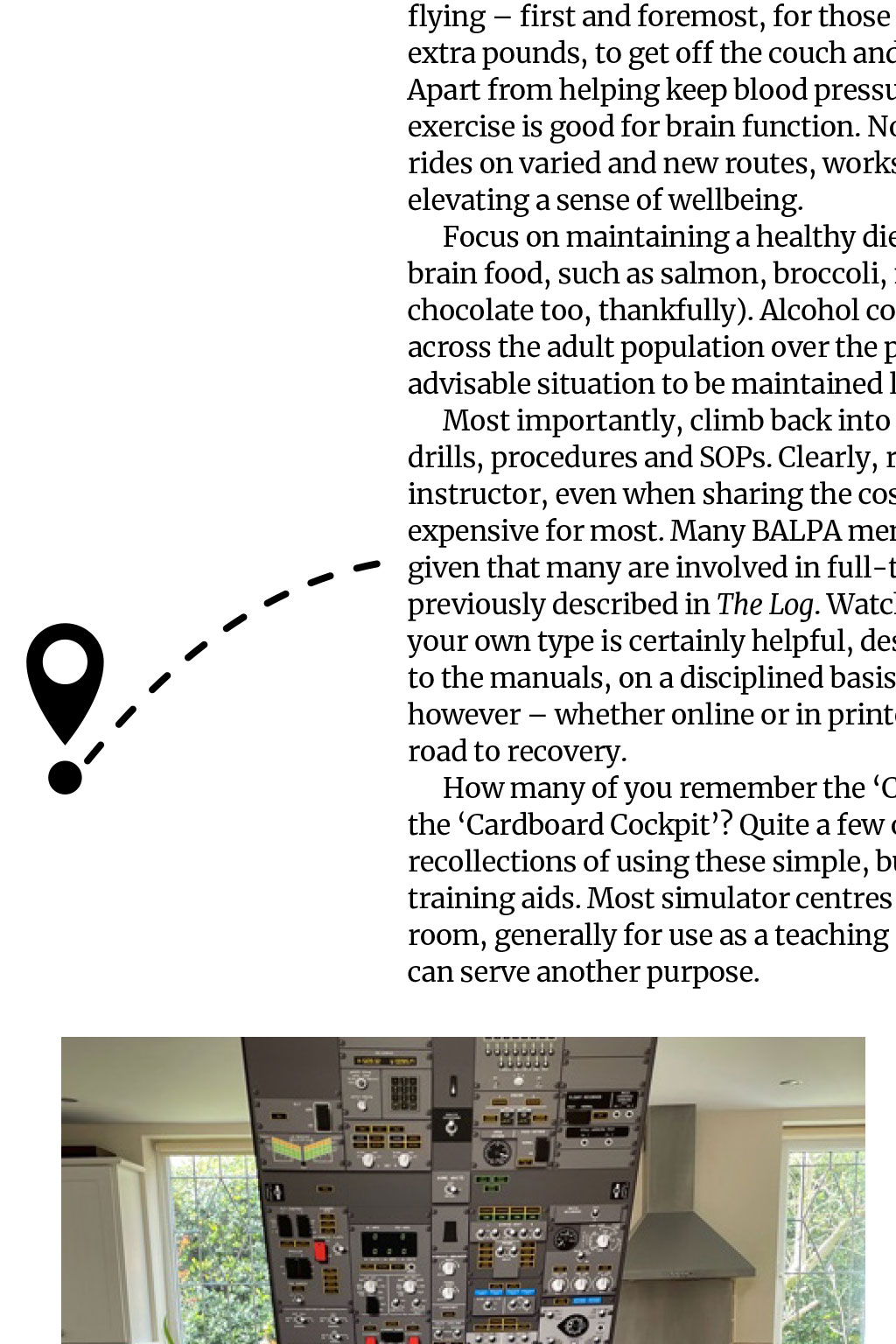

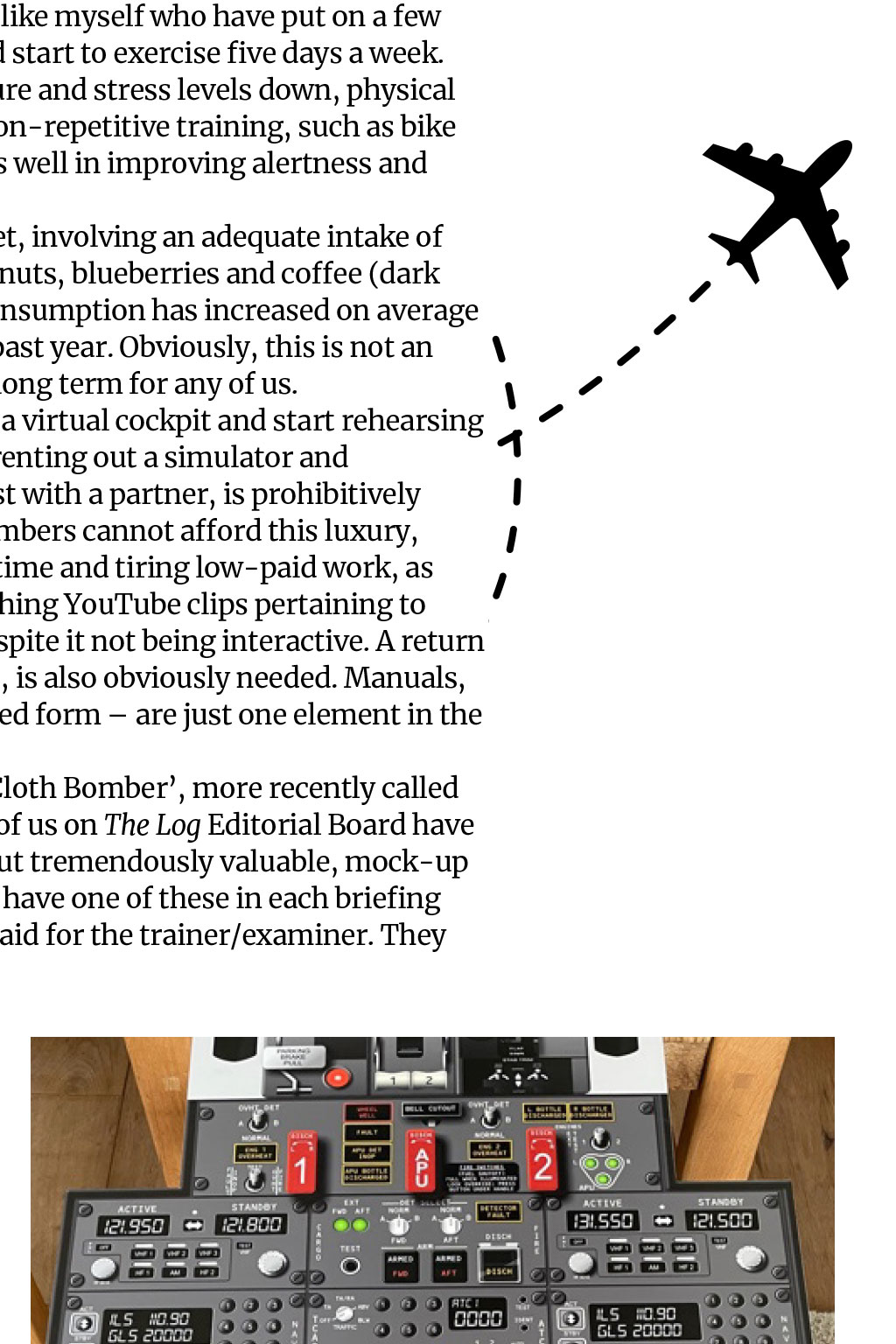

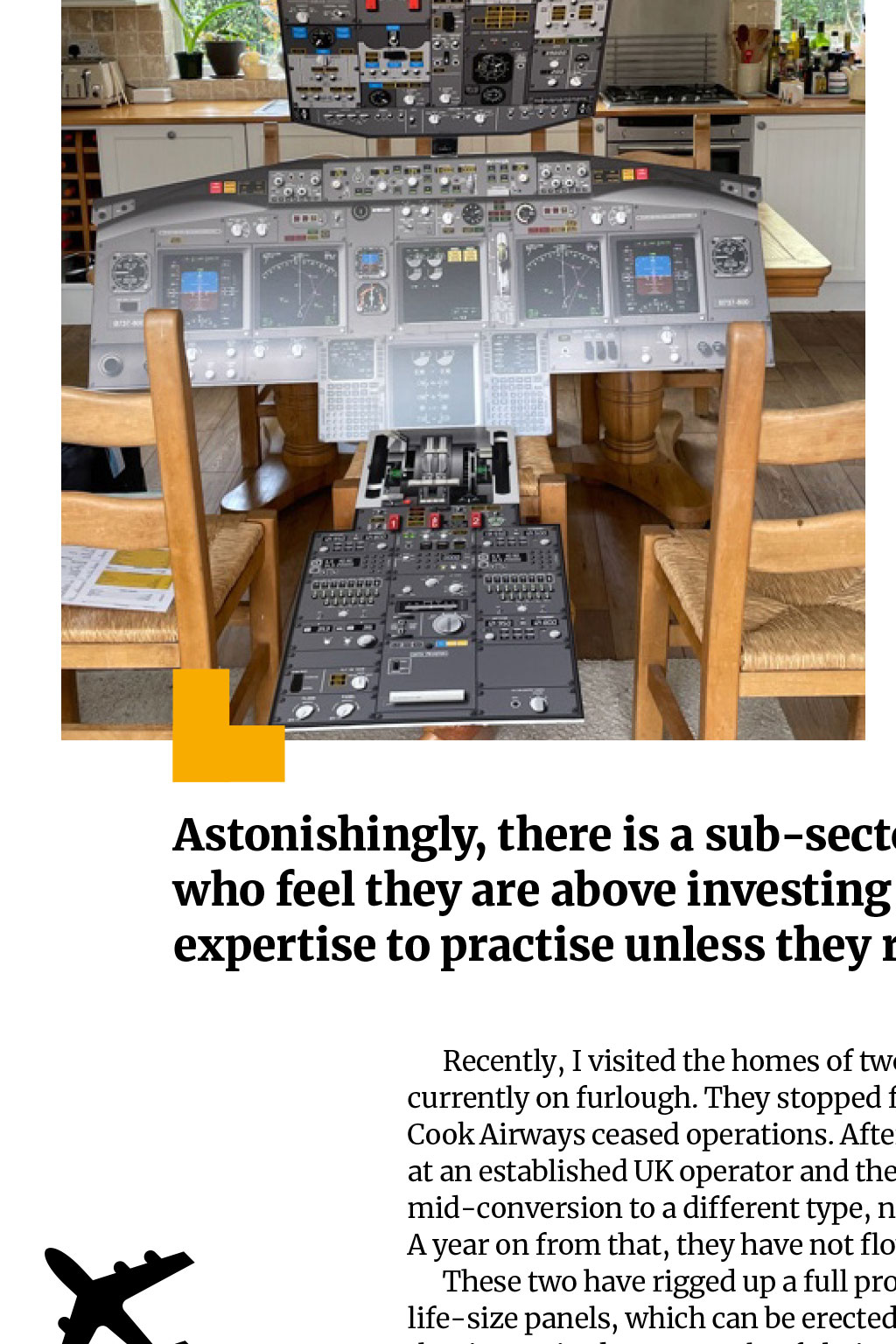

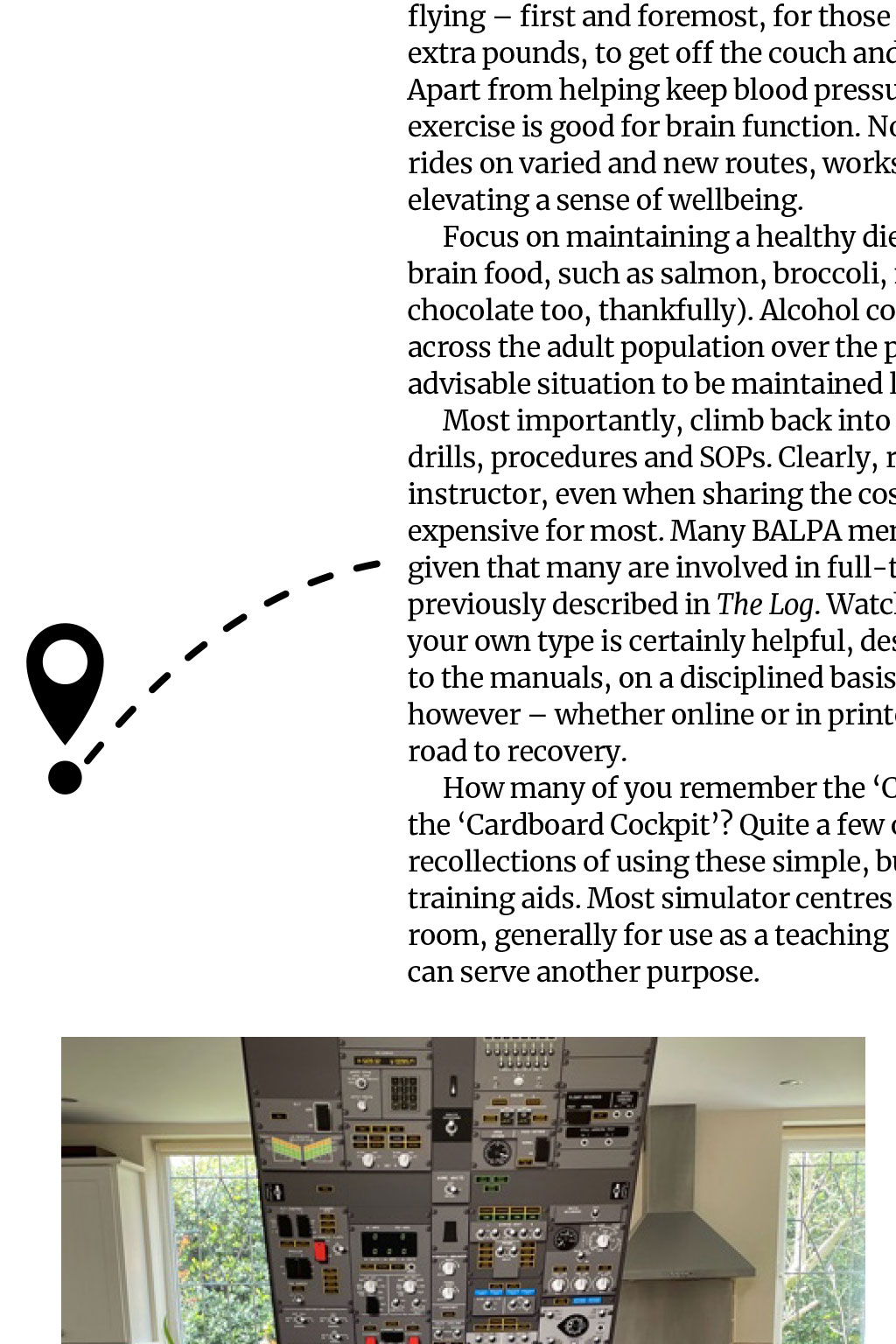

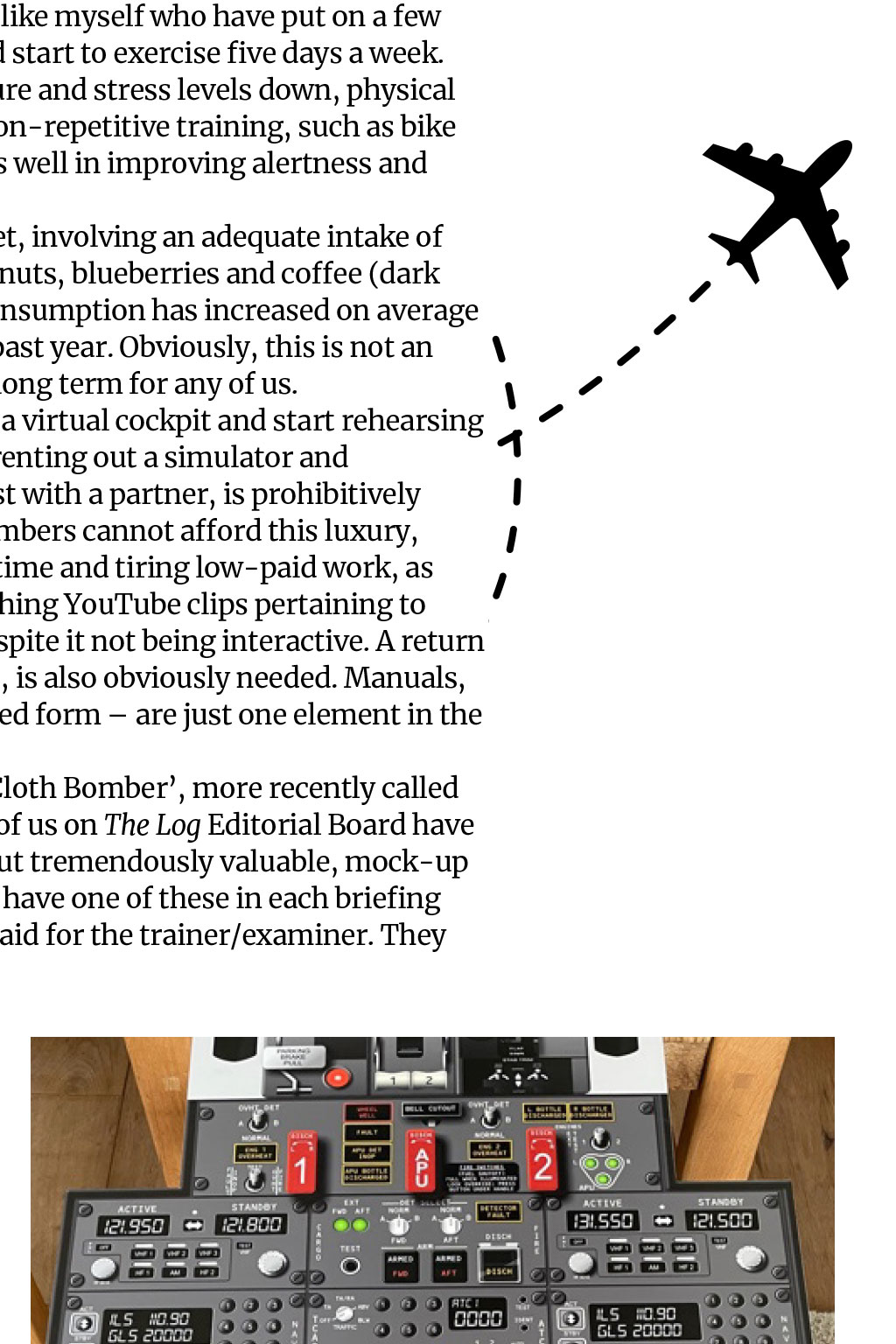

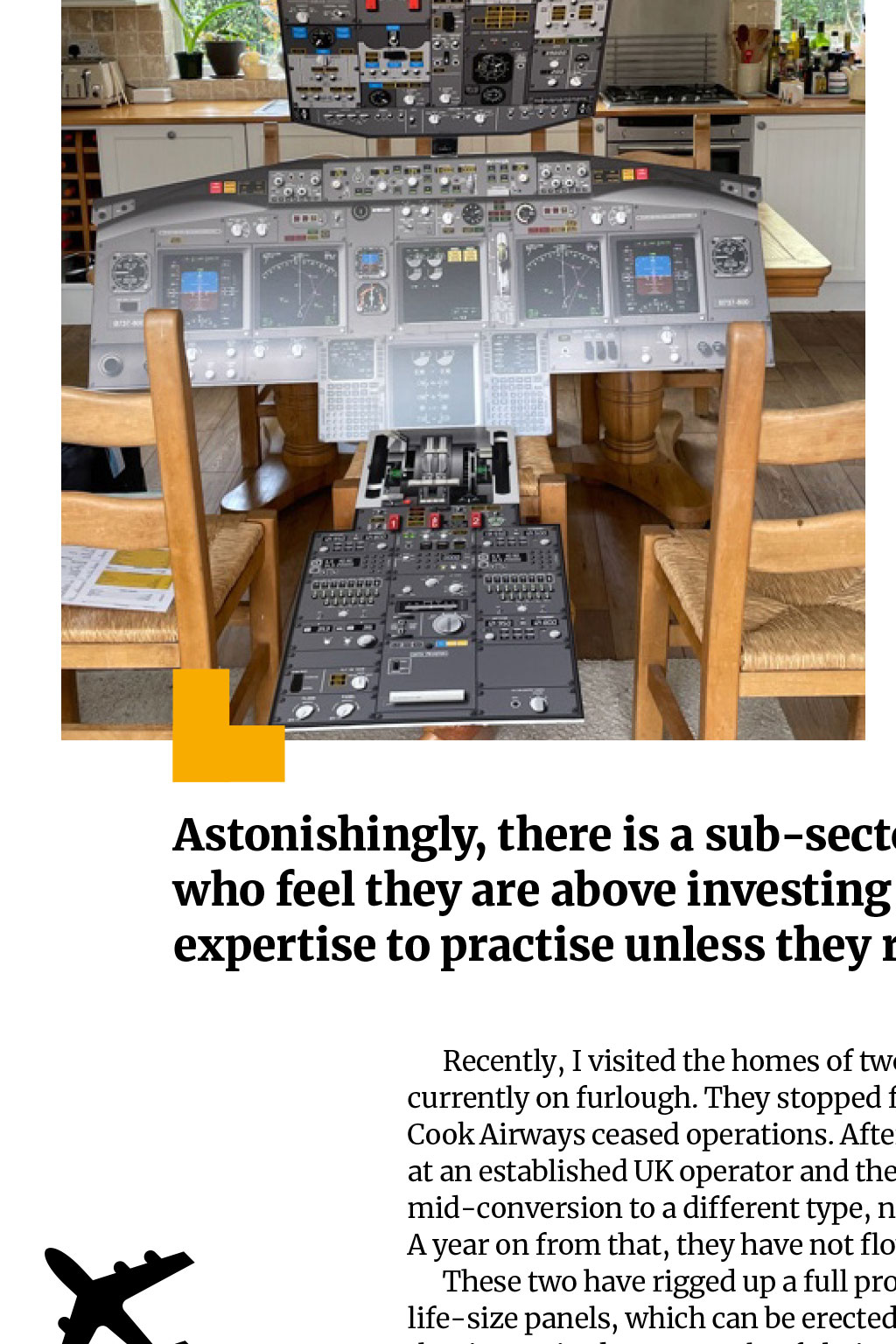

FIT FOR FLYING WORK Bringing pilots out of mothballs is no easy task HOME K R O W By David Keen, Log Board member HOME t is clear that bringing thousands of airliners out of storage will involve considerable time, energy and cost. This process is relatively easy to calculate and schedule, although a temporary shortage of licensed and current engineers may occur. This would clearly lengthen the release time for those many jets sitting in deserts and on remote airfields. However, the problem facing airlines when it comes to bringing their pilots back on line is one of greater magnitude and complexity. First, just consider the number of operating air crew required per aircraft. Even on limited schedules, the numbers can range between 10 and 16 in-check pilots for each twin-jet aircraft, more for the long-haul B787 and A350s now in vogue. The simulator and line-training time needed adding ground school, final checks and, perhaps, re-tests will dramatically outweigh the available capacity of trainers and simulators. The process of restoration of flight operations is, therefore, sure to be slow, costly and labour-intensive. Perhaps this will fit in anyway with the slow uptick of domestic and international air travel. Passengers will be wary, governments will be cautious, and the public acceptance of a reasonable level of COVID risk may take a few years to evolve. Nevertheless, the time is now ripe for aviators brains to fire up, and for working memories to be restored and updated. Apart from those few fortunate folk who have been flying the line, there is a huge pool of qualified pilots who have not been called on to work for more than 12 months. When I recall the sense of rustiness that I felt after returning to work after two or three weeks of leave, I cannot imagine how much more corroded my skill set would be after such a long lay-off. In aviation history, there has never been such a lengthy stand down for almost the entire pilot population. Many thousands worldwide have lost their jobs. Further thousands have been furloughed. In alleviation, a significant number have chosen to take early retirement or pursue alternative careers. Taking steps Let us look at the best steps forward that can be taken to aid return to flying first and foremost, for those like myself who have put on a few extra pounds, to get off the couch and start to exercise five days a week. Apart from helping keep blood pressure and stress levels down, physical exercise is good for brain function. Non-repetitive training, such as bike rides on varied and new routes, works well in improving alertness and elevating a sense of wellbeing. Focus on maintaining a healthy diet, involving an adequate intake of brain food, such as salmon, broccoli, nuts, blueberries and coffee (dark chocolate too, thankfully). Alcohol consumption has increased on average across the adult population over the past year. Obviously, this is not an advisable situation to be maintained long term for any of us. Most importantly, climb back into a virtual cockpit and start rehearsing drills, procedures and SOPs. Clearly, renting out a simulator and instructor, even when sharing the cost with a partner, is prohibitively expensive for most. Many BALPA members cannot afford this luxury, given that many are involved in full-time and tiring low-paid work, as previously described in The Log. Watching YouTube clips pertaining to your own type is certainly helpful, despite it not being interactive. A return to the manuals, on a disciplined basis, is also obviously needed. Manuals, however whether online or in printed form are just one element in the road to recovery. How many of you remember the Cloth Bomber, more recently called the Cardboard Cockpit? Quite a few of us on The Log Editorial Board have recollections of using these simple, but tremendously valuable, mock-up training aids. Most simulator centres have one of these in each briefing room, generally for use as a teaching aid for the trainer/examiner. They can serve another purpose. A homemade flight deck in the kitchen of a furloughed pilot, used to practise drills Astonishingly, there is a sub-sector of entitled pilots who feel they are above investing their time and expertise to practise unless they receive payment Recently, I visited the homes of two former colleagues who are currently on furlough. They stopped flying Airbus aircraft when Thomas Cook Airways ceased operations. After a long pause, they gained positions at an established UK operator and then abruptly stopped flying again on mid-conversion to a different type, namely the much-evolved Boeing 737. A year on from that, they have not flown. These two have rigged up a full procedures trainer in the form of life-size panels, which can be erected to look like a 737 flight deck. All that is required are a couple of chairs, a table and a hanger to use from the ceiling and a willingness to put in the hours. Although there are no moving parts, touch drills provide the essence for developing and instilling familiarity of the layouts from both seats perspectives. Drills can be practised using a generic quick reference handbook, which was devised and prepared in-house. By working methodically for up to four hours at a time, at least twice a week, these motivated individuals have built up a readiness to perform well in the simulator and the aircraft at relatively short notice. As we all know, this is vital for confidence, that asset so essential for our profession. This would seem an obvious and cost-effective step to take in these challenging times, but not everybody has gone up this road. Astonishingly, there is a sub-sector of somewhat entitled pilots who feel they are above investing their time and expertise to practise unless they receive payment. Even when being paid, some furloughed folk have done little or nothing to stay current. Relying solely on past experience is a trap for the unwary. Erosion of skills happens quickly, as referred to below. To be fair, some people are still in a state of shock, unable to come to terms with the sudden cessation of their careers in early 2020. These individuals will also find it extremely challenging to return to full-time flying successfully. Skills degradation Conventional wisdom within the aviation community is that pilots who have not demonstrated proficiency in instrument flight procedures for more than six months are unsafe in instrument flight operations. Furthermore, research into skills degradation suggests that, without regular performance of complex tasks, procedural and motor skills degrade over a fairly short timeframe. Procedural knowledge decays more quickly than motor skills. In essence, stick and rudder abilities remain with us longer than those associated with more complex tasks, such as abnormal procedures and emergency procedures although, often, the two are combined. Age-related memory loss is well-documented, suggesting that older pilots may experience greater difficulty in picking up the reins after this lengthy time period. For low-time pilots, the learning curve to reacquire recently learned and now degraded skills may be exceptionally steep. In conclusion, as aviation slowly climbs back towards its previous peak, it is strongly recommended that an investment of time, rather than money, will help pilots prepare for their return to this most rewarding and satisfying of careers. A number of organisations exist that provide materials and programmes to support your efforts to get back in the saddle. Start with the Redundancy Advisory Group on the BALPA website. An online search of cockpit posters will also unveil companies that provide low-cost training materials, cockpit posters and the like, to help kick-start your return to flying. Fluency in the flight deck will be looked for in all pilots getting back to work, so anticipation and preparation are vital.