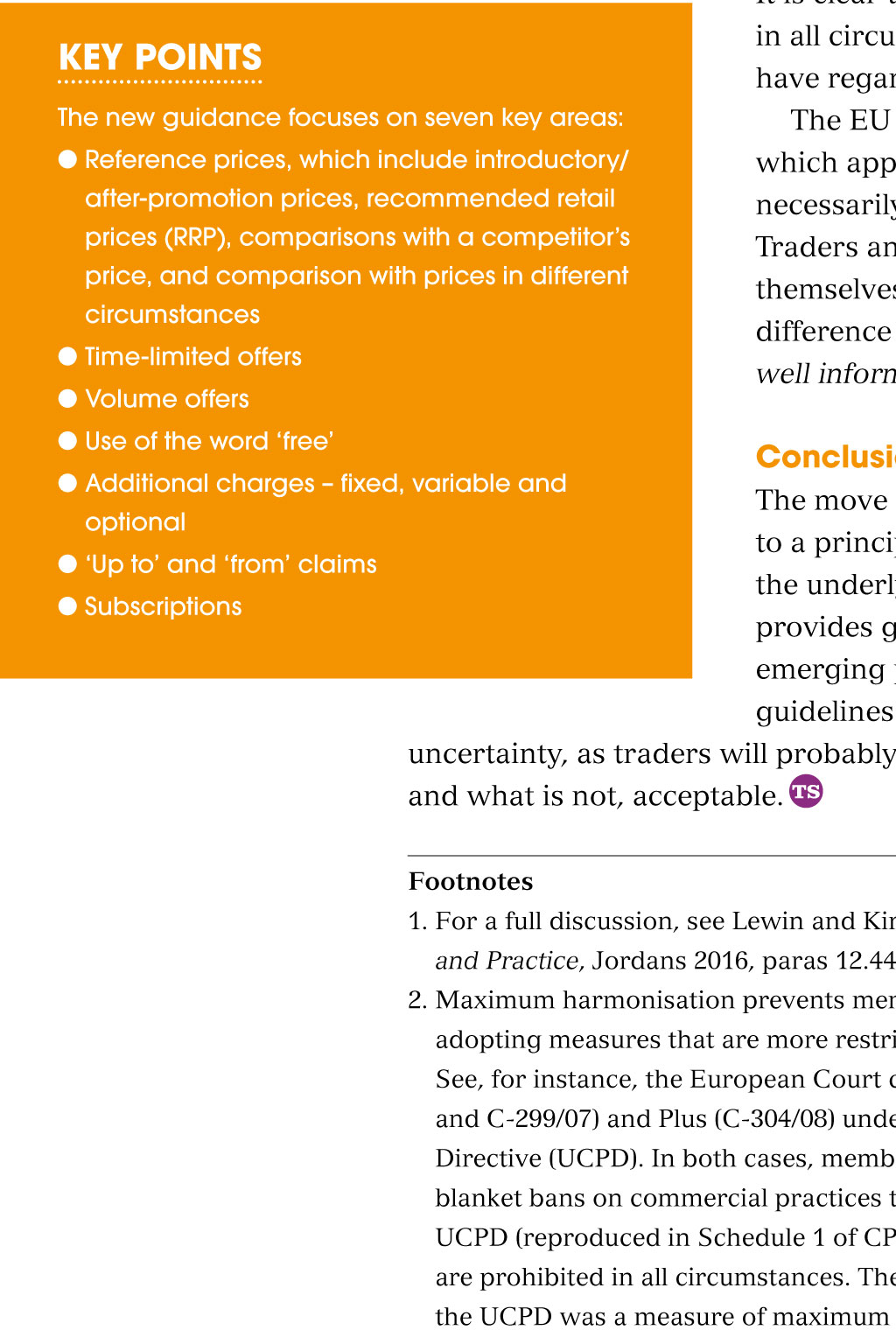

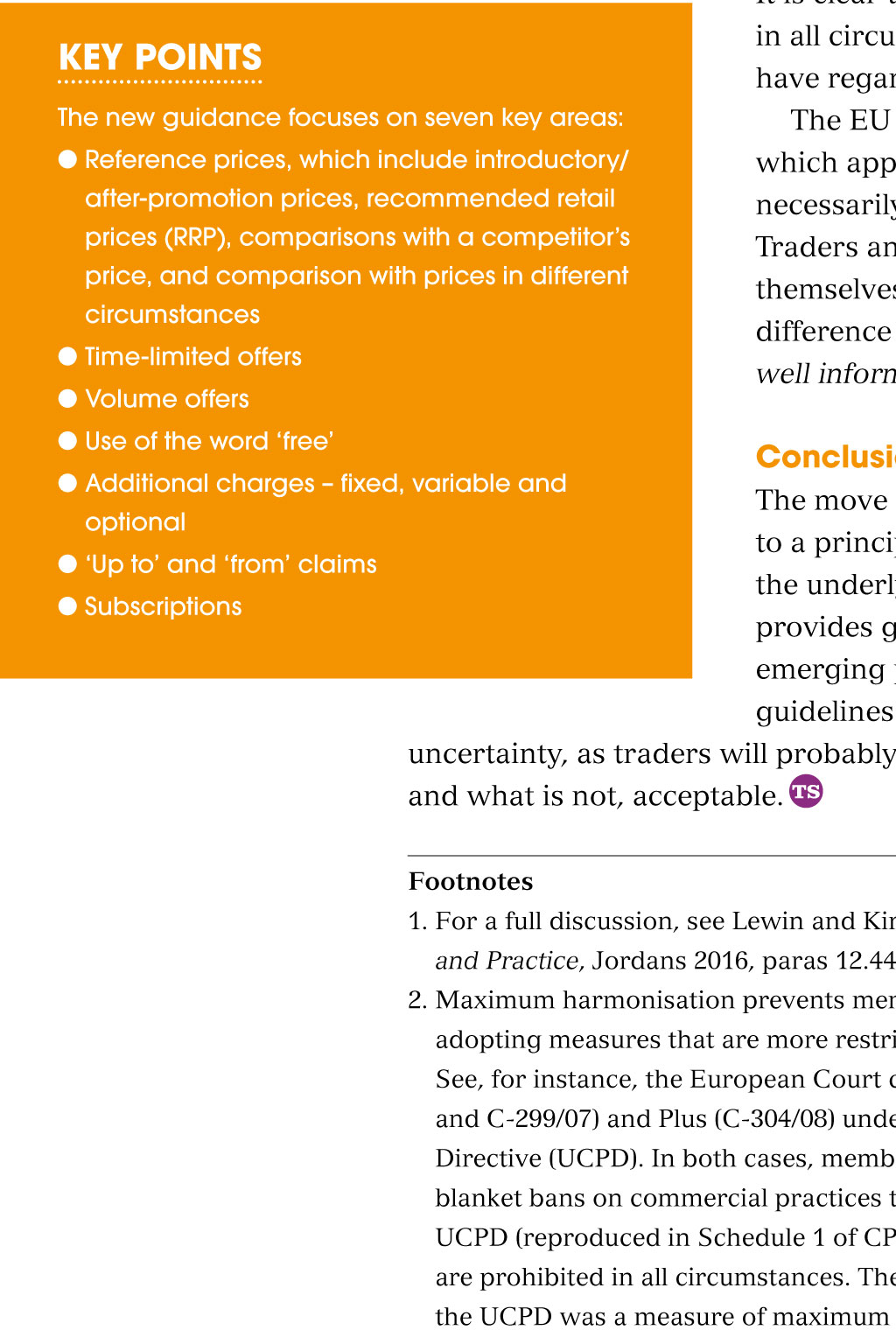

Legal perspectives: Guidance for Traders on Pricing Practices In this feature l living document l due diligence l key offers The price is right? CTSI published its much-anticipated Guidance for Traders on Pricing Practices in December. Anna Medvinskaia examines the history and status of this new document, as well as the most significant changes D A key criticism levelled at the BIS PPG during consultation was that it failed to keep pace with emerging commercial practices, legislative change and technological advances esigned to give helpful, common-sense advice, the Guidance for Traders on Pricing Practices replaces the 2010 Pricing Practices Guide. Such advice dates back to 1988, when the Code of Practice for Traders on Price Indications (Statutory Code) was approved by the then secretary of state. It was made under section 25 of the Consumer Protection Act 1987, which provided for a Statutory Code of Practice on pricing. While contravention of the Statutory Code did not of itself create liability, breach of or compliance with the Code was admissible as evidence in enforcement proceedings. The Statutory Code was replaced by the Department for Business, Enterprise and Regulatory Reform (BERR) Pricing Practices Guidance in 2008 (BERR PPG), with the coming into force of the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 (CPRs). Unlike its predecessor, the BERR PPG was not a statutory code; the same was true of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) PPG, which replaced it. In 2013, CTSI was tasked with updating the BIS PPG, and a widespread consultation culminated in the new guidance. A key criticism levelled at the BIS PPG during the consultation process was that it failed to keep pace with emerging commercial practices, legislative change and technological advances. So the new guidance isa living document, which will be amended to reflect relevant changes. Traders have been given until April 2017 to comply with the guidance and it is likely that the next few months will be busy for retailers marketing and compliance departments. Status of the new guidance The new guidance states that its aim is to provide practical common-sense advice to traders so it does not set out a strict and comprehensive regulatory code. As it makes clear: This guidance is notstatutory guidance and a court is not bound to accept it. The decision on whether any particular pricing practice is unlawful remains to be judged by all of the relevant circumstances. This is a useful reminder to traders, some of whom relied too heavily on the principles contained in the BIS PPG, forgetting its non-binding status. In its consultation, CTSI described the BIS PPG as giving the appearance of safe harbours which the law does not provide. This is nolonger the case, as the prescriptive approach of the BIS PPG has been abandoned in favour of one based on general principles. Any guidance given by an executive agency on the meaning of legislation is subject to the general constitutional principle that the role of interpreting the law rests with the courts. But this does not mean the courts will ignore such guidance, which may be admissible in criminal or civil proceedings in certain circumstances. The admissibility of the new guidance will depend on the factual circumstances of the case in question and the courts will be guided by ordinary principles of evidential admissibility.1 It is likely that the new guidance will often be relied upon by defendants in criminal proceedings, in the context of thedefence of due diligence. Whats new? In some areas, the new guidance helpfully gives illustrative examples of practices that are more or less likely to be compliant. There are two key changes that are worth particular mention, however. The first is theabsence of the so-called 28-day rule; the second is the removal of a 10 per cent threshold for Up to X per cent off and From claims. The 28-day rule required a trader to market the goods at the higher reference price first, for a minimum of 28 days. It had its origins in the Trade Descriptions Act 1968 see section 11, which has since been repealed and proceeded to find its way into each pricing practices guide thereafter, albeit in diluted form. In its most recent incarnation in the BIS PPG it said that a price used as a basis for comparison should have been [the traders] most recent price available for 28 consecutive days or the new guidance was published by CtSI more (1.2.3(a)). on behalf of the Department for Business, The new guidance simply advises a trader Energy and Industrial Strategy (successor to consider a non-exhaustive list of factors, to the Department for Business, Innovation including: How long was the product on sale and Skills) and supersedes the 2010 BIS at the higher price compared to the period for Pricing Practices Guide. which the price comparison is made? Other factors include the significance of sales at the higher price, the location of outlets where price establishment took place, and intervening prices. The removal of the 10 per cent rule in the context of Up to X per cent off and From promotions represents another important departure from the BIS PPG. This stated (at 1.9.3): General notices saying, for example, half price sale or up to 50 per cent off should not be used unless the maximum reduction quoted applies to at least 10per cent of the range of products on offer at the commencement of the sale. By contrast, the new guidance requires the maximum reduction quoted for example, up to 70 per cent off to apply to a significant proportion of the products included in the promotion. While the approach of the new guidance represents a compromise on certainty, to the frustration of traders and enforcers alike, it is in accord with the underlying legislation. The CPRs which implement an EU maximum harmonisation directive require each case to be assessed on its own merits, unless the practice falls within the banned practices listed in Schedule 1.2 Accordingly, it is likely that any rigid code would be open to a legal challenge. The new guidance makes it clear there are no hard-and-fast rules and each factor for example, the duration of price establishment will need to be considered alongside others. This makes sense; a trader that markets goods at the higher price for a period of 28 days may well be non-compliant if no, or insignificant, numbers of sales are made at the higher price. Likewise, a trader that markets goods at the higher price for a shorter period may be deemed to be compliant if significant sales are made at that higher price. The underlying question will be whether the higher reference price is a genuine one, which must necessarily be a question of fact and degree. Similarly, any promotion that makes an up to or from claim will need to be genuine, to give a true overall picture of the price promotion. It is clear that 10 per cent will not be sufficient in all circumstances; it will be necessary to KEY poINtS have regard for consumer expectations. The new guidance focuses on seven key areas: The EU notion of the average consumer, Reference prices, which include introductory/ which appears in the CPRs 2008, will after-promotion prices, recommended retail necessarily form the basis of any assessment. prices (RRP), comparisons with a competitors Traders and enforcers will need to ask price, and comparison with prices in different themselves whether the practice will make a circumstances difference to a consumer who is reasonably Time-limited offers well informed, observant and circumspect. Volume offers Use of the word free Additional charges fixed, variable and optional Up to and from claims Subscriptions Conclusion The move away from a prescriptive approach to a principles-based one is in keeping with the underlying legislation and, arguably, provides greater flexibility to accommodate emerging practices. The lack of objective guidelines is, however, likely to create uncertainty, as traders will probably take differing views on what is, and what is not, acceptable. Footnotes 1. For a full discussion, see Lewin and Kirk, Consumer and Trading Standards: Law and Practice, Jordans 2016, paras 12.44 to 12.46. 2. Maximum harmonisation prevents member states from maintaining or adopting measures that are more restrictive than the harmonising measure. See, for instance, the European Court cases of Total Belgium (C-261/07 and C-299/07) and Plus (C-304/08) under the Unfair Commercial Practices Directive (UCPD). In both cases, member states had unilaterally introduced blanket bans on commercial practices that were not listed in Annex I to the UCPD (reproduced in Schedule 1 of CPRs), which sets out the practices that are prohibited in all circumstances. The European Court found that, because the UCPD was a measure of maximum harmonisation, member states were prevented from adopting more restrictive measures. If a practice was not in theAnnex, then it had to be assessed individually in light of the general clauses. The blanket bans were therefore found to be illegal. Credits Anna Medvinskaia is a barrister at Gough Square Chambers. Images: Polarpx / Shutterstock To share this page, in the toolbar click on You might also like Scheduling power January 2017