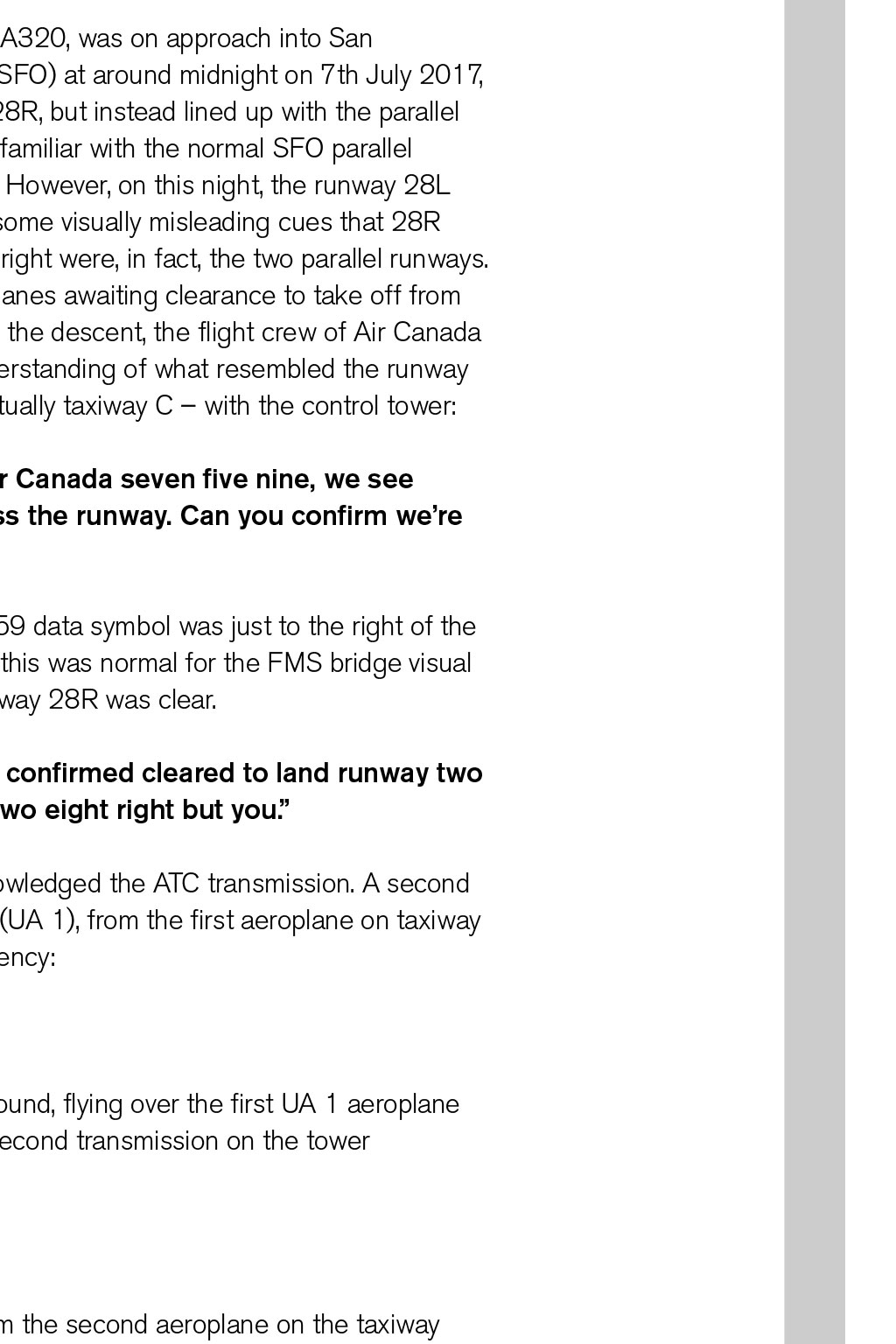

By Claire Coombes, BALPA Human Factors Scientist SHINING A LIGHT ON THE AIR CANADA NEAR-CATASTROPHE It was the near-catastrophe that could have resulted in the worst aviation disaster in history, with more than 1,000 people at imminent risk of death. In this article, we look at the NTSB’s description of the events of the taxiway overflight, and review the human performance factors and recommendations resulting from the incident Air Canada Flight 759, an Airbus A320, was on approach into San Francisco International Airport (SFO) at around midnight on 7th July 2017, and cleared to land on runway 28R, but instead lined up with the parallel taxiway C. The flight crew were familiar with the normal SFO parallel 28L/28R runway configuration. However, on this night, the runway 28L was closed and unlit, providing some visually misleading cues that 28R and the adjacent taxiway to the right were, in fact, the two parallel runways. On the taxiway were four aeroplanes awaiting clearance to take off from runway 28R. At around 300ft in the descent, the flight crew of Air Canada 759 questioned their visual understanding of what resembled the runway in front of them – which was actually taxiway C – with the control tower: AC 759: “Just want to confirm this is Air Canada seven five nine, we see some lights on the runway there, across the runway. Can you confirm we’re cleared to land?” The controller on duty noted that the AC 759 data symbol was just to the right of the centreline on their screen displays, but felt this was normal for the FMS bridge visual approach to runway 28R. Furthermore, runway 28R was clear. Controller: “Air Canada seven five nine confirmed cleared to land runway two Click to see the AC 759 incident aeroplanes on the taxiway by just 10-20ft vertical separation. The controller had also instructed ACA 759 flight crew to go around and, in the unfolding moments afterwards, advised ACA 759 flight crew that they had been lined up on the taxiway. The second approach to SFO was uneventful, with ACA 759 successfully landing on runway 28R. So, what human performance factors were at play here? Why did taxiway C so strongly resemble a runway to the pilots of ACA 759, and why was their course correction and go-around relatively delayed? NOTAMS To begin with, the flight crew were unaware – or could not recall information – of a runway closure at SFO. The NTSB report indicates that this pre-flight information was presented via NOTAM page eight of 27, and was the fourth line on the in-flight ACARS information. Pilots reading this will know the reality of pre-flight reviews of NOTAMs. They are not easy to digest, and there is often insufficient time to read and disentangle poorly described bits of information. This can place an intolerably heavy burden on crews to find ‘the needle in the haystack’ that is relevant to their upcoming flight, particularly when priority items may be buried under pages of other irrelevant items. eight right. There’s no one on runway two eight right but you.” At roughly 200ft, AC 759 flight crew acknowledged the ATC transmission. A second later, the captain of United Airlines flight 1 (UA 1), from the first aeroplane on taxiway C, made a transmission on the tower frequency: UA 1: “Where’s this guy going?” AC 759 had descended to 100ft above ground, flying over the first UA 1 aeroplane on the taxiway. The UA 1 captain made a second transmission on the tower frequency: UA 1: “He’s on the taxiway.” At about the same time, the flight crew from the second aeroplane on the taxiway C turned on their landing gear and nose lights, lighting up a section of the taxiway and the UAL1 plane in front. Around 89ft, ACA 759 flight crew initiated a go- around, descending to 60ft before climbing, narrowly clearing the second and third BOTH PILOTS’ UNDERSTANDING AND ACTIONS WERE CONSISTENT WITH HALLMARK FEATURES OF PERFORMANCE DECLINES ASSOCIATED WITH FATIGUE In this incident, the first officer did not recall a specific NOTAM about 28L closure, while the captain’s actions in lining up on the taxiway suggest that he did not recall that information. Hence, for this approach, both flight crew had the expectation of illuminated ‘normally configured’ parallel runways 28L/28R. Expectation bias and conflicting cues The captain and first officer were experienced and familiar with the SFO runway configuration. The captain had not experienced a previous occasion in which either runway had been dark, so both flight crew expected to see two illuminated parallel runways on their descent. While there would have been light cues coming from the taxiway, such as green (not white) centreline lights and taxiway in-pavement flashing guard lights, which differ to the surface of a runway, there were also a number of visually supporting clues that fed into taxiway C’s resemblance to runway 28R. Specifically, the navigation lights on the wingtips of the aeroplanes lined up on the taxiway partially resembled the runway edge lighting, while their flashing red beacon lights were consistent with features associated with approach lighting. Another supporting cue was the presence of runway and approach lights on the actual 28R, which would have appeared to the left of the pilots’ primary field of vision, and hence appeared to confirm they were correctly situated with respect to the normally adjacent parallel runway 28L. This expectation bias should not be understated – runway lighting aids are normally powerfully conspicuous features, but humans are vastly better at recognising salient features that ‘pop out’ than detecting missing features or slightly off-hue features, particularly under night-time conditions.. The NTSB analysis also notes that while a runway closure marker – a flashing white ‘X’ – was placed at the start of runway 28L, it would not have been in the flight crews’ primary field of view, and the flash rate (2.5 seconds on and off) may have been too slow to capture their attention unless they were looking in that direction. The flight crew from the preceding DA 521 flight into SFO, who were aware of the runway closure, also reported that the taxiway lights gave the impression that the surface could have been a runway, especially as no aeroplane shapes could be seen. So, even though their expectations were different – and they knew that runway 28L was closed – they, too, felt the taxiway could be perceived as a runway. Setting these visual features aside, normal cues that could have been provided from the backup lateral guidance (via the localizer) were missing for AC 759. When the first officer (pilot monitoring) had set up the approach, he did not manually tune the ILS frequency, and the captain either did not notice, or did not address this. Fatigue There were several reasons why fatigue was thought to have played a prominent role in this incident. First, both pilots had been continuously awake for an extended period of time, and they were landing precisely during the circadian lowest period of the 24-hour day-night cycle. The incident occurred at 23:56 local (02:56 for the flight crews’ normal body clock time). The captain, who was called from reserve, had been awake for more than 19 hours, and the first officer more than 12 hours. The captain had been assigned to the flight at 08:49 local (11:49 body clock) resulting in a notice period of 7 hours 51 minutes prior to report. The report also suggests an elevated workload factor contributed to the pilots’ fatigue, as they were dealing with thunderstorms during the first half of the flight and preparing for the approach during the second half. Both pilots’ understanding of the situation and actions were consistent with hallmark features of performance declines associated with fatigue. Increasing fatigue is associated with degraded information processing, deteriorating perception and memory, a narrowing of attentional focus and increased difficulty in overcoming ‘anchoring’ biases to a particular plan. Not much is known about how fatigue affects colour perception, but deteriorating binocular vision and ability to distinguish flashing from continuous visual signals is also an area of fatigue- driven decrement. Against this context, the NTSB concluded that the performance consequences of fatigue likely contributed to their ongoing expectation bias and delayed decision to go around. But why had both crew members been awake for such an extended period of time? The NTSB notes that “the flight crew’s work schedule for the incident flight complied with the applicable Canadian flight time limitations and rest requirements”. In fact, it goes further to state that the flight crew technically could have been on duty for 14 hours plus an additional three-hour extension because of the unforeseen operational circumstances that led to their delayed departure from Toronto. What has the reaction been? It should be noted that this flight-crew-initiated, low altitude go-around, was successful and prevented a serious collision. That said, the NTSB outlined some clear recommendations, including the need to review existing methods for presenting flight operations information to pilots both pre-flight and during flight, and develop ways to ensure they are optimised for pilot review. It was suggested that technical solutions alerting misalignment with a runway surface should be required for aeroplanes landing at primary airports within Class B and C airspace. With respect to fatigue, the NTSB concluded that Canadian regulations “do not, in some circumstances, allow for sufficient rest for reserve pilots”, leading to a recommendation for Transport Canada to revise regulations to address the potential for fatigue on reserve duties. However, NTSB Board member Bruce Landsberg was explicit: “If we expect solid human performance where lives are at stake, fatigue rules need to be based on human factors science and not on economic considerations.” From BALPA’s perspective, we hope this important message is received loud and clear. TECH LOG SHINING A LIGHT ON THE AIR CANADA NEAR-CATASTROPHE By Claire Coombes, BALPA Human Factors Scientist It was the near-catastrophe that could have resulted in the worst aviation disaster in history, with more than 1,000 people at imminent risk of death. In this article, we look at the NTSB’s description of the events of the taxiway overflight, and review the human performance factors and recommendations resulting from the incident