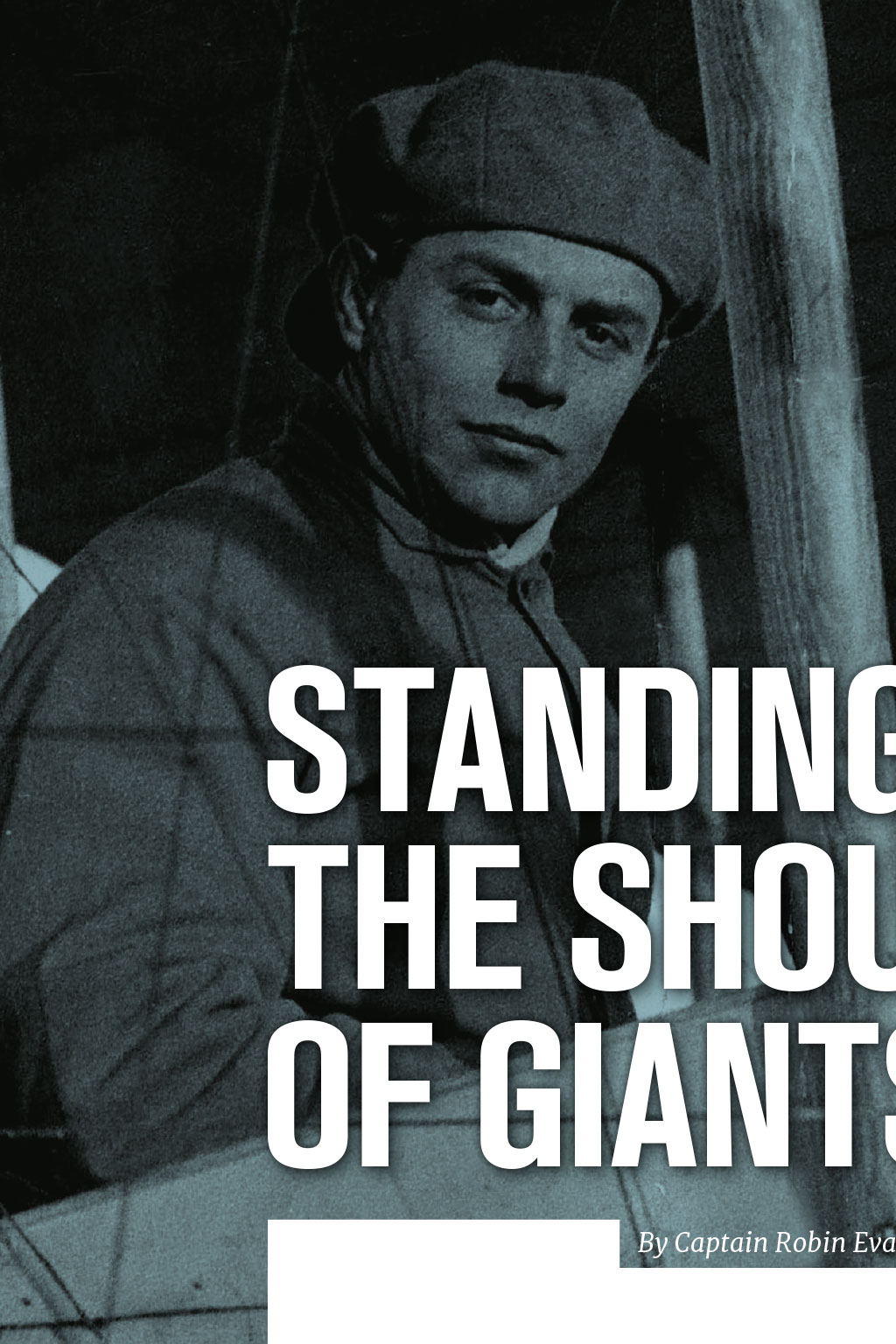

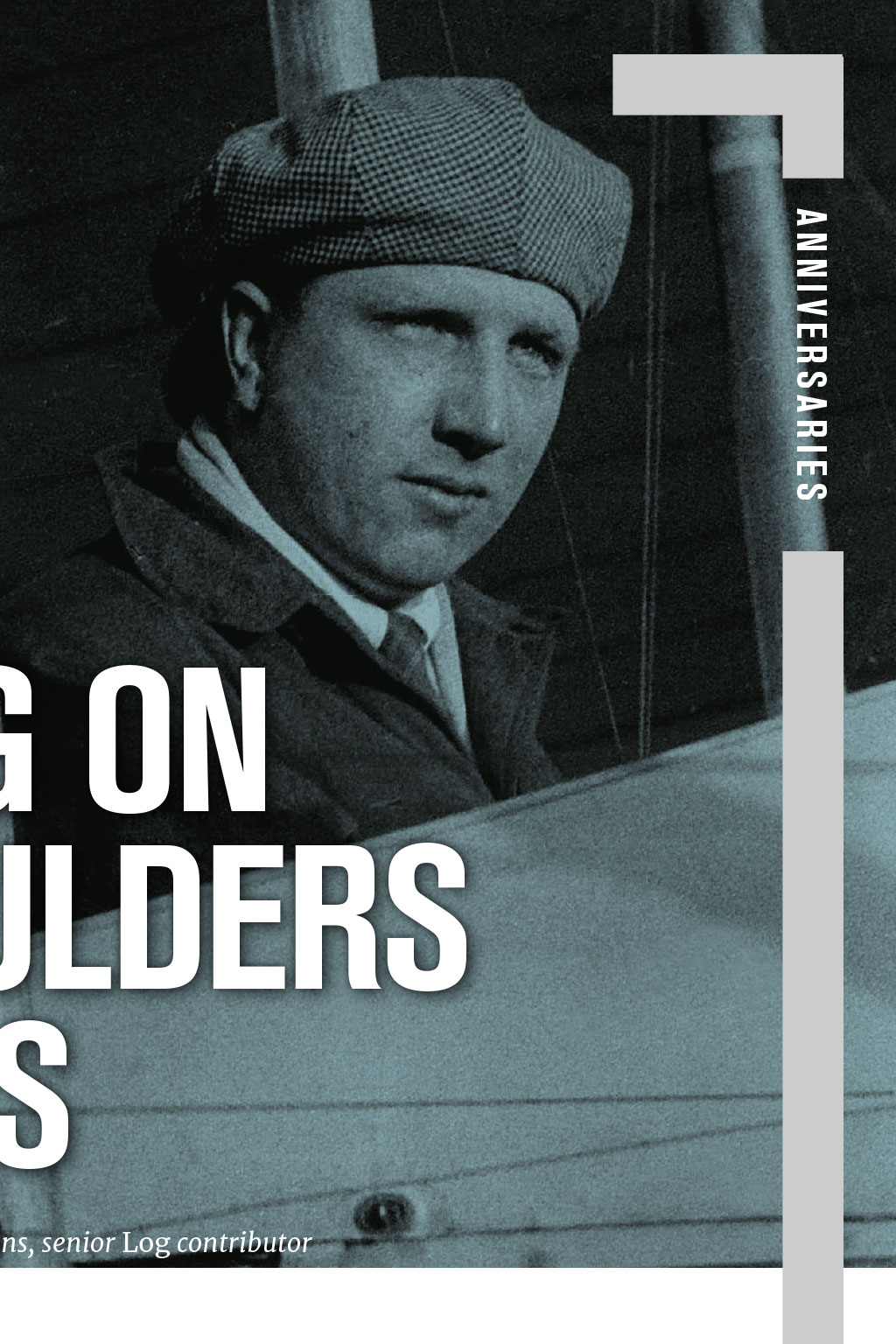

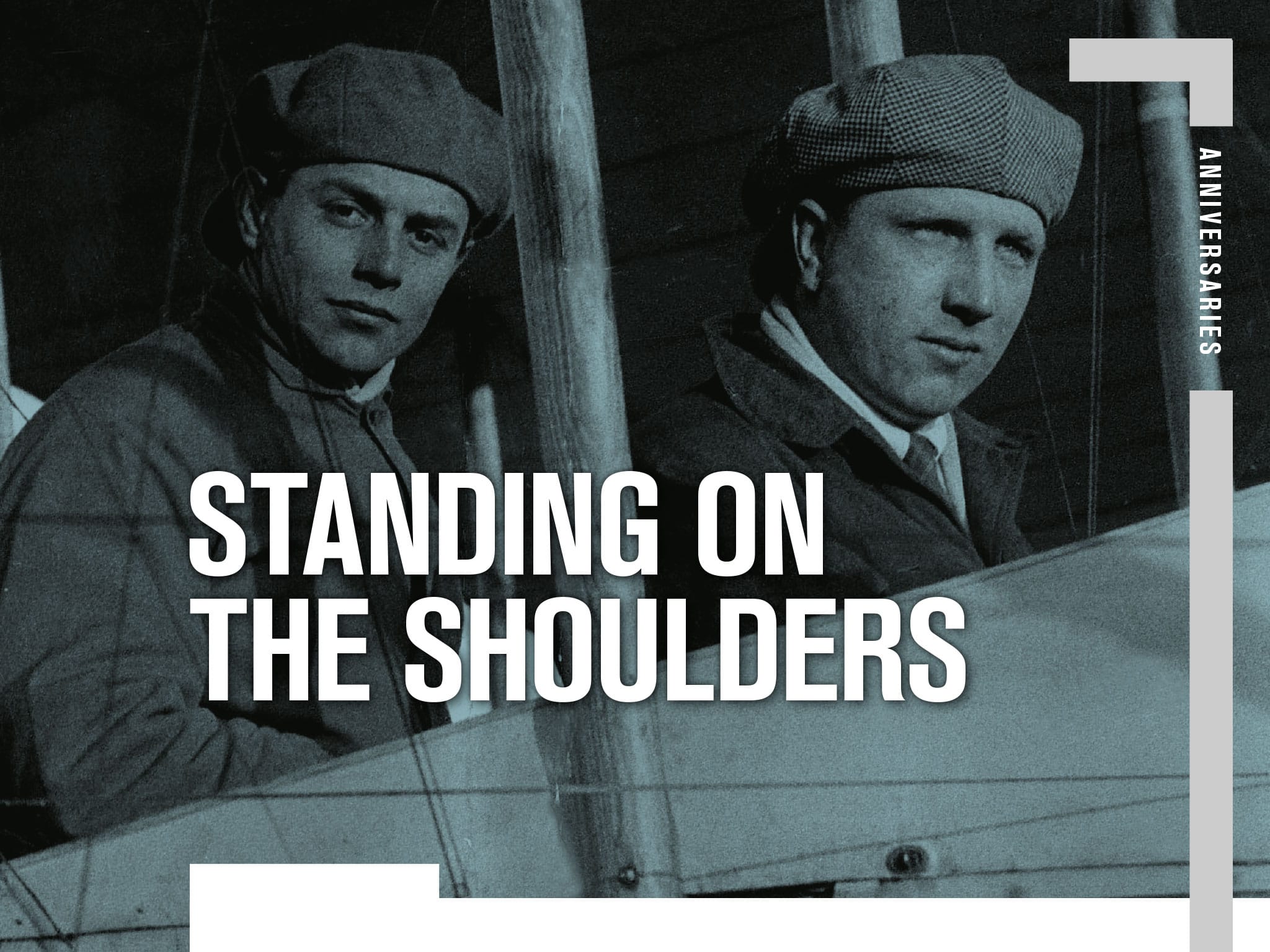

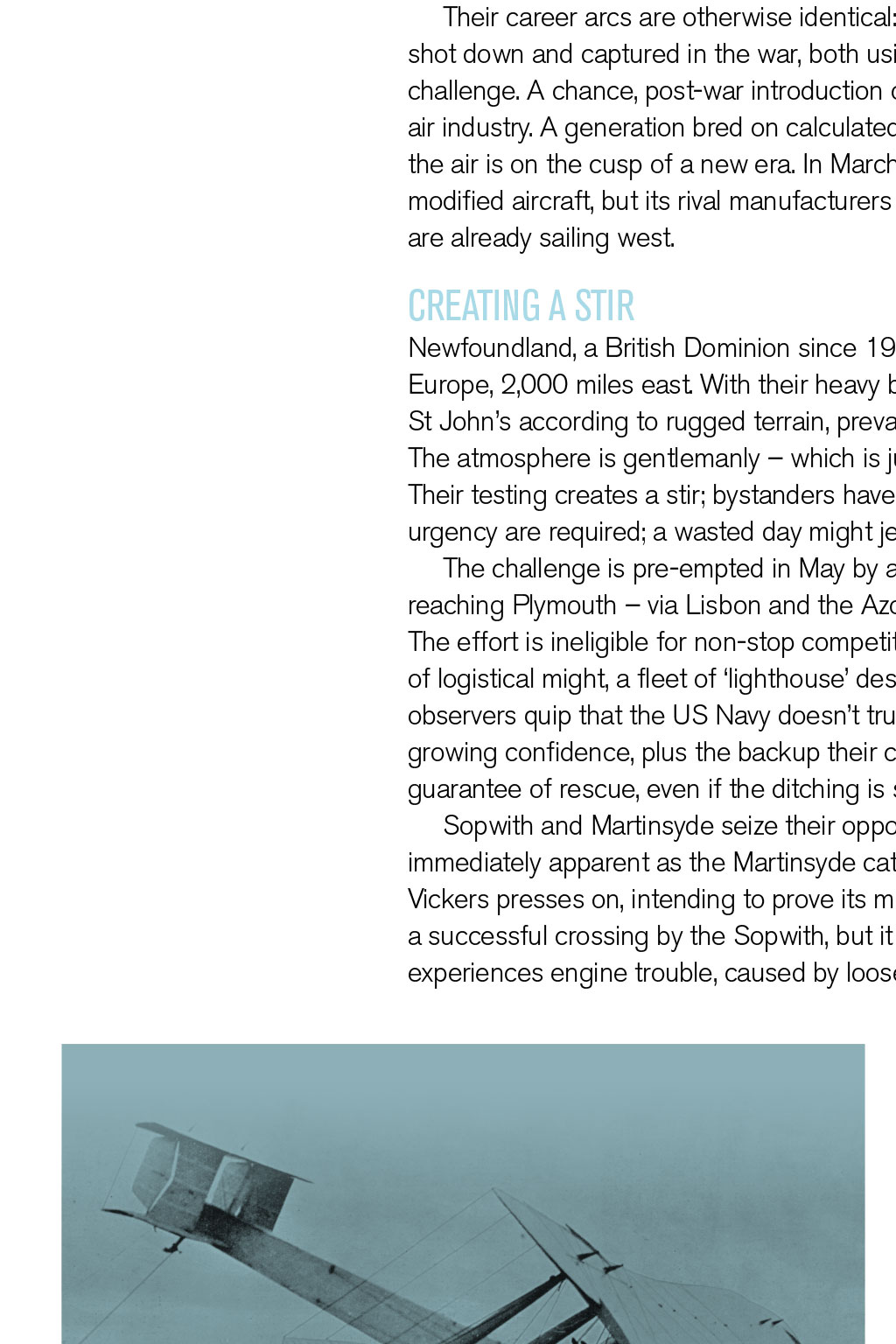

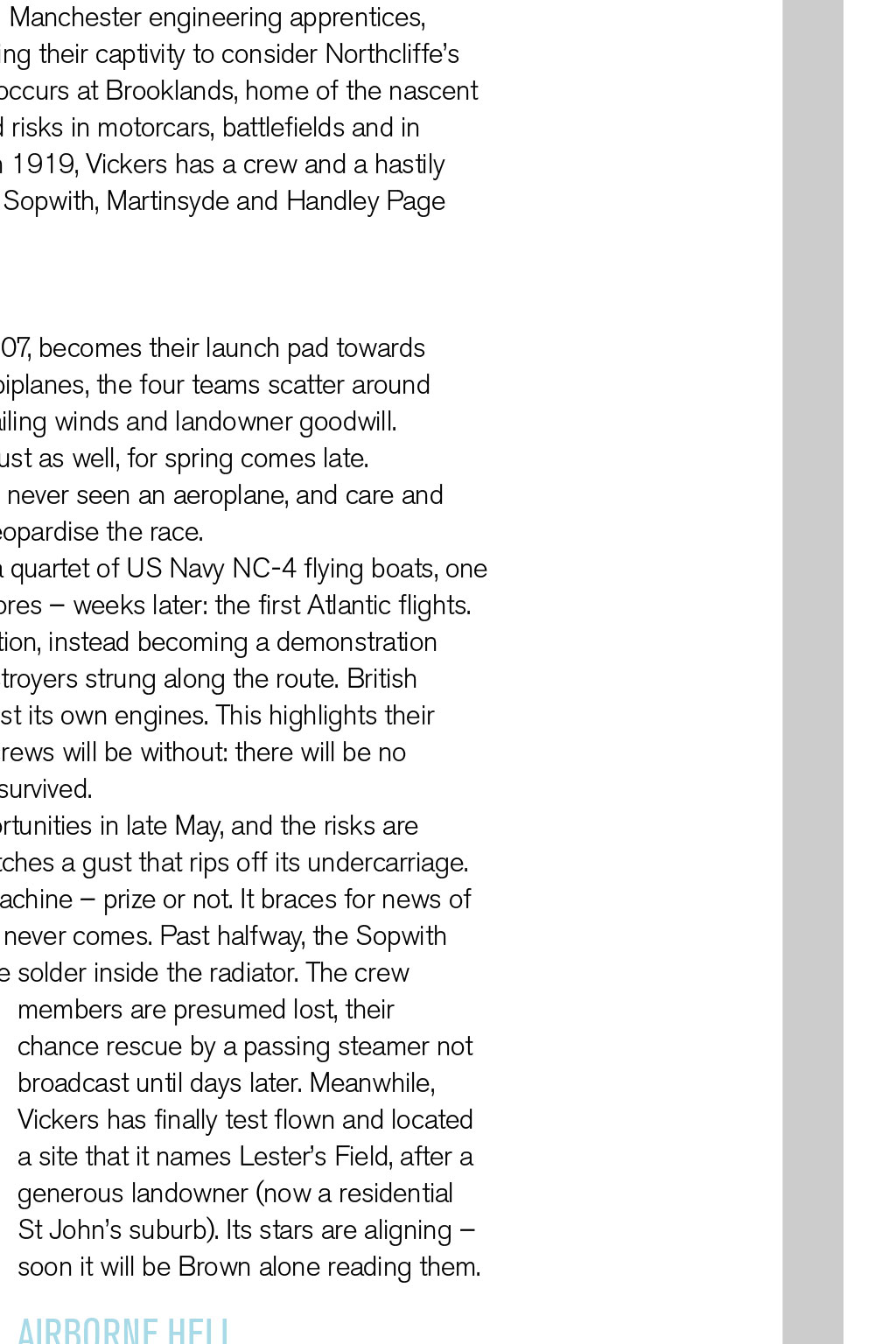

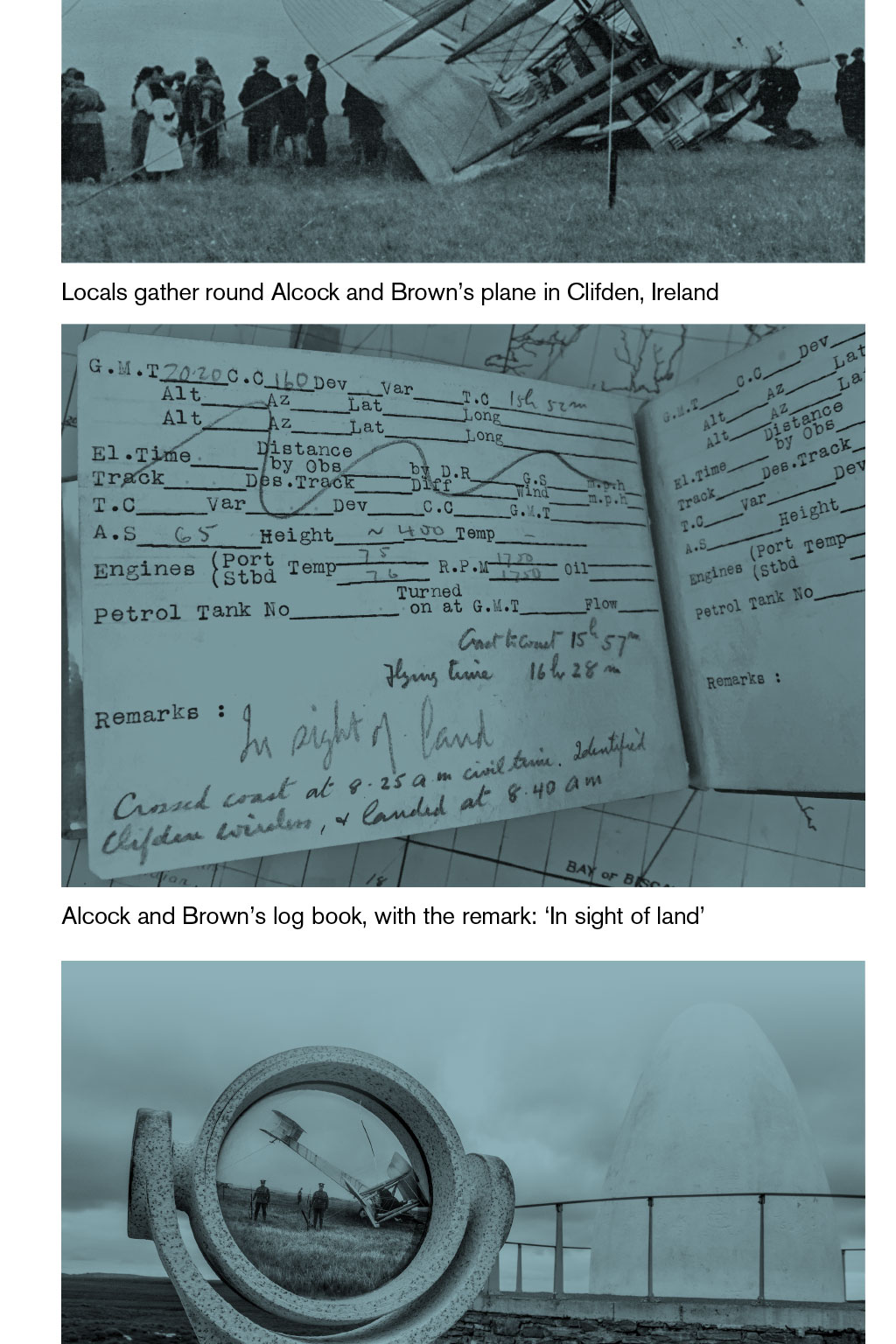

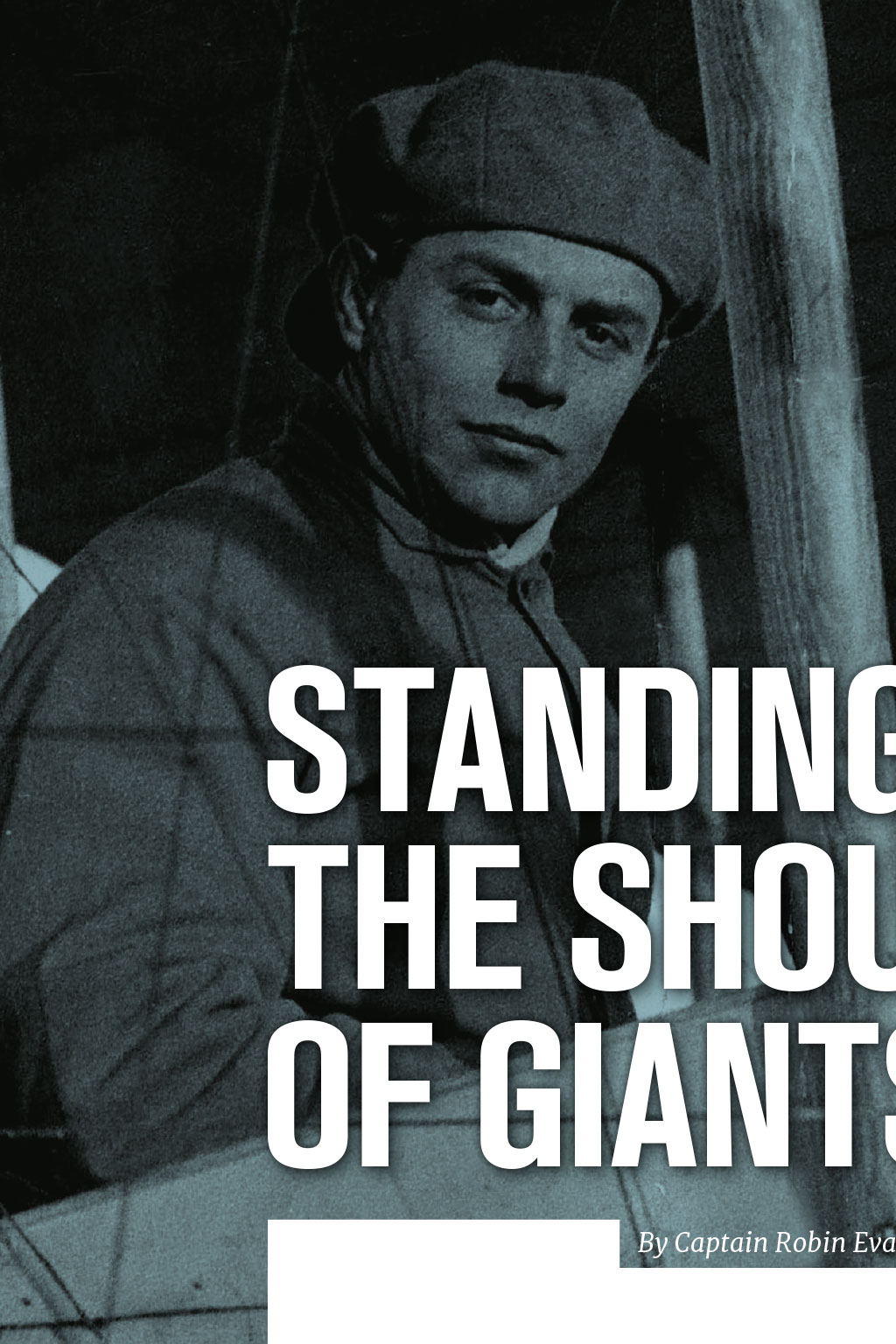

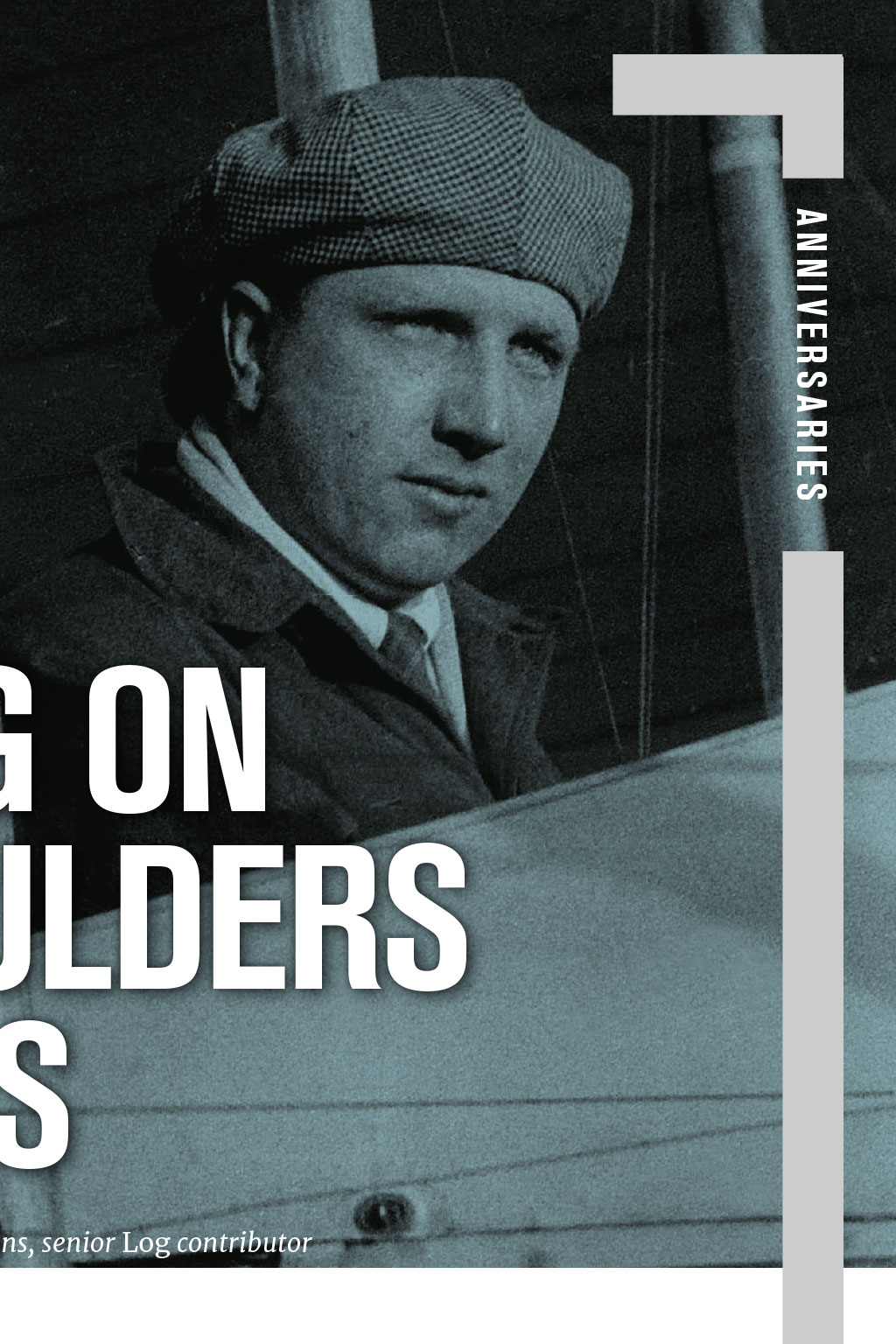

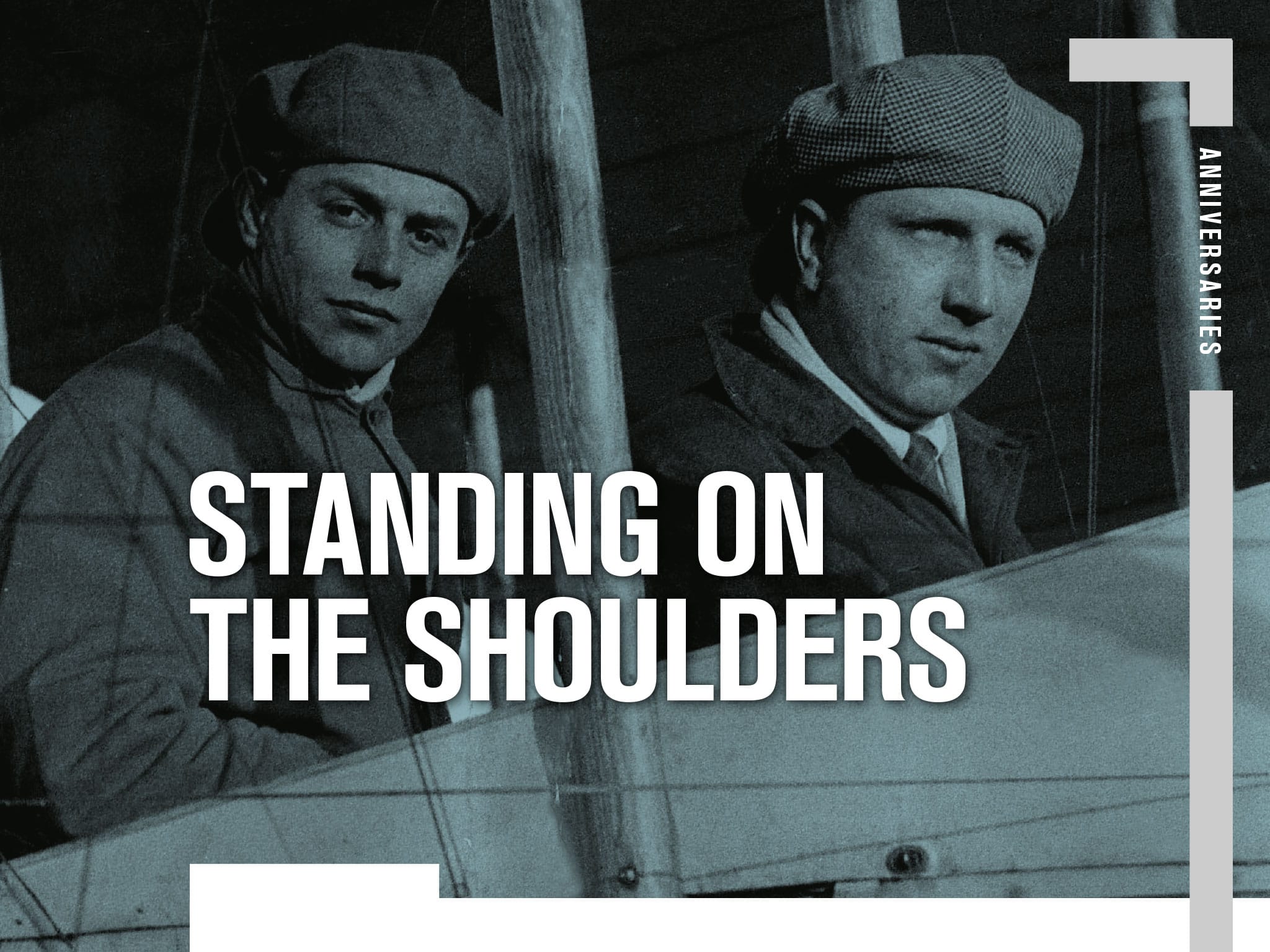

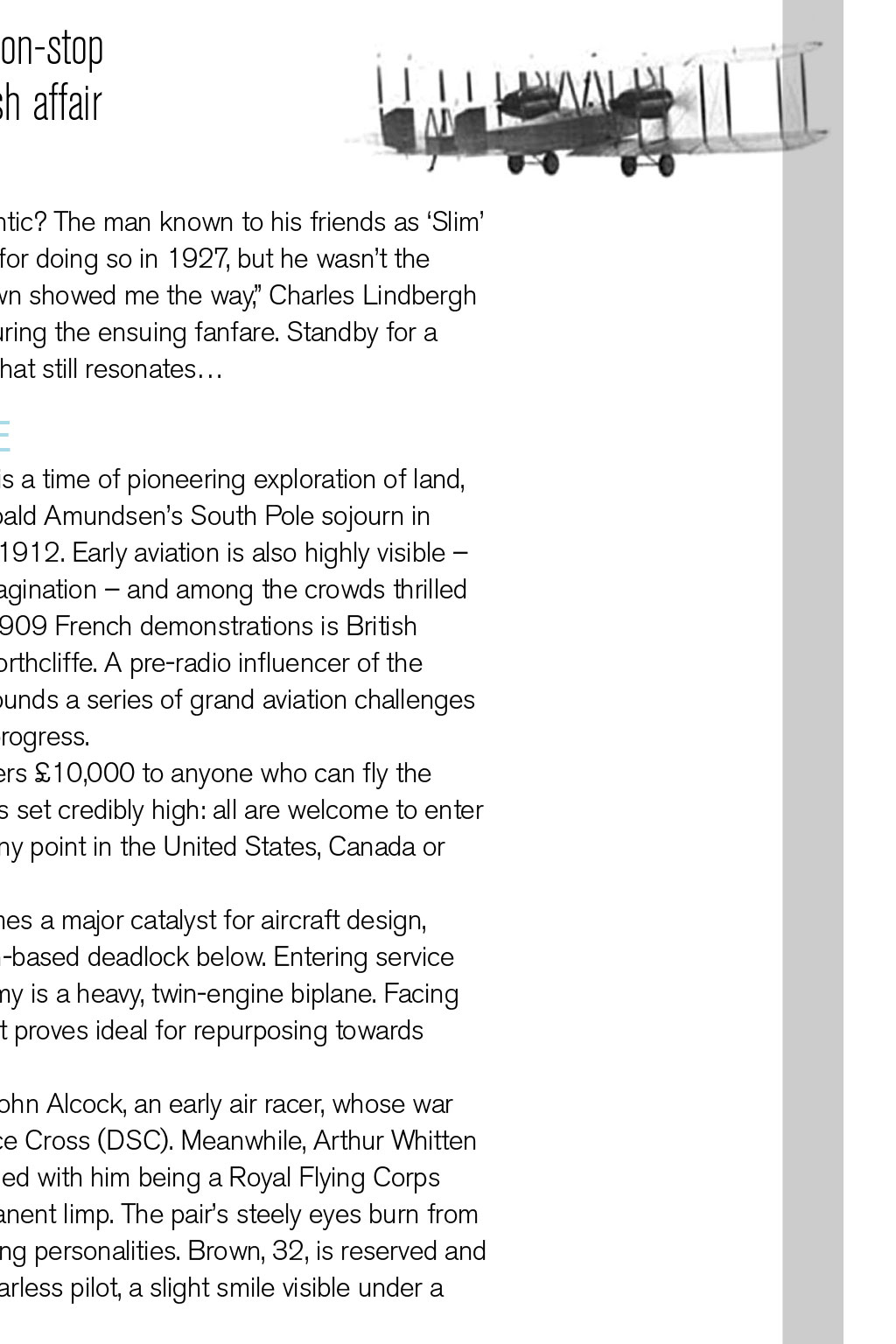

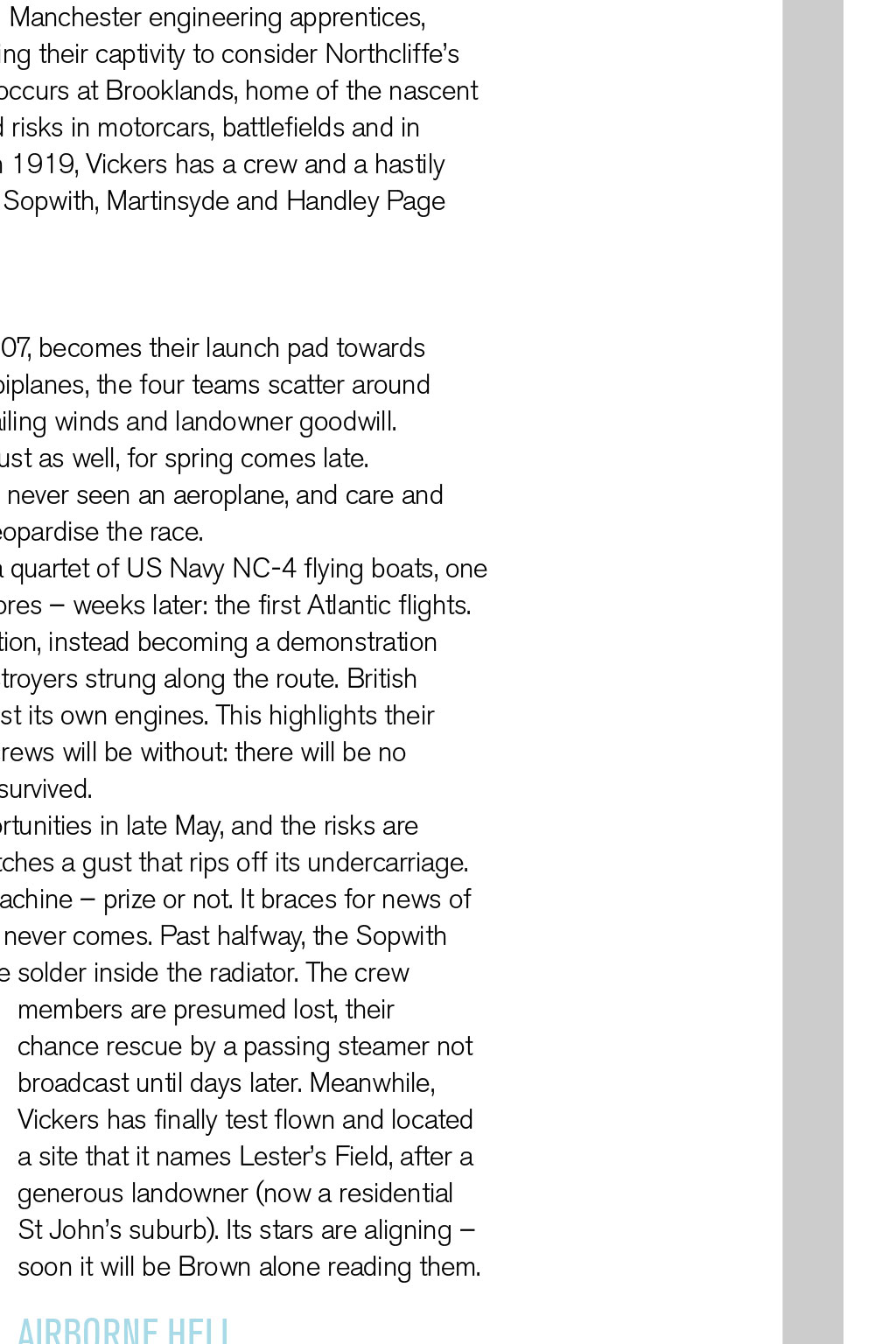

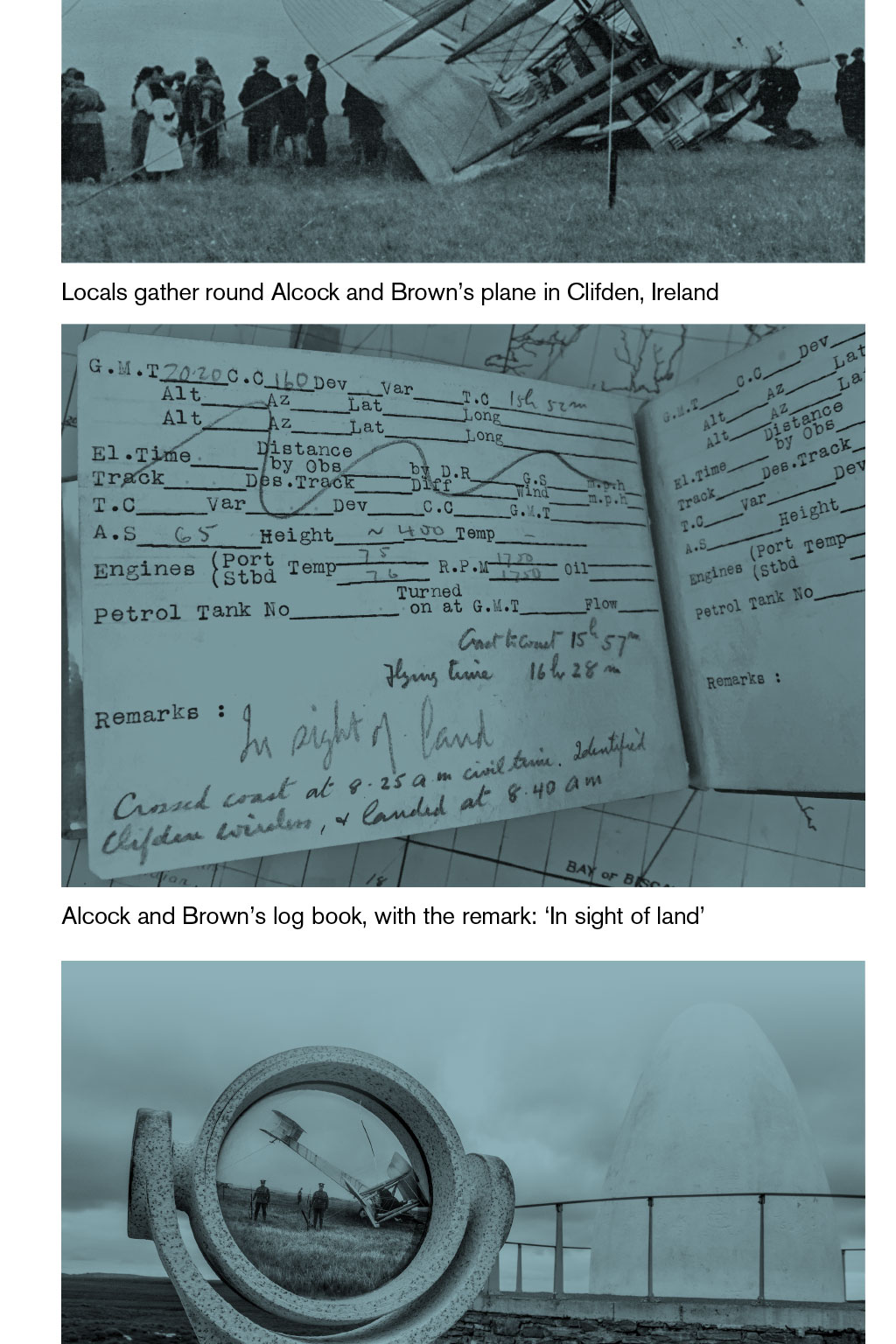

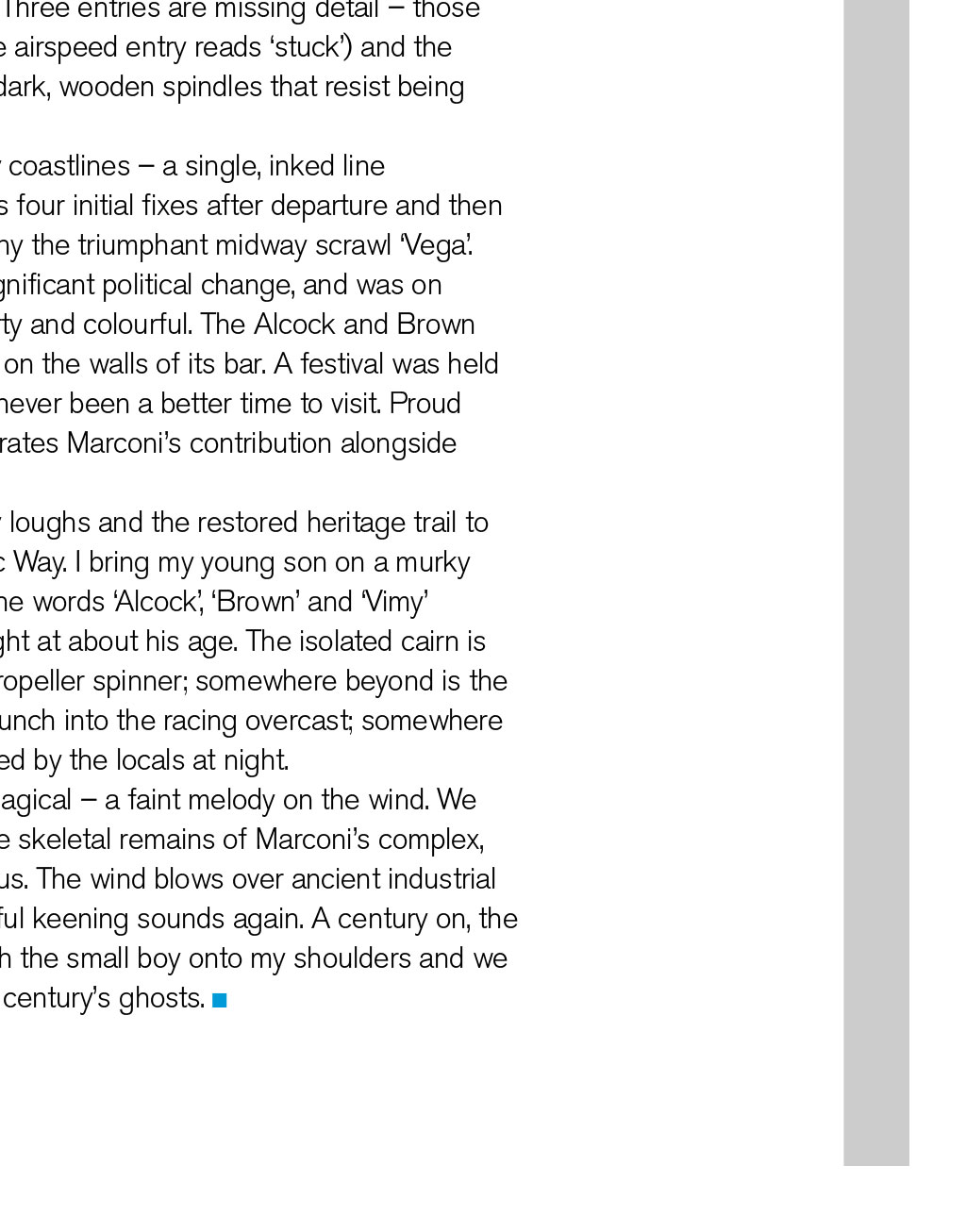

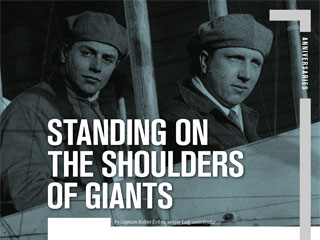

ANNIVERSARIES STANDING ON THE SHOULDERS OF GIANTS By Captain Robin Evans, senior Log contributor June is the centenary of the first non-stop transatlantic flight: a uniquely British affair ho first flew the Atlantic? The man known to his friends as Slim won the Orteig Prize for doing so in 1927, but he wasnt the first. Alcock and Brown showed me the way, Charles Lindbergh graciously declared during the ensuing fanfare. Standby for a primitive, unsung tale that still resonates LIGHTING THE FUSE The early 20th century is a time of pioneering exploration of land, sea and air, including Roald Amundsens South Pole sojourn in 1911 and the Titanic in 1912. Early aviation is also highly visible capturing the publics imagination and among the crowds thrilled by the Wright Brothers 1909 French demonstrations is British publishing tycoon Lord Northcliffe. A pre-radio influencer of the classes and masses, he founds a series of grand aviation challenges to stimulate aeronautical progress. In 1913, Northcliffe offers 10,000 to anyone who can fly the Atlantic non-stop. The bar is set credibly high: all are welcome to enter by connecting Britain and any point in the United States, Canada or Newfoundland. World War I halts competition, but becomes a major catalyst for aircraft design, which advances rapidly to loosen the trench-based deadlock below. Entering service to the conflicts final salvoes, theVickers Vimy is a heavy, twin-engine biplane. Facing up to business in the post-war depression, it proves ideal for repurposing towards endurance. Aware of the transatlantic challenge is John Alcock, an early air racer, whose war service earned him the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC). Meanwhile, Arthur Whitten Browns war began in the trenches and ended with him being a Royal Flying Corps observer; his injuries leave him with a permanent limp. The pairs steely eyes burn from the newsprint of the era, suggesting opposing personalities. Brown, 32, is reserved and studious; Alcock, 26, is the consummate, fearless pilot, a slight smile visible under a jaunty hat. Their career arcs are otherwise identical: Manchester engineering apprentices, shot down and captured in the war, both using their captivity to consider Northcliffes challenge. A chance, post-war introduction occurs at Brooklands, home of the nascent air industry. A generation bred on calculated risks in motorcars, battlefields and in the air is on the cusp of a new era. In March 1919, Vickers has a crew and a hastily modified aircraft, but its rival manufacturers Sopwith, Martinsyde and Handley Page are already sailing west. CREATING A STIR Newfoundland, a British Dominion since 1907, becomes their launchpad towards Europe, 2,000 miles east. With their heavy biplanes, the four teams scatter around St Johns according torugged terrain, prevailing winds and landowner goodwill. Theatmosphere is gentlemanly which is just as well, for spring comes late. Theirtesting creates a stir; bystanders have never seenan aeroplane, and care and urgency are required; a wasted daymight jeopardise the race. The challenge is pre-empted in May by a quartet of US Navy NC-4 flying boats, one reaching Plymouth via Lisbon and theAzores weeks later: the first Atlantic flights. The effort is ineligible for non-stop competition, instead becoming a demonstration of logistical might, a fleet of lighthouse destroyers strung along the route. British observers quip that the US Navy doesnt trust its own engines. This highlights their growing confidence, plus the backup their crews will be without: there will be no guarantee of rescue, even if the ditching is survived. Sopwith and Martinsyde seize their opportunities in late May, and the risks are immediately apparent as the Martinsyde catches agust that rips off its undercarriage. Vickers presses on, intending to prove its machine prize or not. It braces for news of a successful crossing by the Sopwith, but it never comes. Past halfway, the Sopwith experiences engine trouble, caused by loose solder inside the radiator. The crew members are presumed lost, their chance rescue by a passing steamer not broadcast until days later. Meanwhile, Vickers has finally test flown and located a site that it names Lesters Field, after a generous landowner (now a residential St Johns suburb). Its stars are aligning soon it will be Brown alone reading them. AIRBORNE HELL The weather remains capricious, and the Vickers team perseveres with the endless filtering of petrol and water. Saturday 14th June 1919 brings a marginal opportunity. Alcock and Brown load a cargo of sandwiches, coffee and chocolate, two soft toy cats Twinkletoes and Lucky Jim and a bag of specially Locals gather round Alcock and Browns plane in Clifden, Ireland franked airmail. The Vimy, adapted with extra fuel tanks, scrapes into the air to the cheering ofthe incredulous crowd. Their trials so far have been easy; now, testing his radio, Brown discovers it unpowered. Their flight suits also become unheated. Jammed side by side on a wooden pew, barely shielded from theelements, it will be an ordeal. Startled by a change in engine tone, they witness part of an exhaust fairing melting into the slipstream. They liken the sound of the unmuffled cylinders toarattling machinegun battery, and fiery tongues begin threatening the bracing wires. Adopting methods perfected since his wartime imprisonment, Brown uses Alcock and Browns log book, with the remark: In sight of land a carefully prepared chart, with star overlays and a marine sextant adapted with a spirit level. The elements will force him to revert to dead reckoning. The clamouring exhaust forces him to scrawl to Alcock: Dont be afraid of S, but we have had too much N already. Preoccupied with delivering unobstructed sun or stars, Alcock never releases the heavy controls. A piece of bracing installed to hold off the control forces is found to be unsuitable. Darkness falls, the world shrinking to their tiny cockpit, lit by the raging RollsRoyce Eagles. An epiphany: Vega and the Pole Star confirm position N50.7 W31.0 almost halfway. The night drones on, bringing lessons that resonate ominously. Attempting to climb through an angry layer, Alcock senses the ASI misbehaving. Hepossesses only a spirit bubble, compass and rudimentary altimeter, but bodily senses suggest enough and the Vimy tumbles into freefall. Atan extreme bank angle and suicidal altitude that leads both to taste salty air, Alcock regains a horizon. Sleet now chews at exposed flesh and builds on the Vimy. Brown, diligent with maintaining fuel flow, is unable to read the wing-mounted flow gauge overhead. Positive pressure keeps the carburettors supplied from a header tank in the upper wing. He rises from the cockpit bracing frozen, wounded limbs against the onslaught to wipe clear the flow gauge. Seeking clear skies, they climb through 10,000ft, but Alcock senses ice jamming the ailerons and descends back into cloud. The Vimy is increasingly nose-heavy. The fuel tanks one shaped as a rudimentary life raft are sequenced to keep the tail afloat in a ditching scenario. Watery daylight finally comes and they start a blind letdown. Alcock points: land! Brown has delivered magic. Intending to overflyGalway Bay en route to London, theyre approaching Clifden, 20 miles north of track. Clifden is silent; a Sunday morning in rural Ireland. Immediately south is Marconis giant wireless station, a hive of industry filling the air with the scent of burning peat. Shrouded mountains block their passage east, a single green patch beckoning from the rocky terrain below. Perhaps intoxicated by elation and fatigue, they dont question the frantic waves of the onlooking workers. Their 1,900-mile, 16-hour epic ends abruptly in the Derrygimlagh peat bog. Alcock remarks to the stunned locals: Yesterday, we were in America. Their transmission to the Royal Aero Club states: Vimy arrived Clifden 8-40 Machine damaged through landing in bog POST-FLIGHT LEGACY A dazed and deafened Brown makes the first observations of jet lag. A jubilant public awaits the modest heroes, Churchill awarding them their prize and George V, the KBE. But the reward is cruelly short. In December, Alcock departs Brooklands solo, for Paris, in a Vickers Viking. Outside Rouen, the weather deteriorates and he attempts a forced landing; a farmer discovers him with fatal injuries. This is a sledgehammer blow to Brown who also loses his only child during World War II and he dies of an accidental overdose in 1948. The repaired Vimy hangs in the Science Museum, a giant, cream ghost. Various artefacts can be found at Brooklands, including a replica Vimy that periodically runs engines. In 2005, this was flown by Steve Fossett in a re-creation of the same flight, his only concession a touchdown on 8A of the Connemara Golf Course. Further exhibits are on display at the RAF Museums and the Manchester Museum of Science and Industry. The Vimy proved itself inside a year by completing the triple crown to South Africa and Australia. It is soon repurposed as the Vimy Commercial with an enclosed cabin; several European flag carriers trace origins back to this era. The R34 airship completes the first return transatlantic crossing in July, and is considered by many as the future, until the explosive 1930s. By 1958, transatlantic passenger volumes by air exceed those of sea for the first time, as the Comet pioneers transatlantic operations. A century on, the idea of a two-crew heavy twin seems prescient. Also in 1919 came the Orteig Prize, bringing the Americans and French back into contention, and claimed eight years later by an outsider named Lindbergh. Why has his legend prevailed? Huge audiences in influential cities witnessed his 34hour fatigue-defying solo, their flag-waving hysteria drowning out the modest British reserve. Lindbergh also subsequently experienced notoriety when his infant son was kidnapped and murdered in 1932. In 1969, we were gifted the 747, Concorde and Apollo 11, but rewind 50 years from then and, heading east in darkness without forecasts, radio or navigation backup must have seemed as extreme as reaching the moon. No two humans had ever been as lonely or vulnerable, or forged such a popular path the worlds most contested airways. An Alcock and Brown statue sits outside the Heathrow Academy, within earshot of the Rolls-Royces spooling up on 27R, the scale of their feat at odds with their modesty. THEIR 1,900-MILE, 16-HOUR EPIC ENDS ABRUPTLY IN THE DERRYGIMLAGH PEAT BOG. ALCOCK REMARKS TO THESTUNNED LOCALS: YESTERDAY, WE WERE IN AMERICA TRANSATLANTIC WHISPERS Browns records, held in archive, reveal significant details by emphasised pencilpoint. Sixteen entries give hourly data, plus notes of constant cloud and acceptance of the inevitable drift in his dead reckoning. Three entries are missing detail those coinciding with the tumble from altitude (the airspeed entry reads stuck) and the obscured fuel gauge. His chart is rolled on dark, wooden spindles that resist being unfurled. A huge, sepia void separates two craggy coastlines a single, inked line connecting St Johns and Galway Bay. It has four initial fixes after departure and then nothing until heavy pencil strokes accompany the triumphant midway scrawl Vega. Connemara of 1919 was undergoing significant political change, and was on the verge of guerilla war; today, Clifden is arty and colourful. The Alcock and Brown hotel sits in a central position, the story told on the walls of its bar. A festival was held throughout centenary week, and there has never been a better time to visit. Proud of its adopted sons, the town museum illustrates Marconis contribution alongside Browns torch, flying helmet and boots. Immediately south lies a mosaic of peaty loughs and the restored heritage trail to all three, a signature site of the Wild Atlantic Way. I bring my young son on a murky evening to see what the place has to say. The words Alcock, Brown and Vimy were engraved in mind by a first book of flight at about his age. The isolated cairn is tasteful and shaped like a huge upturned propeller spinner; somewhere beyond is the unmarked landing site. Distant mountains punch into the racing overcast; somewhere between lies the notorious Bog Road avoided by the locals at night. Then something that seems eerie and magical a faint melody on the wind. We both turn, scanning for walkers: nothing. The skeletal remains of Marconis complex, destroyed in the unrest of 1922, lie before us. The wind blows over ancient industrial pipework, severed at ground level. The soulful keening sounds again. A century on, the site still resonates to those who listen. I hitch the small boy onto my shoulders and we begin the long walk home, thinking about a centurys ghosts.