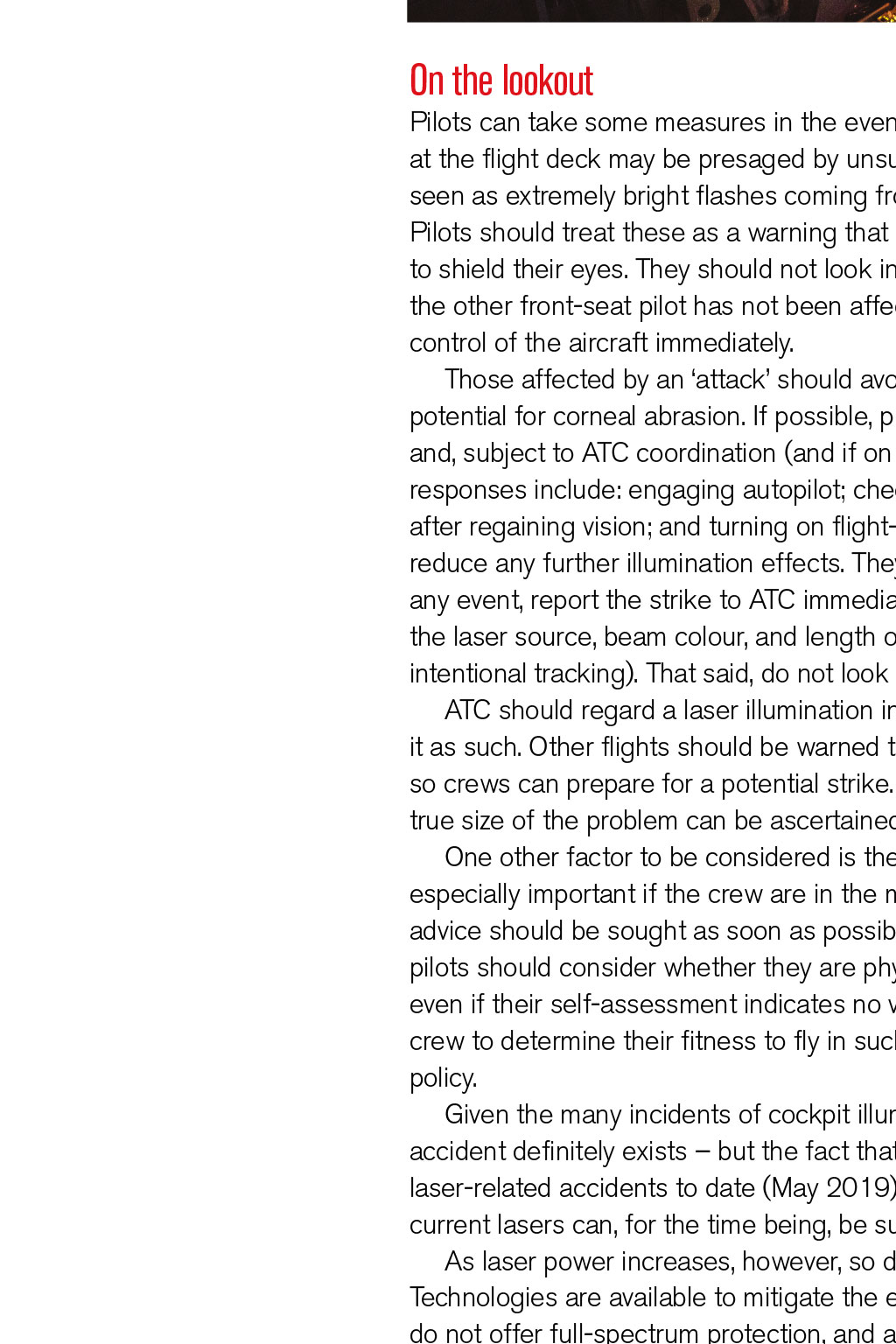

We examine the issue of lasers, and the strategies and technologies available to make the skies safer By Captain Martin Drake, BALPA NEC member he first reported laser attack on an aircraft in the UK was in 2004. By 2008, the number had risen to more than 200 and, since then, there have been about 1,500 attacks annually. Although this rate seems tobe falling in the UK, the worldwide figure is rising year on year. Pilots who have experienced a laser attack say its like a lightning strike, in that it is an instantaneous, very bright light, which is dazzling, distracting and can be disorientating. Aviation safety experts sayshining lasers into cockpits presents athreat to the entire aircraft. The first lasers were manufactured in 1960, by the Hughes Aircraft company, andwere based on research undertaken at the Bell Laboratories and Columbia University in 1958. When the first lasers went into production, they were said to be a solution looking for a problem to solve. Today, there are more than 55,000 patents involving lasers in the USA alone. They are truly useful pieces of technology for everything from engineering to medicine and navigation to data storage. It is doubtful those early laser developers could have anticipated their use in firework displays or their ability to drive cats to distraction. Power ranger Early lasers probably had a power of around one milliwatt (mw). Today, it is possible to buy lasers 6,000 times more powerful. Many countries have legislation and procedures that make it clear that shining alaser at an aircraft is not just an annoyance, but also aserious threat to the safety of theflight. They limit the power of pointers to an outputof 5mw, butenforcement hasproved to be more difficult than one would expect. Many incidents occur during take-off and landing, when pilots need to be most alert. It has been reported that pilots have had torelinquish control of their aircraft to the other pilot during such attacks. Law enforcement and emergency response aircraft responding to crime scenes have also had to terminate their flights because of laser interference. At first, the threat was played down by almost all nation states, regulators and operators; even warnings from professional pilots associations such as BALPA wereignored. How to counter the threat is a problem that has attracted the attention of scientists and engineers. Their considered opinion is that the best way forward is to limit the amount of light reaching the pilots eyes. This can be done in two ways: stopping the light entering the cockpit by adding filters to windscreens, or supplying pilots with special light-filtering spectacles. Much research has been carried out into preventing light ingression by applying afilmto the windscreens of aircraft andthere has been some success. Unfortunately, simple filters, coloured at the correct wavelength, also cut out a considerable amount of the light that pilots need to operate the aircraft safely, particularly at night. Interference filters are designed simply to cut out the wavelengths required. They have quite a narrow bandwidth in the order of a few nanometres so a large amount of ambient light is allowed to pass. If the laser light strikes the film just away from the design angle, however, it will pass through, and dazzle could still occur. This can be addressed by increasing the bandwidth, butthis would mean ambient light would also be restricted, and pilots would be in the same situation as with a simple filter. Current estimates suggest the light available to pilots would be reduced by 30%. Bearing in mind laser strikes tend to occur during the hours of darkness, this would be akin to wearing sunglasses at night. Then there is the question of future-proofing; as technology advances, it is possible that the wavelength of lasers could alter, so films would need to be tuned or replaced to combat new threats. There is also the issue of cost. Most developers are reluctant to put a price on their products, but current estimates are not too far away from $600 (470) per square inch. This would represent a huge expenditure to the industry for each aircraft. IT IS DIFFICULT TO FIND A SENSIBLE REASON FOR MEMBERS OF THE PUBLIC HAVING A POWERFUL, CLASSFOUR LASER. THEY ARE EXTREMELY DANGEROUS Quite a spectacle The alternative technology involves pilots wearing glasses, and a lot of work has been done in this area. Such equipment has been moderately effective for military and law-enforcement pilots, and the latest generation of glasses is a quantum leap forward from early attempts. For civil commercial pilots, however, spectacles bring several challenges, as they suffer from the same light-transmission issues as windscreen filters. In addition, they can and do remove some of the light transmitted from the electronic flight instrument systems (EFIS) that modern aircraft use. EFIS displays convey far more than just navigational information, and some elements of collision and windshear avoidance could be missed if they are not fully visible to the pilots. The concerns of commercial pilots about wearing spectacles when one does not need corrective lenses, or adding the laser-filtering glasses when one does, needs addressing in more than the cursory manner that has been displayed up until now. Other countries equivalents of trading standards can be very proactive in making sure lasers are imported and used for their intended purpose. Multifunctional, wireless laser, lecturing pointers made by reputable firms are well within allowable limits, and are highly unlikely to be a threat. Similar cheap copies, bought from certain internet sellers, tell a different story, as they are much more powerful and often incorrectly labelled. The importation and sale of lasers should be closely monitored and controlled. Education is essential. It is difficult to find a sensible reason for members of the public having a powerful, class four laser in their possession. They are extremely dangerous, and it is incumbent on governments, as some do, to give their citizens the knowledge to make informed decisions about laser ownership. Schools and colleges can be engaged, as can the social media of interest to parents. The police must be aware that a laser illumination event can be a safety hazard to aircraft, through effects such as: temporary vision loss associated with flash blindness a visual interference that persists after the source of illumination has been removed; after-image a transient image left in the visual field after exposure to a bright light; and glare obscuration of an object in a persons field of vision because of a bright light source located near the same line of sight. Someone pointing a laser at an aircraft is potentially endangering the flight. Legislation exists to prosecute offenders and should be used. On the lookout Pilots can take some measures in the event of an incident. A laser aimed successfully at the flight deck may be presaged by unsuccessful attempts to do so. These will be seen as extremely bright flashes coming from the ground and/or visible in the sky. Pilots should treat these as a warning that they are about to be targeted and prepare to shield their eyes. They should not look in the direction of any suspicious light. If the other front-seat pilot has not been affected, he or she should assume or maintain control of the aircraft immediately. Those affected by an attack should avoid rubbing their eyes, to reduce the potential for corneal abrasion. If possible, pilots should manoeuvre to block the laser and, subject to ATC coordination (and if on approach), consider a go-around. Other responses include: engaging autopilot; checking instruments for proper flight status after regaining vision; and turning on flight-deck lighting to maximum brightness and reduce any further illumination effects. They might also declare an emergency and, in any event, report the strike to ATC immediately. Include the direction and location of the laser source, beam colour, and length of exposure (flash, pulsed and/or perceived intentional tracking). That said, do not look directly into the beam to locate the source. ATC should regard a laser illumination incident as an in-flight emergency and treat it as such. Other flights should be warned that there has been laser activity in the area so crews can prepare for a potential strike. It is essential that pilots file a report so the true size of the problem can be ascertained, and resources directed appropriately. One other factor to be considered is the continuing health of pilots. This is especially important if the crew are in the middle of a tour of duty, when medical advice should be sought as soon as possible. If rostered for further flight sectors, pilots should consider whether they are physically and psychologically still fit to fly, even if their self-assessment indicates no visual impairment. It is for individual flight crew to determine their fitness to fly in such circumstances, regardless of operator policy. Given the many incidents of cockpit illuminations by lasers, the potential for an accident definitely exists but the fact that there have been only a minor number of laser-related accidents to date (May 2019) indicates that the hazard associated with current lasers can, for the time being, be successfully managed. As laser power increases, however, so does concern about potential outcomes. Technologies are available to mitigate the effects of lasers, but they are immature, do not offer full-spectrum protection, and are unlikely to be installed on airline flight decks in the foreseeable future. So, for now, the threat is most likely to be managed by the development and use of effective operational strategies, education, import controls, and taking offenders to court. TECH LOG LASER QUEST: THE FIGHT BACK