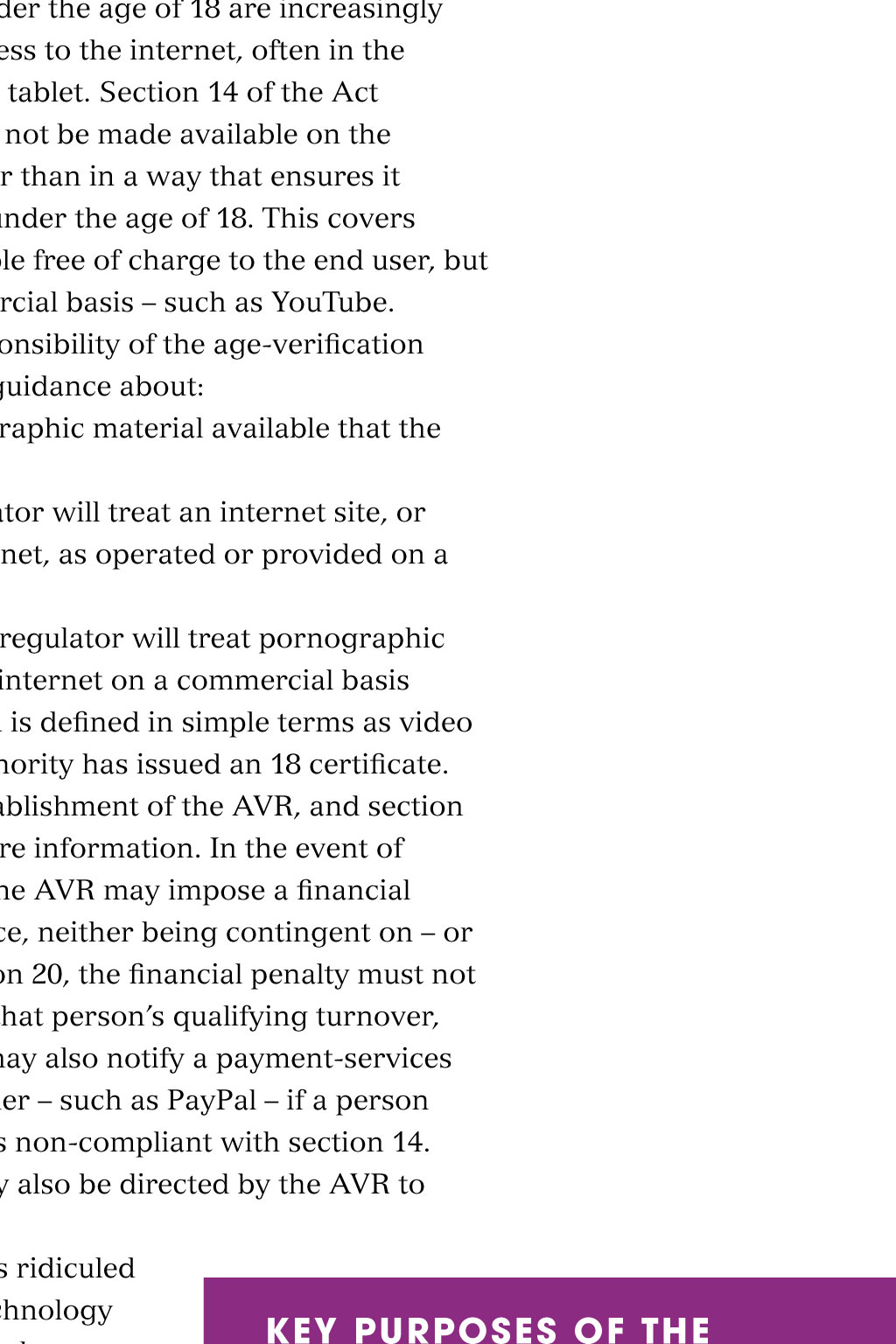

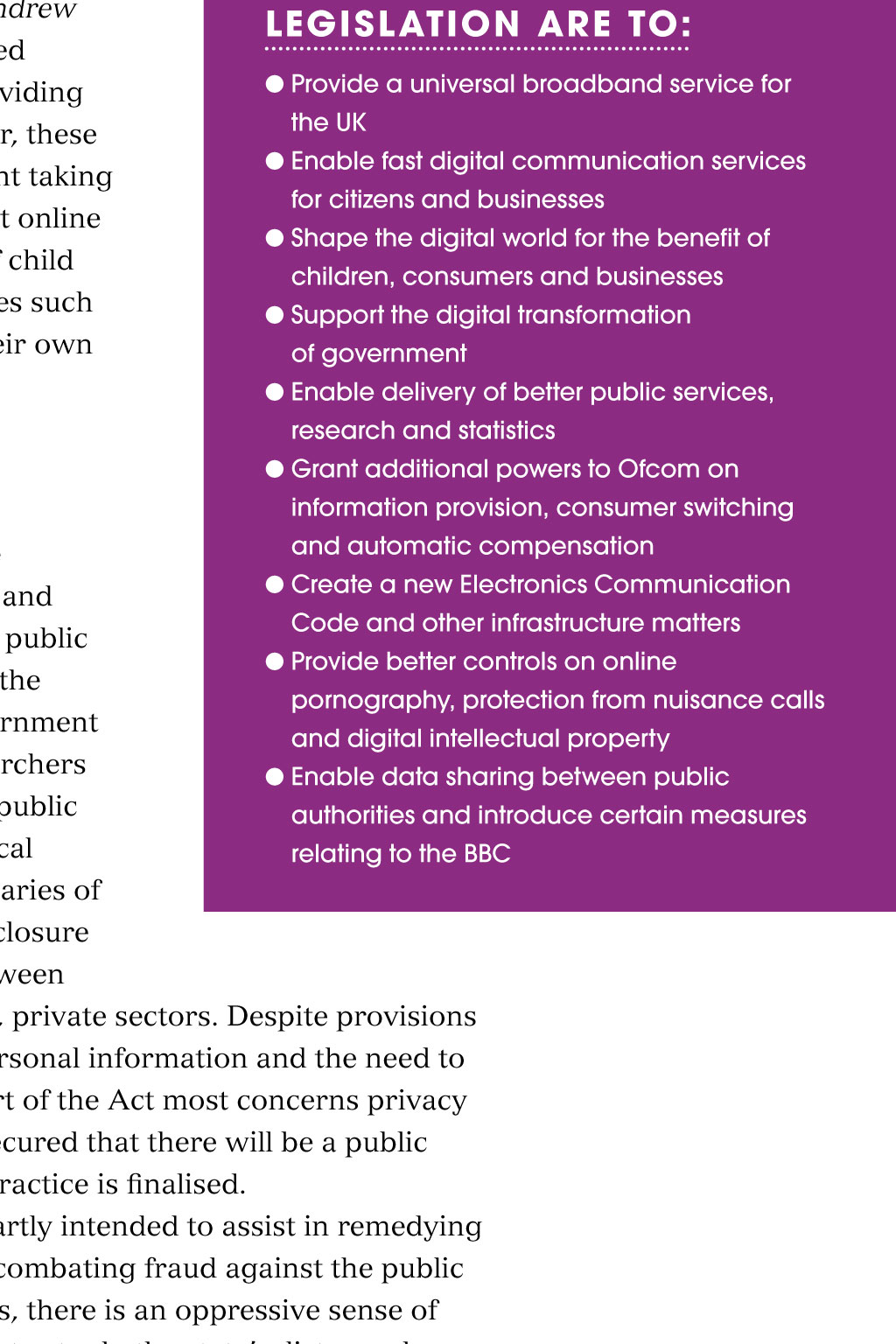

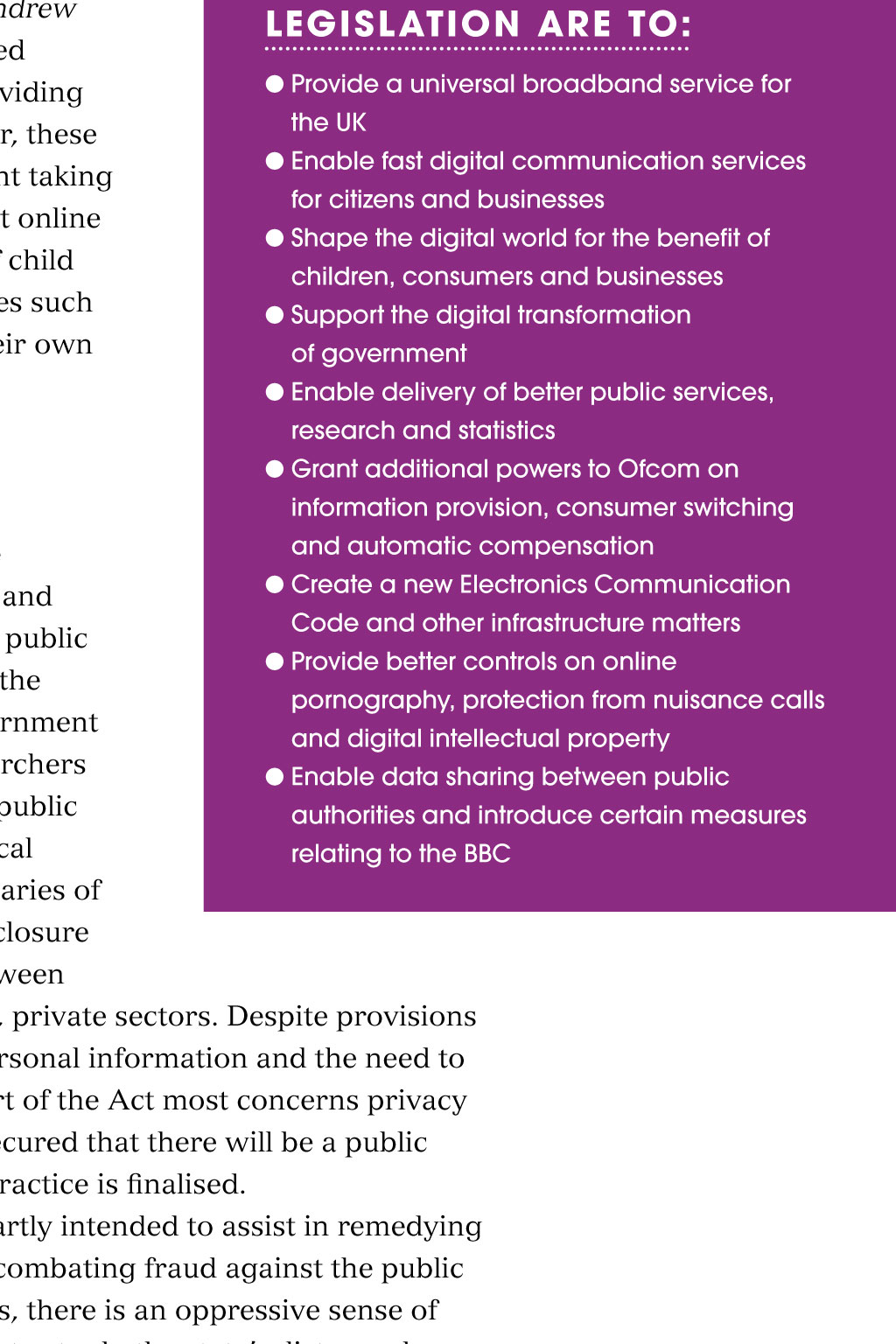

Legal perspectives on the Digital Economy Act 2017 In this feature l key purposes l child protection l digital government Championing the digital consumer? giles Bedloe considers benefits and concerns arising from the Digital Economy Act W hen it was debated in parliament, the Digital Economy Bill was not universally popular, with ever-present complaints from campaigners for civil liberties, privacy and data protection. But there is much in the Act for the consumer to cheer about. Few people would complain about the aims of the legislation (see box below), but will it deliver? While BT and its competitors wrangle with the industry regulator Ofcom over BTs stranglehold on the UKs digital infrastructure and level playing-field access consumers struggles with unreliable or weak broadband services can be forgotten. The Act sets out the Universal Service Broadband Obligation, promoting this concept from section 65 of the Communications Act 2003 to section 1. The aCt OF PaRLIaMENt download and upload speeds are specified, as On 27 April 2017, the Digital Economy Bill is fibre to the premises for every household received Royal Assent, and became law in in the UK by 2020. Regrettably, the Commons the United Kingdom as the Digital Economy rejected amendments made bythe House of Act 2017. This largely replicates changes Lords to the Universal ServiceObligation, so brought in by the 2010 Act of the same name. the commitment demanded of providers is Much of that Act was mothballed by the less than it might have been. Labour governments successors, but this The Upper Chamber favoured 30Mbps new legislation is likely to be implemented if by 2020 this is now a commitment to the Conservatives win the General Election 10Mbps by an unspecified future date. on 8 June. The majority of the provisions are Thecommunications providers will be to come into force either two months from required to pay compensation to the end the day on which the Act was passed, or on whichever day the Secretary of State appoints, user where they fail to meet the specified by regulations made by statutory instrument. standardsor obligations. This is all to be regulated by Ofcom. The disclosure and exchange of information between public and, in certain circumstances, private sectors, most concerns privacy campaigners Online pornography and child protection The Commons rejected amendments made by the House of Lords, so the commitment demanded of providers is less than it might have been Part 3 addresses an area of growing concern online pornography and childrens access to it. Those under the age of 18 are increasingly givenexclusive or unsupervised access to the internet, often in the convenient form of a smartphone or tablet. Section 14 of the Act requires that pornographic material not be made available on the internet on a commercial basis, other than in a way that ensures it is not normally accessible by those under the age of 18. This covers pornographic material made available free of charge to the end user, but via a platform operated on a commercial basis such as YouTube. Control over this is to be the responsibility of the age-verification regulator (AVR), who must publish guidance about: Arrangements for making pornographic material available that the regulator will treat as compliant Circumstances in which the regulator will treat an internet site, or other means of accessing the internet, as operated or provided on a commercial basis Other circumstances in which the regulator will treat pornographic material as being available on the internet on a commercial basis In section 15, pornographic material is defined in simple terms as video work for which the video works authority has issued an 18 certificate. Sections 16 and 17 deal with the establishment of the AVR, and section 18 gives the AVR the power to require information. In the event of contravention of sections 14 or 18, the AVR may impose a financial penalty or give an enforcement notice, neither being contingent on or exclusive of the other. Under section 20, the financial penalty must not exceed 250,000, or five per cent of that persons qualifying turnover, whichever is the greater. The AVR may also notify a payment-services provider or ancillary services provider such as PayPal if a person to whom the services are provided is non-compliant with section 14. Internet service providers (ISPs) may also be directed by the AVR to block access to material. Home Secretary Amber Rudd was ridiculed for her loose grasp of messaging technology kEY PURPOS ES OF tHE during an interview on the BBCs Andrew LEgISL atION aRE tO: Marr Show in March, when she talked Provide a universal broadband service for about encryption and tech firms providing the UK hiding places for terrorism. However, these Enable fast digital communication services provisions showing the government taking for citizens and businesses a tougher stance on ISPs and against online Shape the digital world for the benefit of content providers, in the interests of child children, consumers and businesses protection require global companies such Support the digital transformation as Google to do more to regulate their own of government content, and are to be welcomed. Enable delivery of better public services, research and statistics Digital government Grant additional powers to Ofcom on information provision, consumer switching Part 5 is ambitiously entitled Digital and automatic compensation Government, and there are multiple Create a new Electronics Communication provisions relating to the disclosure and Code and other infrastructure matters exchange of information to improve public Provide better controls on online service delivery. It is suggested that the pornography, protection from nuisance calls sharing of citizens data across government and digital intellectual property departments, local authorities, researchers Enable data sharing between public and further afield will enable better public authorities and introduce certain measures services. The provisions allow for local relating to the BBC authorities to be agents and beneficiaries of such information exchange. The disclosure and exchange, however, is to be between public and, in certain circumstances, private sectors. Despite provisions catering for the confidentiality of personal information and the need to adhere to a code of practice, this part of the Act most concerns privacy campaigners. The House of Lords secured that there will be a public consultation before such a code of practice is finalised. The exchange of information is partly intended to assist in remedying debt owed to the public sector, and combating fraud against the public sector. While these are laudable aims, there is an oppressive sense of Big Brother engaging the private sector to do the states dirty work and it is not alarmist to suggest that law-abiding citizens may lose sleep for fear that some oversight or omission will prompt their energy provider to make a disclosure that results in a government investigation. This Orwellian nightmare grows as one reaches Chapter 5 of Part 5, which allows personal information to be disclosed for research purposes, subject to conditions requiring the protection of the identity of the person whose information is being disclosed. The Data Protection Act reigns supreme here, but the fear that these cumbersome provisions might be misused or misinterpreted is palpable. There is a tendency for the ostensible aims and objectives of these enactments to facilitate a wholesale licence for government intrusion. So much detail is still to be determined before certain aspects of the Act come into force, and the wholesale access to the data of private individuals remains some way off. In the meantime, less controversial elements of the Act will come into force, and should produce tangible benefits for consumers, in terms of internet safety and the quality and standard of service provision. COPYRIgHt INFRINgEMENt Part 4 updates criminal offences within the and rights-holders: (i) extend only to gain or loss in money, and intellectual property field, and section 107 (2a) A person (P) who infringes copyright (ii) include any such gain or loss whether (2a) of the Copyright, Designs and Patents in a work by communicating the work to temporary or permanent, and Act 1988 (CDPA 88) is to be replaced. The the public commits an offence if P (b) loss includes a loss by not getting original section reads: (a) knows or has reason to believe that P is what one might get. (2a) A person who infringes copyright in infringing copyright in the work, and More akin to the terms of section 2 a work by communicating the work to the (b) either onwards of the Fraud Act, this removes public (a) in the course of a business, (i) intends to make a gain for P or another reference to the infringement being in or (b) otherwise than in the course of a person, or the course of a business, and focuses business to such an extent as to affect (ii) knows or has reason to believe that copyright infringement by publication prejudicially the owner of the copyright communicating the work to the public will on the financial consequences of the commits an offence if he knows or has cause loss to the owner of the copyright, or infringement. Furthermore, the maximum reason to believe that, by doing so, he is will expose the owner of the copyright to a penalty on conviction on indictment for infringing copyright in that work. risk of loss. the offence increases from two to 10 years. Similar amendments are made to section The replacement is much simpler and (2B) For the purposes of subsection (2A) 198 of the CDPA 88 infringing the making more accessible for regulators, offenders (a) gain and loss available right (illicit recordings). Credits Giles Bedloeis a barrister at Drystone Chambers. Images: istock.com / ktsimage To share this page, in the toolbar click on You might also like Hit them where it hurts April 2017