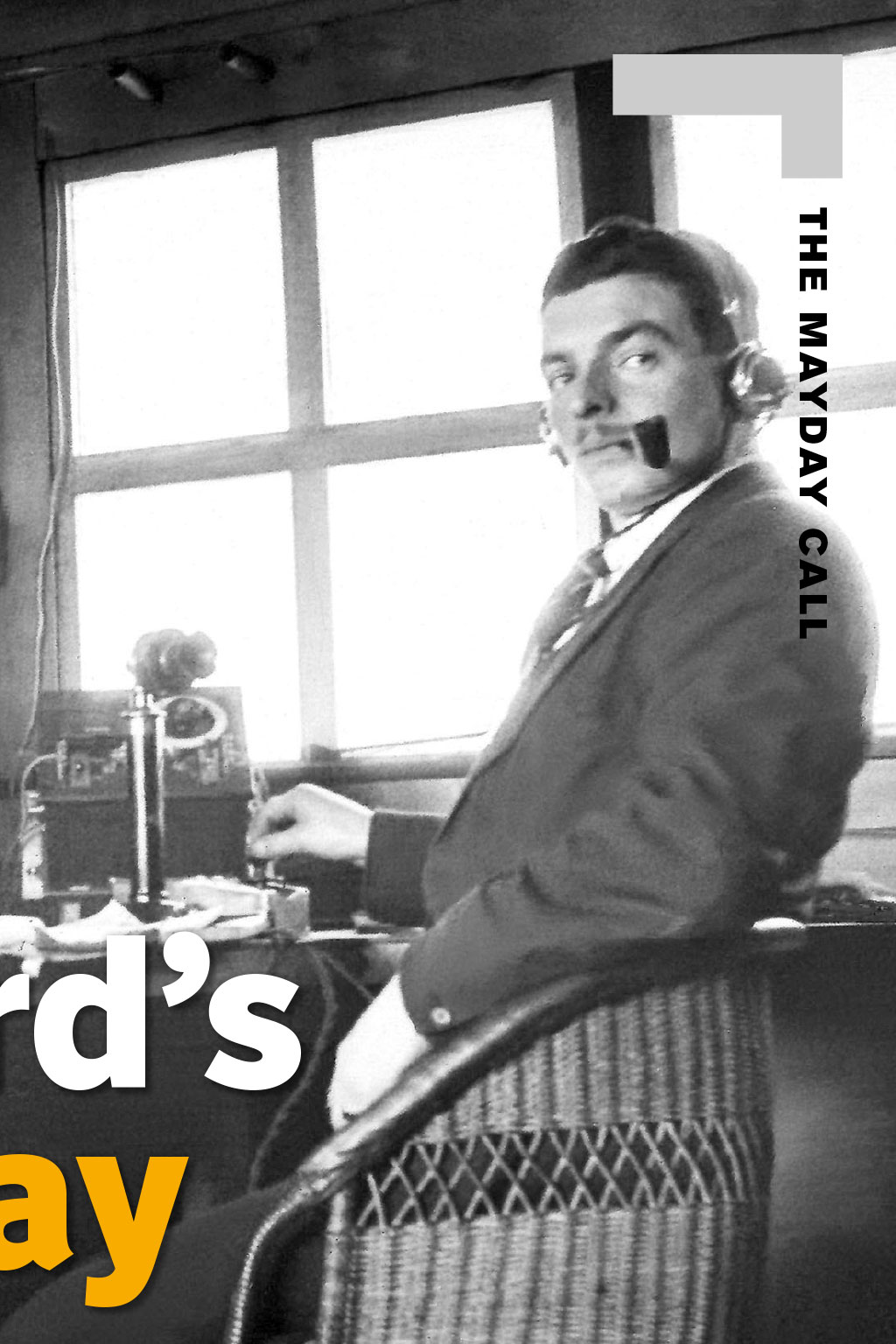

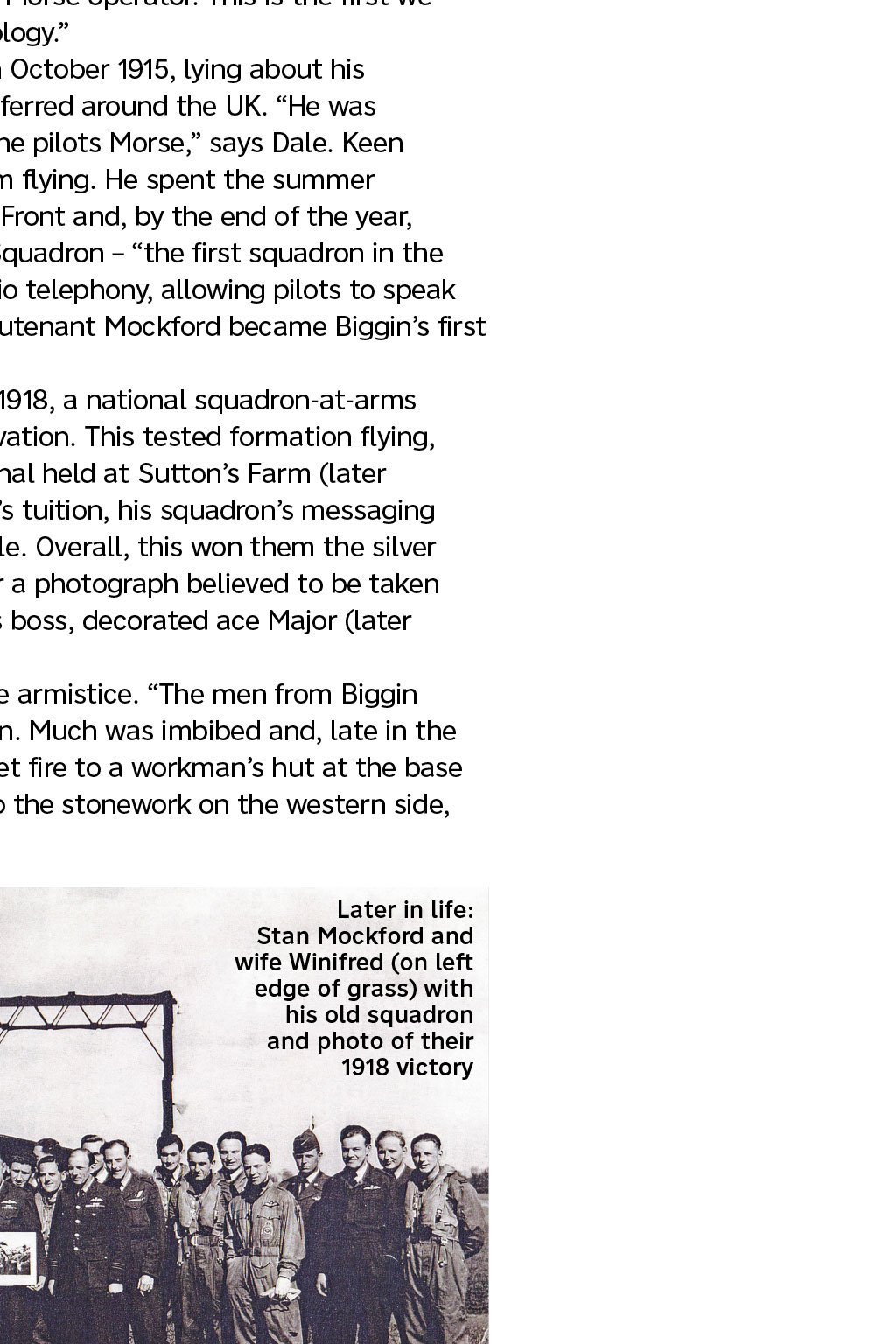

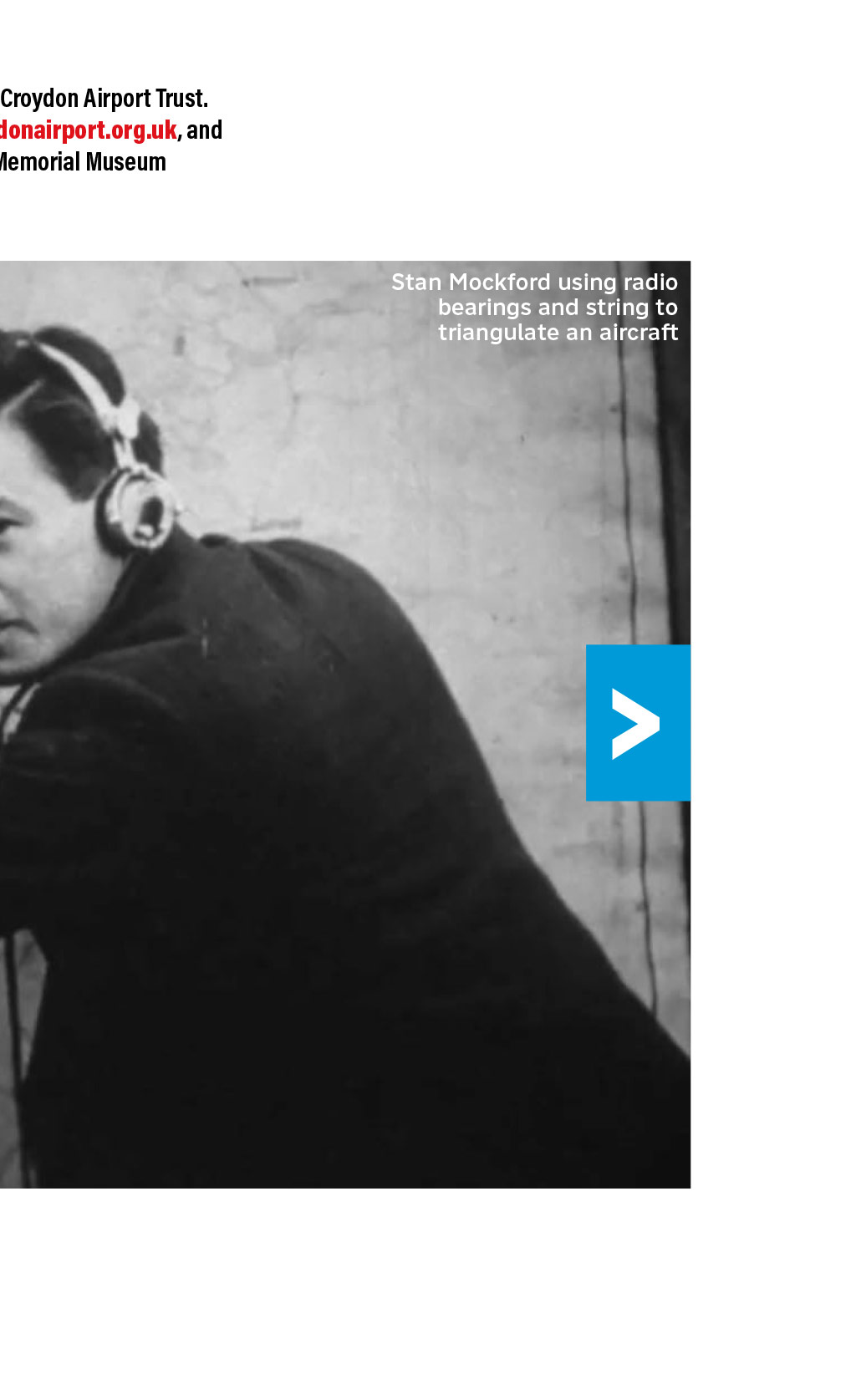

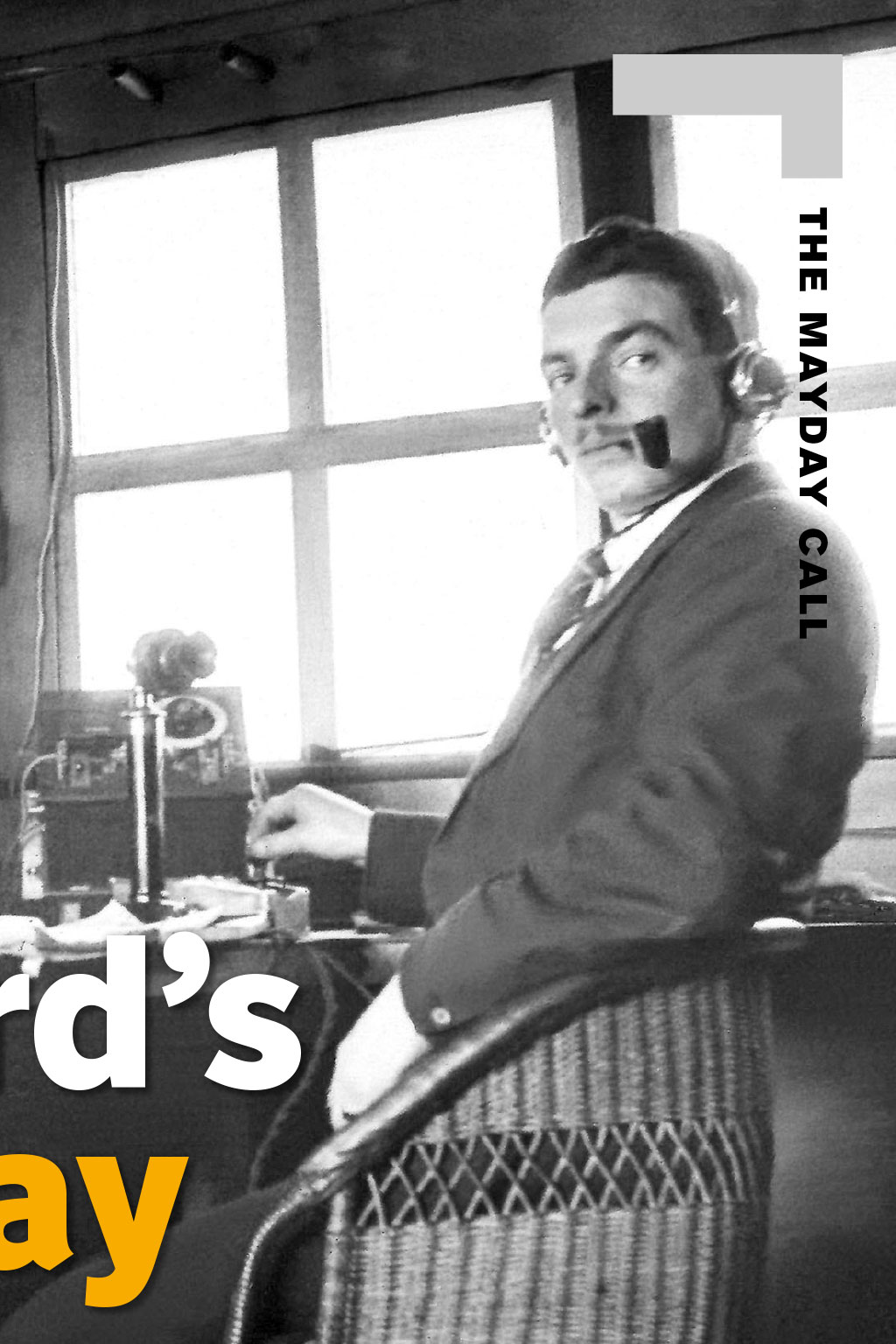

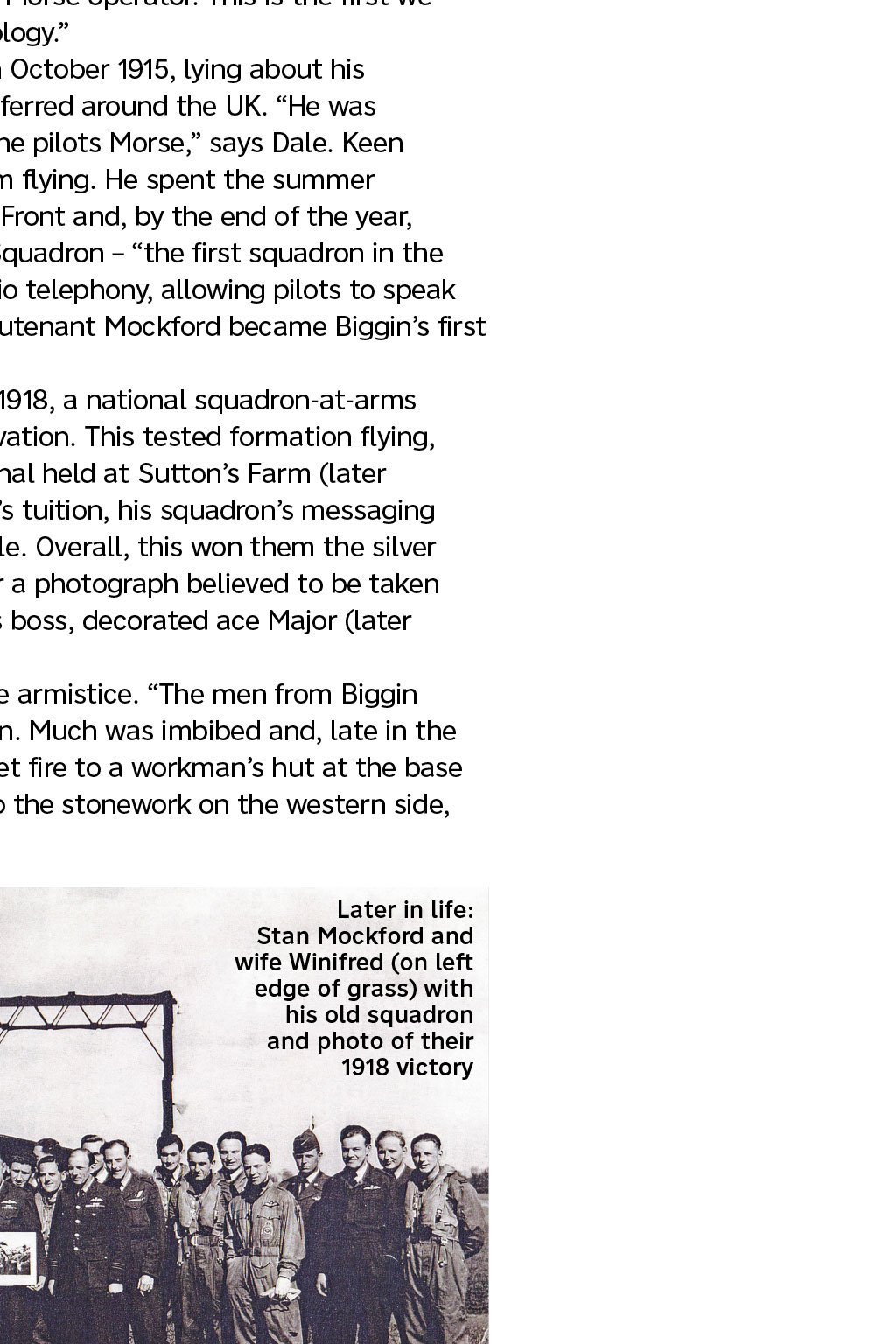

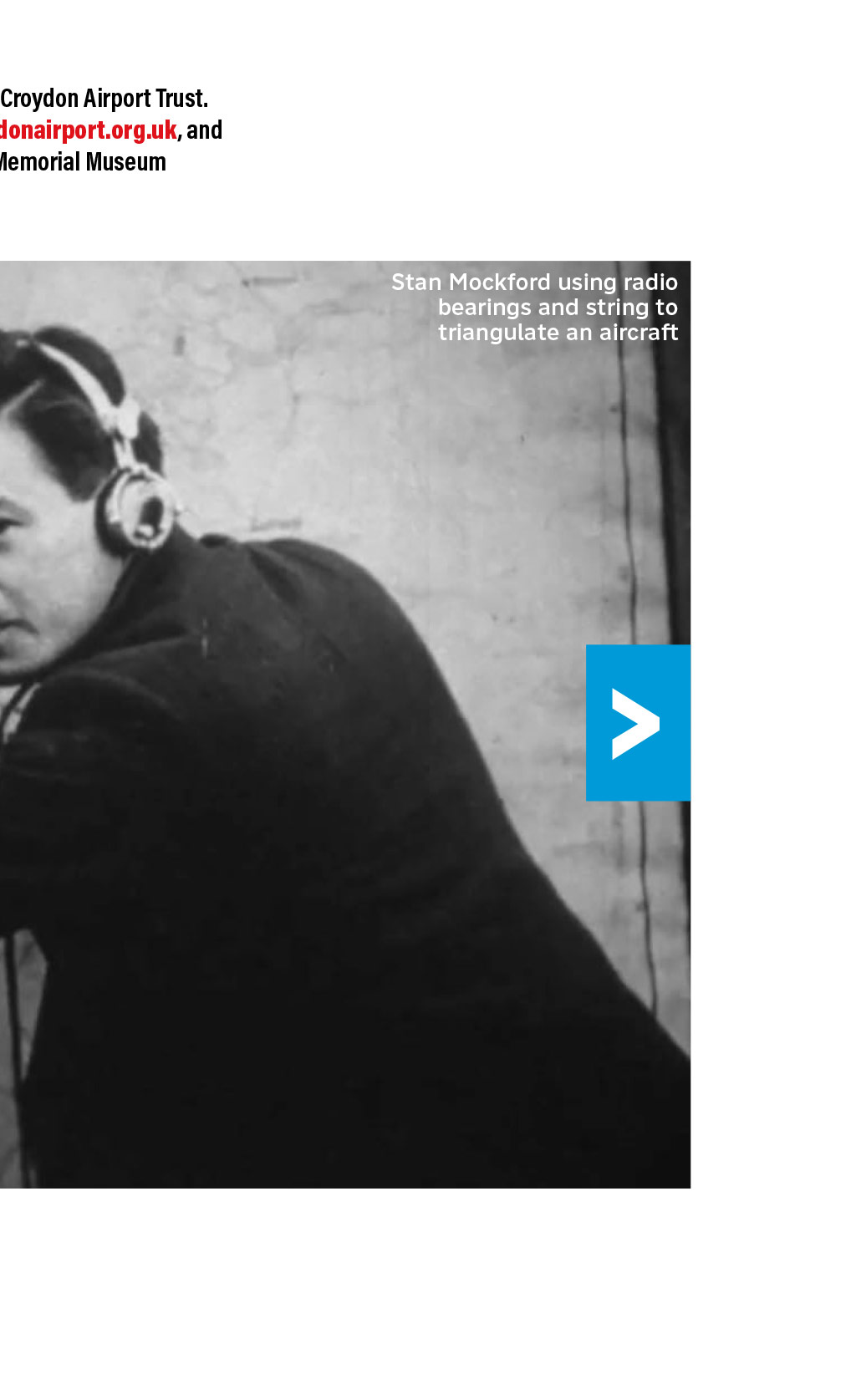

THE MAYDAY CALL Mockfords Mayday Stan Mockford in the Croydon Radio Office c.1922 The history of the distress call owes much to a wizard of wireless By Captain Robin Evans, Senior Log Contributor canning headlines of the past year, there has been a distinct uptake in the usage of Mayday outside the profession. Its origins are intrinsically linked to the wider centenary of air traffic control, currently ongoing, but where did it start and why? At the end of the 19th century, the development of wireless accelerated, rendering visual signalling, such as semaphore, obsolete. Early land telegraphs adopted the letters CQ, from the initial sounds of the French scurit alert all stations, known as seek you. There was no emergency signal, but the letter D (distress) was used separately to indicate urgency. In 1904, dominant radio pioneers the Marconi Company recommended combining the two codes as their company standard: CQD. This was the earliest understood form of broadcasting all stations: distress, remembered as come quickly, disaster. It was not endorsed internationally, as it could still be mistaken for CQ in a weak transmission; a specific distress call did not yet exist. Meanwhile, German naval stations were using three standardised signals: ruhezeichen (stop), suchzeichen (query) and notzeichen (emergency). The latter combined the elements --- in one transmission, as opposed to the equivalent, spaced, S O S. The nine-character signature was unique. Marconi and its nearest rival, Telefunken, formally agreed to adopt SOS in 1906. Only later was it adopted as a reversible, visual signal, or a meaning applied to the acronym. Water Both CQD and SOS were in use in April 1912 as the Titanic set sail, the first use of SOS having occurred several years before. Marconi wireless operators Jack Phillips and Harold Bride were preoccupied dispatching the commercial messages of affluent passengers throughout the fateful evening. Their powerful radio was considered more a luxury than a means of operational necessity. An earlier technical issue had caused a backlog of messages, resulting in a delay in relaying the first reports of icebergs, received without the urgency prefix and, so, unprioritised. Phillips initiated the distress call at 00.15 local: CQD SOS Titanic position 41.44 N 50.24 W. Require immediate assistance. Struck an iceberg. Sinking. His final transmission came at 02.17, leaving his station as the radio room filled with water, long after being ordered to abandon. Only Bride survived, later confirming he reminded Phillips: Send SOS. Its the new call and it may be your last chance. More than 700 survivors owed their lives to Marconis invention and a standardised way of using it, but the subsequent investigation revealed multiple shortcomings. Though advanced for the time, spark-gap radios produced noisy transmissions that bled across a large bandwidth. There was no controlling authority and no procedures of silence during an emergency, exacerbated by multiple vessels in the vicinity. Questions of the priority of non-operational messages over operational ones were also raised. Finally, transmissions were still only useful for Morse telegraphy; voice telephony would not appear until the end of the decade. Ultimately, the initial iceberg warning made by the nearby SS Californian was lost in the backlog of commercial messages. The same vessel then misunderstood distress flares and, without listening-watch, steamed on. Guglielmo Marconi himself proposed a permanent listening-watch or an automated alarm triggered by the distress prefix. These early lessons were fundamental to shaping maritime communications. The Titanic is a fair parallel for our own 1977 Tenerife disaster: a notorious event forcing an evolution in communications. Air Aviation began asserting itself on the airwaves during World War I, championed particularly by one man: Frederick Stanley Mockford Stan to his friends. Born on 8 December 1897, in Seaford, East Sussex, his legacy is explained by his grandson Dale Mockford. Stan joined London, Brighton and South Coast Railways, and trained as a Morse operator. This is the first we know of his interest in emerging technology. Stan joined the Royal Flying Corps in October 1915, lying about his age. Throughout 1916 and 1917 he transferred around the UK. He was moving between squadrons, teaching the pilots Morse, says Dale. Keen to reciprocate, they sometimes took him flying. He spent the summer of 1917 laying landlines on the Western Front and, by the end of the year, had transferred to Biggin Hill with 141 Squadron the first squadron in the world to be equipped with two-way radio telephony, allowing pilots to speak to each other, explains Dale. Flight Lieutenant Mockford became Biggins first wireless operator. With conflict abating by September 1918, a national squadron-at-arms competition was held to maintain motivation. This tested formation flying, aerobatics, gunnery and wireless, the final held at Suttons Farm (later RAF Hornchurch) in Essex. Under Stans tuition, his squadrons messaging was the only perfect result, reports Dale. Overall, this won them the silver cup and the title of Cock Squadron for a photograph believed to be taken by Stan: a live cockerel held aloft by his boss, decorated ace Major (later Air Marshal) Brian Baker. There was more celebration upon the armistice. The men from Biggin decided to celebrate by going to London. Much was imbibed and, late in the evening, they gathered materials and set fire to a workmans hut at the base of Nelsons Column, causing damage to the stonework on the western side, still visible today. Later in life: Stan Mockford and wife Winifred (on left edge of grass) with his old squadron and photo of their 1918 victory Sat with a professional forebear of a century ago, the only overlap between respective standards would be Charlie, X-ray and Vic(tor) Genesis Stans skills were in demand, first on the Irish broadcasting network, then after demobilisation for Britains fledgling civil aviation industry: Hounslow Heath (1919) and Croydon (1920). Croydon was the UKs first international airport, synonymous with the first developments in Air Traffic Control. An Air Ministry memo of February 1920 reveals a specification for the very first, purposebuilt Aerodrome Control Tower. An 8ft sq hut, 15ft above ground level, with windows in all four walls, it had a railed external gallery and a wind vane on the roof geared to an internal indicator. By 1921, Stan and his colleagues were able to offer direction finding to aircraft from their transmissions. Later that year, triangulation by crosscut from an equivalent station at Pulham, Norfolk, was achieved. A further station, Lympne in Kent also Croydons nominated diversion followed later. A Civil Aviation Traffic Officer (CATO) would manage the traffic flow using pins on a map, passing instructions to a radio officer qualified to speak to aircraft. For their era, the large, valve-driven Marconi radios were cutting-edge. As transmissions were received, the radio officer used a goniometer (an electric directional indicator) to corroborate bearings. Advancing technology after World War II became the catalyst for the integration of both roles. Stan approached the Institution of Electrical Engineers regarding exam papers for wireless. No such papers existed, says Dale, so he took it upon himself to devise a suitable exam in Aircraft Wireless Operation. The first to pass Stans assessment was Jimmy Jeffs, awarded the first Air Traffic Controller licence in 1922. The same year, the Air Ministry approved radio position fixing, with Stan involved in the first poor-visibility talk down. Lingua Franca Dale relates how, in 1923, the Air Ministry asked for a word that pilots could use in distress. Stan settled on Mayday, a corruption of the French maidez. Owing to the majority of international air movements being between Croydon and Le Bourget, plus Brussels, Stan felt this to be an unmistakable cry in emergencies. By 1924, Stan was now Croydons senior radio officer. With the job came a residence on the airfield; Croydon Airport was the recorded birthplace of his third child, Laurence Dales father. The army and navy used their own phonetic alphabets (Ack, Beer and Pip) in World War I. The civil world adopted these, adding a few of its own. There were many versions in many countries, but we think Stans was the first to be used by commercial air traffic in Europe, explains Dale. In 1921, the Air Ministry moved to standardise the unofficial signalese and published a standardised, full-phonetic alphabet, says Ian Walker, of the Historic Croydon Airport Trust. Promulgated for use in radio-telephonic communication in civil aviation, it was also in use by all three military services. Notice to Airmen No.107 of 1921 was the first published phonetic alphabet. Sat with a professional forebear of a century ago, the only overlap between respective standards would be Charlie, X-ray and Vic(tor). A bespoke aviation version of the 1930s employed cities Gallipoli, Amsterdam, Casablanca, Jerusalem. This marked the first appearance of Qubec, the only city to survive. Two syllables, and an unusual sound, probably sealed its longevity. Names were popular with the earliest telephone networks: Mary, Henry and Alice falling by the wayside. A military version was harmonised between Allied forces in World War II, with other agencies retaining their own; Christian names were popular. As these were gradually integrated, we lost earlier iterations, such as Monkey, Uncle and Zebra. Extensive testing and academic research through the 1950s led to our current standard: officially, Juliett emphasises a final, hard t over a soft one for French speakers, and Alfa is considered more universal than the English ph. Legacy With operations booming, Croydon was extended to cater for the increasing volume and size of aircraft, its bespoke terminal opened in 1928 still viewable today. This was the first international terminal in the world to have every function contained within its walls, says Dale. Stans contribution was the design of the iconic wireless tower, but when he provided the details to the Marconi Company, he was told it wouldnt work. He insisted that it be made to his requirements, and it did work until the airport closure in 1959. In 1930, Stan joined the Marconi Company, where he remained for three decades. He travelled the world, setting up radio and TV in many countries, says Dale. He made a big impression in Iceland, where he was awarded a knighthood for his services. In Ghana, he handed over the national TV station to President Nkrumah, who rewarded him with three African Grey parrots. Dales family adopted one Sally. Friends and relatives over the years found Sally to be very entertaining, as she frequently found ways of imitating people. She also had a destructive streak that once included my homework. When I explained to the teacher, he didnt believe me and caned me for making it up. Still working in 1961, Stan became increasingly ill with cancer and died the following year. It was because of his lifetime love of tobacco, says Dale. He had previously been a robust, 14-stone gentleman of 58, and was now a shell of a man. As a 10-year-old, it is an image that has stayed with me all these years. Buried in Selmeston, East Sussex, Stans gravestone records his achievements: Air radio pioneer and originator of the distress call Mayday. The BBC concurred, appropriately broadcasting a radio feature. Relevant Stan was ambitious, recalls Dale. He didnt want to follow in the family farming tradition and showed an early interest in the latest technology of the time. His recorded voice was quite clipped and somewhat BBC, but recordings show he liked a joke, reverting to his native Sussex burr to deliver them. He was very gregarious and affable. He liked a party and socialising with every level, from presidents to juniors at Marconi. He has always been regarded highly within the family. We grew up knowing of his achievements, and I particularly remember being full of admiration for him. You may never have to use them, but now you might remember how one man and two syllables opened the door to a world of help. Mockfords Mayday will be a century old in two years but, in the current climate, more relevant than ever. Thanks to Dale Mockford and Ian Walker, Historic Croydon Airport Trust. Croydon is open to visitors at www.historiccroydonairport.org.uk, and exhibits to Stan Mockford exist at the Biggin Hill Memorial Museum First air traffic controller James Jimmy Jeffs, Croydon c. 1928 Stan Mockford using radio bearings and string to triangulate an aircraft The original specification control tower of 1920 at Croydon Croydon controllers: radio officers communicating with their CATO via a hatch c.1928