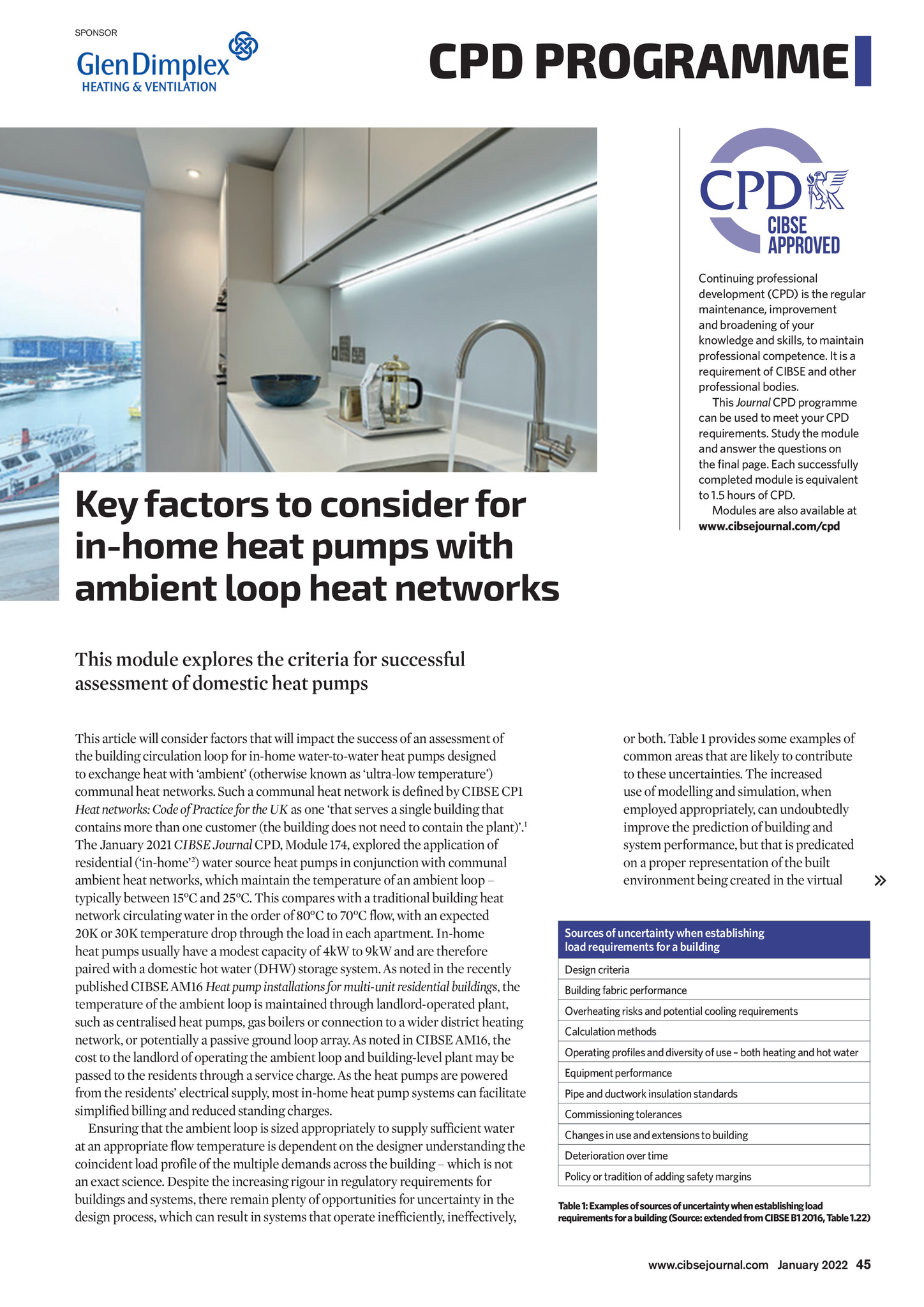

SPONSOR CPD PROGRAMME Continuing professional development (CPD) is the regular maintenance, improvement and broadening of your knowledge and skills, to maintain professional competence. It is a requirement of CIBSE and other professional bodies. This Journal CPD programme can be used to meet your CPD requirements. Study the module and answer the questions on the final page. Each successfully completed module is equivalent to 1.5 hours of CPD. Modules are also available at www.cibsejournal.com/cpd Key factors to consider for in-home heat pumps with ambient loop heat networks This module explores the criteria for successful assessment of domestic heat pumps This article will consider factors that will impact the success of an assessment of the building circulation loop for in-home water-to-water heat pumps designed to exchange heat with ambient (otherwise known as ultra-low temperature) communal heat networks. Such a communal heat network is defined by CIBSE CP1 Heat networks: Code of Practice for the UK as one that serves a single building that contains more than one customer (the building does not need to contain the plant).1 The January 2021 CIBSE Journal CPD, Module 174, explored the application of residential (in-home2) water source heat pumps in conjunction with communal ambient heat networks, which maintain the temperature of an ambient loop typically between 15C and 25C. This compares with a traditional building heat network circulating water in the order of 80C to 70C flow, with an expected 20K or 30K temperature drop through the load in each apartment. In-home heat pumps usually have a modest capacity of 4kW to 9kW and are therefore paired with a domestic hot water (DHW) storage system. As noted in the recently published CIBSE AM16 Heat pump installations for multi-unit residential buildings, the temperature of the ambient loop is maintained through landlord-operated plant, such as centralised heat pumps, gas boilers or connection to a wider district heating network, or potentially a passive ground loop array. As noted in CIBSE AM16, the cost to the landlord of operating the ambient loop and building-level plant may be passed to the residents through a service charge. As the heat pumps are powered from the residents electrical supply, most in-home heat pump systems can facilitate simplified billing and reduced standing charges. Ensuring that the ambient loop is sized appropriately to supply sufficient water at an appropriate flow temperature is dependent on the designer understanding the coincident load profile of the multiple demands across the building which is not an exact science. Despite the increasing rigour in regulatory requirements for buildings and systems, there remain plenty of opportunities for uncertainty in the design process, which can result in systems that operate inefficiently, ineffectively, or both. Table 1 provides some examples of common areas that are likely to contribute to these uncertainties. The increased use of modelling and simulation, when employed appropriately, can undoubtedly improve the prediction of building and system performance, but that is predicated on a proper representation of the built environment being created in the virtual Sources of uncertainty when establishing load requirements for a building Design criteria Building fabric performance Overheating risks and potential cooling requirements Calculation methods Operating profiles and diversity of use both heating and hot water Equipment performance Pipe and ductwork insulation standards Commissioning tolerances Changes in use and extensions to building Deterioration over time Policy or tradition of adding safety margins Table 1: Examples of sources of uncertainty when establishing load requirements for a building (Source: extended from CIBSE B1 2016, Table 1.22) www.cibsejournal.com January 2022 45 CIBSE Jan 22 pp45-48 CPD 190.indd 45 23/12/2021 14:08