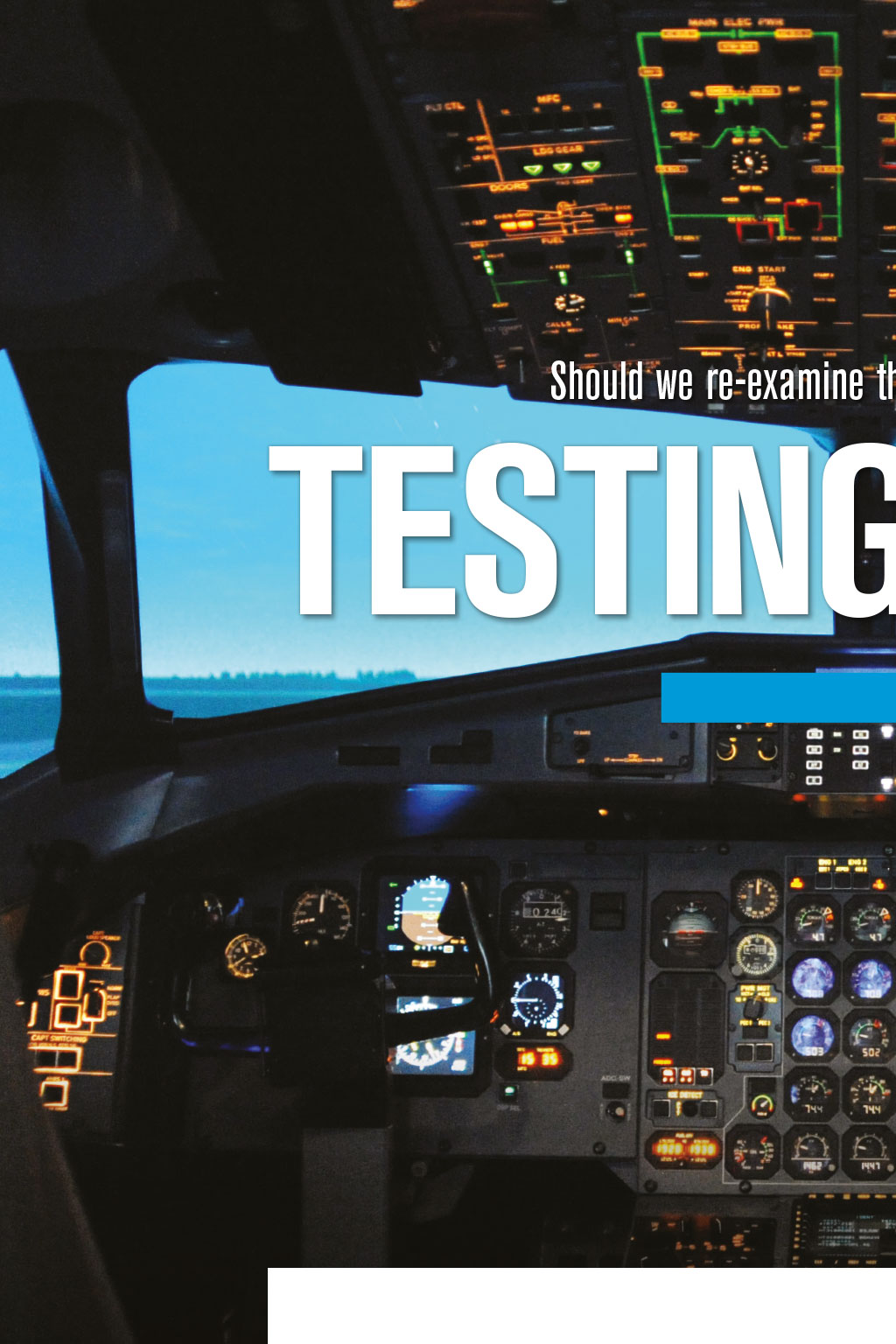

TESTING TIMES By Captain Paul Jarvis, Line Training Captain he regulatory requirements to which pilots are tested every six months were laid out a long time ago and, apart from increased use of automatics, have not kept pace with the rate of change of technology. We pack in set-piece regulatory manoeuvres such as V1 cuts, single-engine go-arounds, RTOs and LVOs into four-hour simulator details. The emphasis is on achieving a set standard of competence to comply with aircraft performance and certification standards, to prove we have maintained a stipulated level of competency to operate public transport aircraft under IFR. Accordingly, we have become experts for example, in single-engine aircraft control after V1. So much for the testing, but what about the training? A large part of the precious time spent in the simulator comprises tests repeated over and over every six months, at the expense of practising real-world skills that would equip us with the tools we need to cope with the complexities of modern aircraft. My contention is that we are monitored sufficiently in our day-to-day operation by automatic data gathering such as OFDM and ACARS. This gives our employers a vast amount of information on how we operate, and whether we have maintained our level of competency to operate public-transport class aircraft. With every noncompliance immediately transmitted by the aircraft, we are tested, if you like, every day we operate. We can even download flight parameters after each flight, to view as real-time simulations on our EFBs. This, in my view, is our coursework, through which our professionalism and level of compliance can be measured against a set standard, our accuracy and efficiency can be observed, and we can be held accountable every day we are at work. We are the most monitored profession so why do we have to perform a number of regulatory manoeuvres in the simulator that bear little relevance to the real-world challenges pilots can reasonably be expected to face? Facing up to the challenges Challenges presented by sensor failures, air data unit failures, spurious indications, display unit failures, air-ground logic failures, and multiple aural and tactile warning systems all present very different and confusing challenges but they form only a small part of our simulator sessions, to allow sufficient time for the V1 cut and the single-engine go-around. We need more time for teaching these confusing and non-intuitive, non-normal procedures, where we are dealing with interfaces laid down by well-meaning designers and regulators, with warning systems designed for safety, but which can overload us as we struggle to prioritise. For example, over-speed warnings combined with stick-shakers, or intermittent operation of trim systems or airspeed and AoA warnings, EGPWS alerts and aural callouts. These are currently given lip service while we continue to repeatedly fine-tune our skills at the V1 cut and the single-engine go-around. Whats in it for the airlines? Airlines will be reluctant to give crews additional simulator time, as this is expensive financially and in terms of crew availability. A cost-neutral solution can be achieved by reducing the testing requirement and increasing the amount of training within the current simulator slot allocation, which I believe will benefit all parties. WHY DO WE HAVE TO PERFORM MANOEUVRES IN THE SIMULATOR THAT BEAR LITTLE RELEVANCE TO THE REAL-WORLD CHALLENGES PILOTS CAN REASONABLY BE EXPECTED TO FACE? READ MORE By way of a debrief Whats in it for the pilots? Clearly, we all have to meet and maintain a defined standard, but the traditional simulator check can be stressful and fatiguing for an individual. I am aware of pilots who do not sleep well in the days before their recurrent checks, and of others who find it necessary to share their experience of the check itself and the foibles, idiosyncrasies and personalities of their examiners through social media. The benefit of non-jeopardy-driven training can only improve the engagement of pilots with the training system. By comparison, we all have to submit to an annual medical examination but if our weight, blood pressure and heart response was measured on a daily basis, this would no longer be necessary. Our health trends could be monitored continuously, as our engineers do with the aircraft systems. In terms of maintaining operational flying standards, our normal flying accuracy, fuel decisions, and even our response to nonnormal situations are monitored by the existing hardware every single time we fly. Current technology allows us to practise with a colleague in a fixed-base trainer as a crew. This could automatically record the necessary human-performance data, including our time to apply memory items, such as speed-brake and reverse thrust on an RTO, or the exact amount of rudder input applied on the V1 cut. A printout could be made available to the airline and ourselves if we wish without the need for a grizzled old examiner or some edgy wunderkind to sit behind us staring over our shoulder. Cheating could be avoided using fingerprint touch or facial recognition software. This could give us the opportunity to improve against a standard, if necessary. We can practise and practise, if we desire, until we achieve better than the required minimum standard and arrive at the training session with a certificate of achievement in our hands, in much the same way as we currently provide evidence of our systems and SOP knowledge through our e-learning. Whats in it for the regulator? The regulator has a great deal to gain, with less emphasis on a single test and more on day-to-day monitoring of crew, possibly combined with peer-group input. A pilots performance can be assessed more accurately; indeed, anyone can be an expert at the V1 cut or the engine-fire memory items, and gain top marks during the simulator check, but this expertise in no way affirms that the pilot is free from personal issues such as substance abuse, financial worries, marital breakdown, loss of sleep, fatigue or all of the above. Whats in it for the fare-paying public? It will have pilots who know the systems and the system architecture more fully, who understand the plethora of warning systems, and who are better trained. A crew faced with a situation such as confusing and contradictory warning systems illuminating or sounding simultaneously perhaps with unexpected aircraft-handling difficulties will clearly need to prioritise without becoming overloaded. More experience of these than is currently available in the simulator will enhance safety for the public and us. Whats in it for the manufacturers? Manufacturers will gain valuable feedback based on real pilot not test pilot interpretations of system and procedure knowledge, and checklist terminology. In my experience as a simulator examiner, I have often had to translate manufacturers lingua franca from the manuals into a language that line pilots can READ MORE understand. For example, one manufacturer thought it unnecessary to include generator Less time spent on regulatory switching in the external air source engine compliance, more time on learning start procedure, while another did not include More use of existing automatic the requirement to operate the start switch standards monitoring, giving us fewer for the APU-assisted airborne engine-start hurdles to jump procedure. In both instances, crews had real difficulty Better and more constructive relationships between the training in quickly adjusting to the failure of the systems to department and its clientele, with respond in the way that they had anticipated. By way of a debrief training better facilitated by removing the testing element Make the recurrent training more fun! This article represents the authors views alone, and does not necessarily represent the views of the authors employer, procedures, policies or practices. TR AINING Should we re-examine the way we examine?