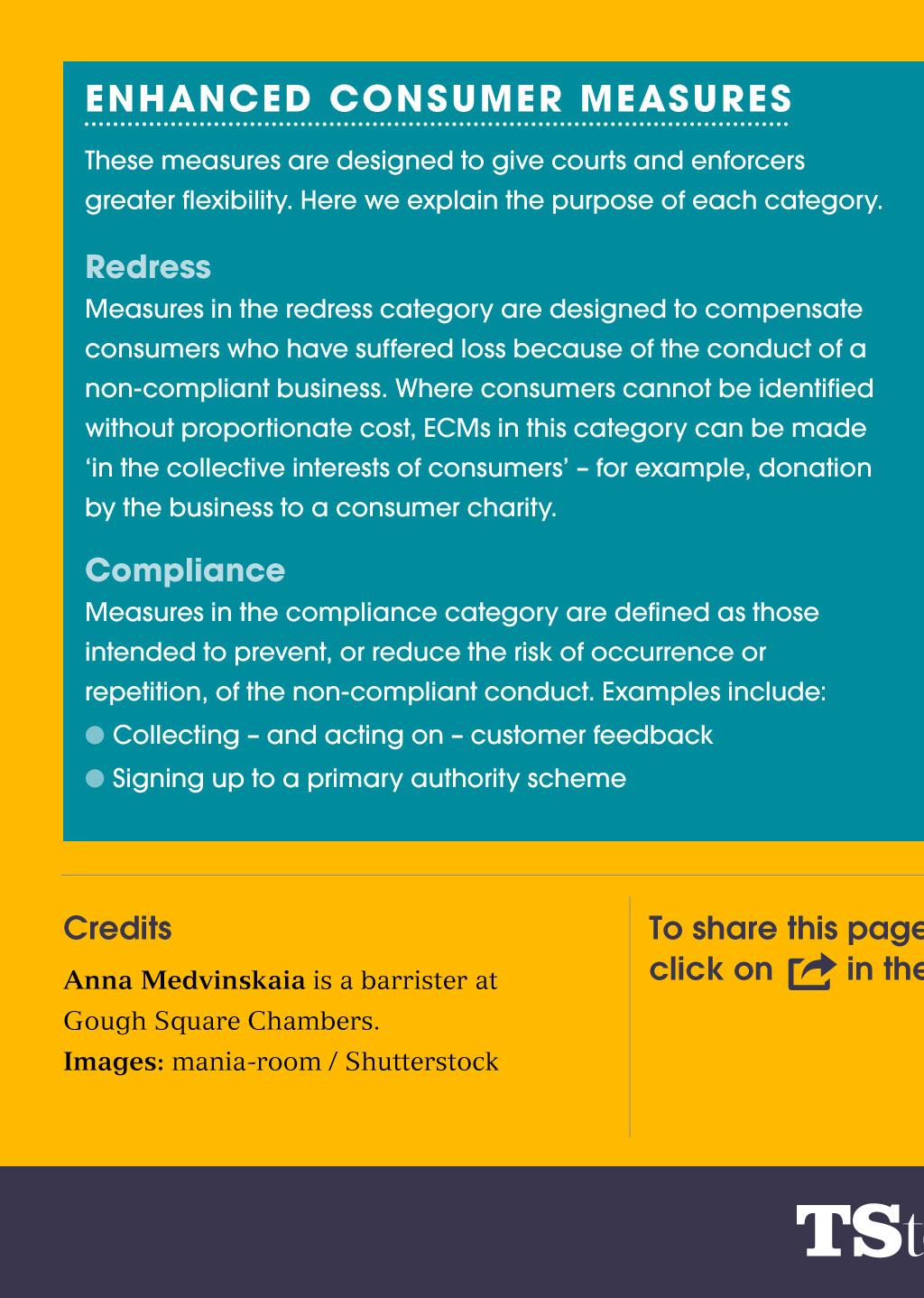

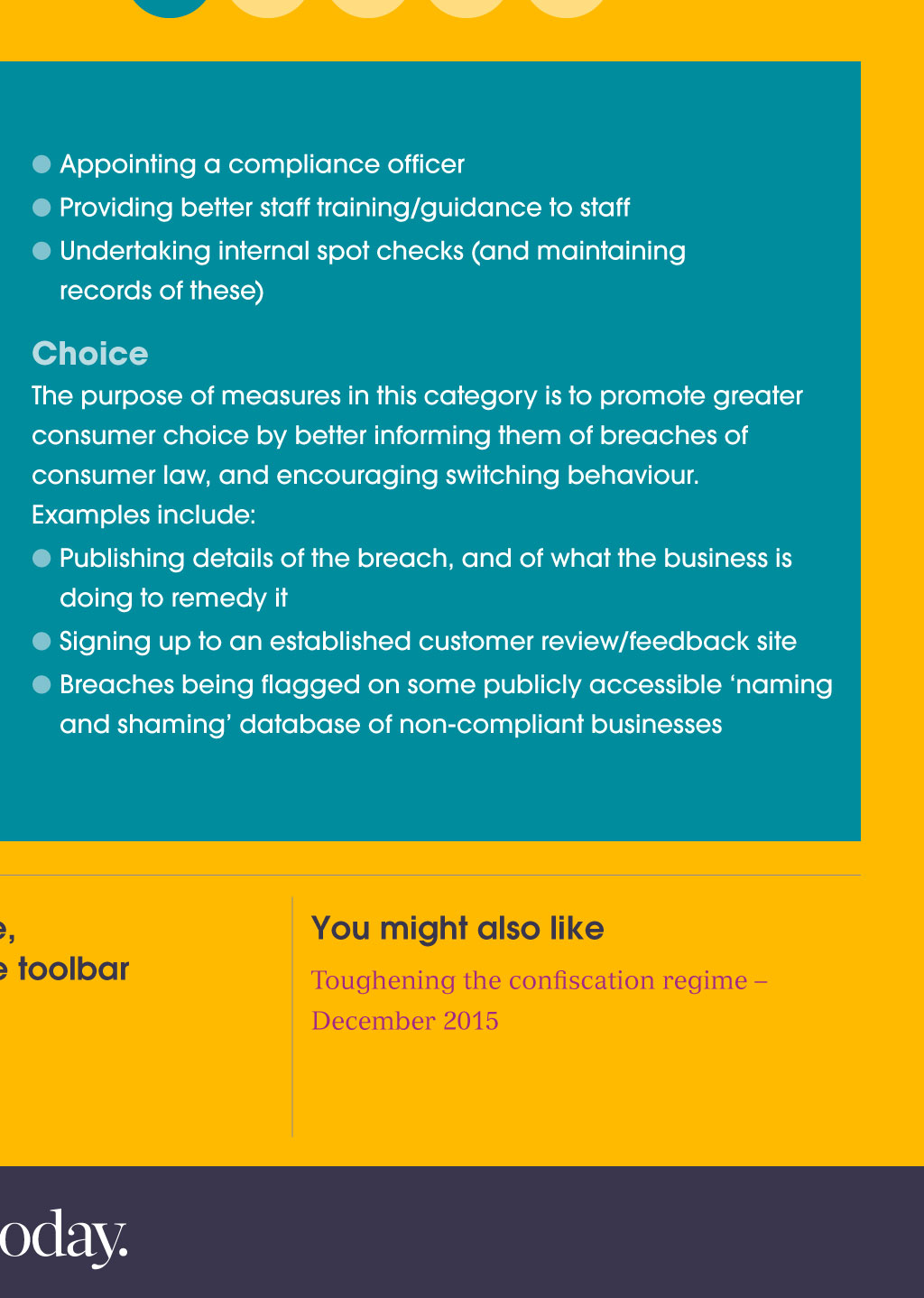

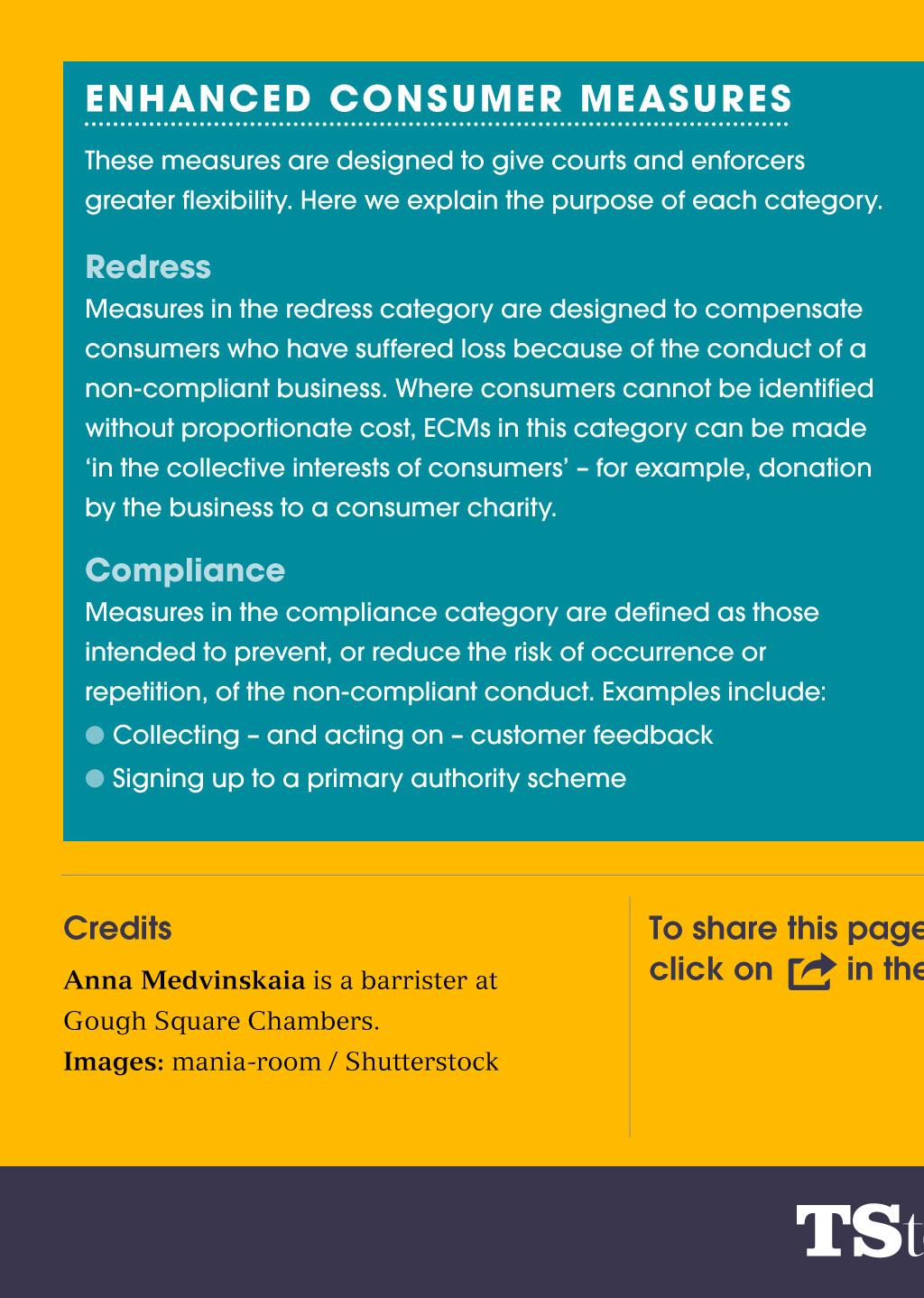

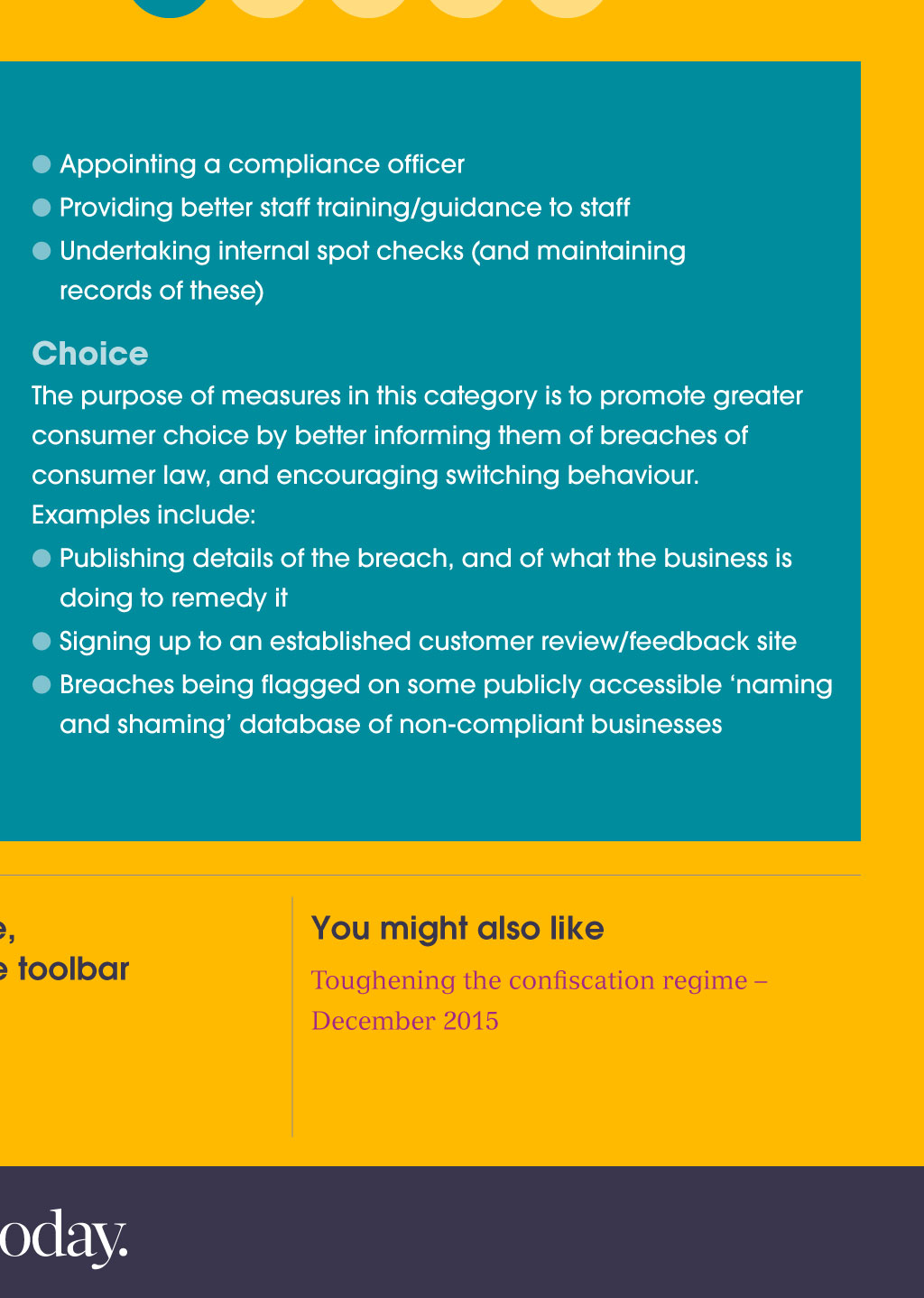

Enhanced consumer measures These measures are designed to give courts and enforcers greater flexibility. Here we explain the purpose of each category. Redress Measures in the redress category are designed to compensate consumers who have suffered loss because of the conduct of a non-compliant business. Where consumers cannot be identified without proportionate cost, ECMs in this category can be made ‘in the collective interests of consumers’ – for example, donation by the business to a consumer charity. Compliance Measures in the compliance category are defined as those intended to prevent, or reduce the risk of occurrence or repetition, of the non-compliant conduct. Examples include: l Collecting – and acting on – customer feedback l Signing up to a primary authority scheme l Appointing a compliance officer l Providing better staff training/guidance to staff l Undertaking internal spot checks (and maintaining records of these) Choice The purpose of measures in this category is to promote greater consumer choice by better informing them of breaches of consumer law, and encouraging switching behaviour. Examples include: l Publishing details of the breach, and of what the business is doing to remedy it l Signing up to an established customer review/feedback site l Breaches being flagged on some publicly accessible ‘naming and shaming’ database of non-compliant businesses Credits Anna Medvinskaia is a barrister at Gough Square Chambers. Images: mania-room / Shutterstock To share this page, click on in the toolbar You might also like Toughening the confiscation regime – December 2015 Legal perspectives In this feature l redress l compliance l choice References 1. Dept for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) consultation on extending the range of remedies available to public enforcers of consumer law, November 2012, page 7 2. For definitions, see ss. 211 and 212. The definition of domestic infringement has been amended by the Consumer Rights Act 2015 (now restricted to such acts or omissions done by those who have a place of business in the UK, or done for those in the UK). The definition of ‘community infringement’ remains unchanged. After much anticipation, enhanced consumer measures (ECMs) were finally made available to enforcers on 1 October 2015. The measures, inserted into the Enterprise Act 2002 by the Consumer Rights Act 2015, expand the consumer enforcement toolkit to include a new set of obligations that can either be agreed with businesses – by way of an undertaking – or imposed by a court, via an enforcement order. The purpose, as stated in the government consultation,1 is to increase business compliance with the law, improve redress for consumers affected by the breach, and create more confident consumers, who will be empowered to exercise greater choice. What are ECMs? Part 8 of the Enterprise Act enables enforcers to prevent conduct that is thought to constitute a domestic or EU community infringement harming the collective interest of consumers.2 This includes most consumer protection measures. In the event of such an infringement, the enforcer must consult with the business and the Competition and Markets Authority to attempt to put an end to the offending behaviour. The Consumer Rights Act 2015 has extended the usual 14-day Expanding the enforcement toolkit Enhanced consumer measures under the Enterprise Act 2002 introduce greater flexibility for enforcers and the courts to apply consumer law. Anna Medvinskaia examines the changes 1 References 3. s. 219A 4. BIS, Enhanced Consumer Measures, Guidance for enforcers of consumer law, May 2015 consultation period to 28 days if certain conditions are met – for example, where the non-compliant business is represented by a body that operates a consumer code approved by certain specified bodies. The enforcer may agree to accept undertakings from the business or, if no such agreement is reached, the enforcer may apply to the court for an interim or full enforcement order. Since 1 October 2015, an undertaking or an enforcement order may include a requirement for the offender to take ECMs. ECMs widen the scope of the measures that an enforcer can expect in negotiations with a business, or apply for in the civil courts. They are designed to give enforcers a degree of flexibility and to achieve better results for consumers. ECMs fall into three categories: (a) Redress (b) Compliance (c) Choice These broad categories are defined in the Enterprise Act 2002,3 although the Act does not include a list of possible measures that would suit each category (see box, ‘Enhanced consumer measures’). The Department for Business, Innovation and Skills’ (BIS’) Guidance for enforcers of consumer law4 offers some assistance, however. The justification for this omission in the legislation is that the enforcer and/or the court are, thereby, given the flexibility to find the most appropriate measure(s) to deal with a non-compliant business. The business is also given the opportunity to put forward proposals that it considers appropriate. Things to consider when using ECMs Timing of the non-compliant conduct It is worth noting that ECMs apply only in relation to conduct that occurs after 1 October 2015 (that is, the start date of s.79 of the Consumer Rights Act 2015). Dialogue in the first instance The BIS guidance outlines the sequence of events that would normally take place: In the first instance, the enforcer should seek to work with the trader that has breached the law to identify suitable measures to deal with the breach. If the trader refuses to cooperate – or disagrees that the measures put forward by the enforcer are just, reasonable and proportionate – the enforcer will have to present their case to the court. It will be for the court to decide, after hearing from both parties, if the measures being proposed by the enforcer – but being rejected by the trader – are just, reasonable and proportionate. A failure to engage with the trader in the first instance could expose the enforcer to abuse-of-process arguments should proceedings later be issued, although these are rarely successful. ECMs as an alternative to criminal prosecution The guidance makes it clear that ECMs would normally be used as an alternative to criminal prosecution, although there may be circumstances in which they could be used alongside a criminal prosecution. The BIS guidance offers the example of a business causing considerable detriment to a number of elderly and/or vulnerable consumers. References 5. s. 219B (1) and (2) of the Enterprise Act 2002 (as amended) 6. Guidance, para. 37 7. 219B (4) Just, reasonable and proportionate ECMs should always be just, reasonable and proportionate.5 When assessing proportionality, the enforcer or the court – as the case may be – will be required to consider, in particular: the likely benefit of the measures to consumers; the costs likely to be incurred by the subject of the enforcement order or undertaking; and the likely cost to consumers of obtaining the benefit of the ECMs. The guidance also clarifies that the enforcer would need to consider whether the use of ECMs would be in the public interest. ECMs cannot be imposed by an enforcer, only by a court It is important to note that a public enforcer cannot impose the measures on a business. What it can do is seek an undertaking from the business that it will put the measures in place.6 ECMs in the redress category Measures in the redress category will only be available when consumers have suffered loss. The guidance makes it clear there is no minimum or maximum amount of loss required before such measures are used, although such considerations may be relevant to questions of proportionality. A further restriction is that the enforcer or the court must be satisfied that the cost of such measures to the business is unlikely to be more than the sum of the losses suffered by consumers, as a result of the conduct that has given rise to the enforcement order or undertaking.7 Importantly, however, References 8. 219B (5) 9. Guidance, para. 40 the cost does not include the administrative costs associated with taking the measures. 8 No financial penalties While the legislation gives significant flexibility to enforcers in relation to ECMs, it is worth remembering that a financial penalty payable to the Treasury cannot be imposed under the measures – although, of course, business can be required to offer monetary redress to consumers. Policing by enforcers There is emphasis in both the government consultation and the BIS guidance on policing of ECMs by the enforcer: ‘The enforcer will need to play a key role in ensuring that the measures are being complied with and, if ordered, consumers are receiving redress.’9 Conclusion The introduction of ECMs is a welcome development, giving enforcers and courts greater flexibility in the enforcement of consumer law. It will be interesting to see to what extent enforcers make use of this greater flexibility, however. Increased pressures on enforcement budgets may prevent ECMs from becoming a go-to option, particularly as enforcers will often be expected to monitor traders’ implementation of such measures.