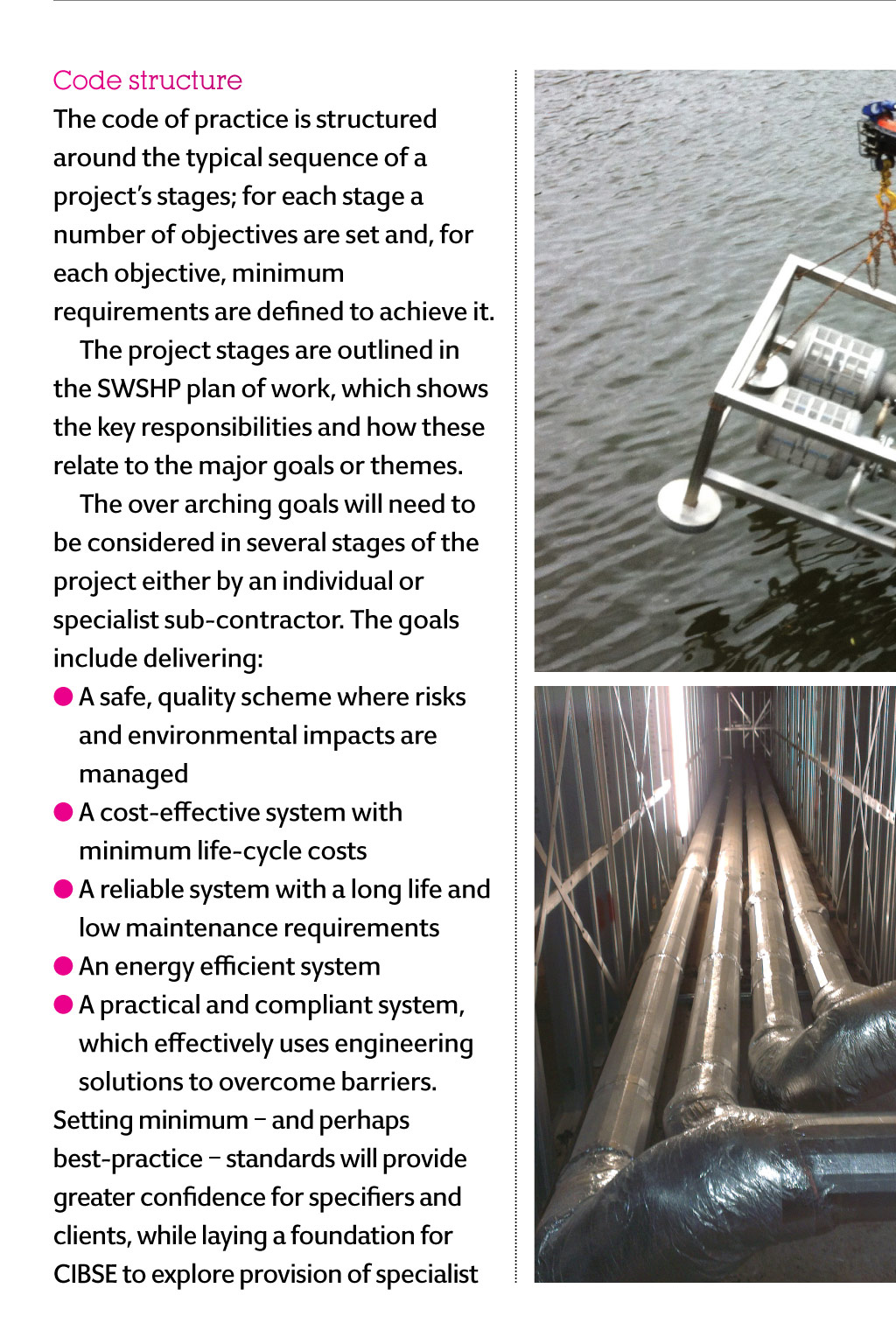

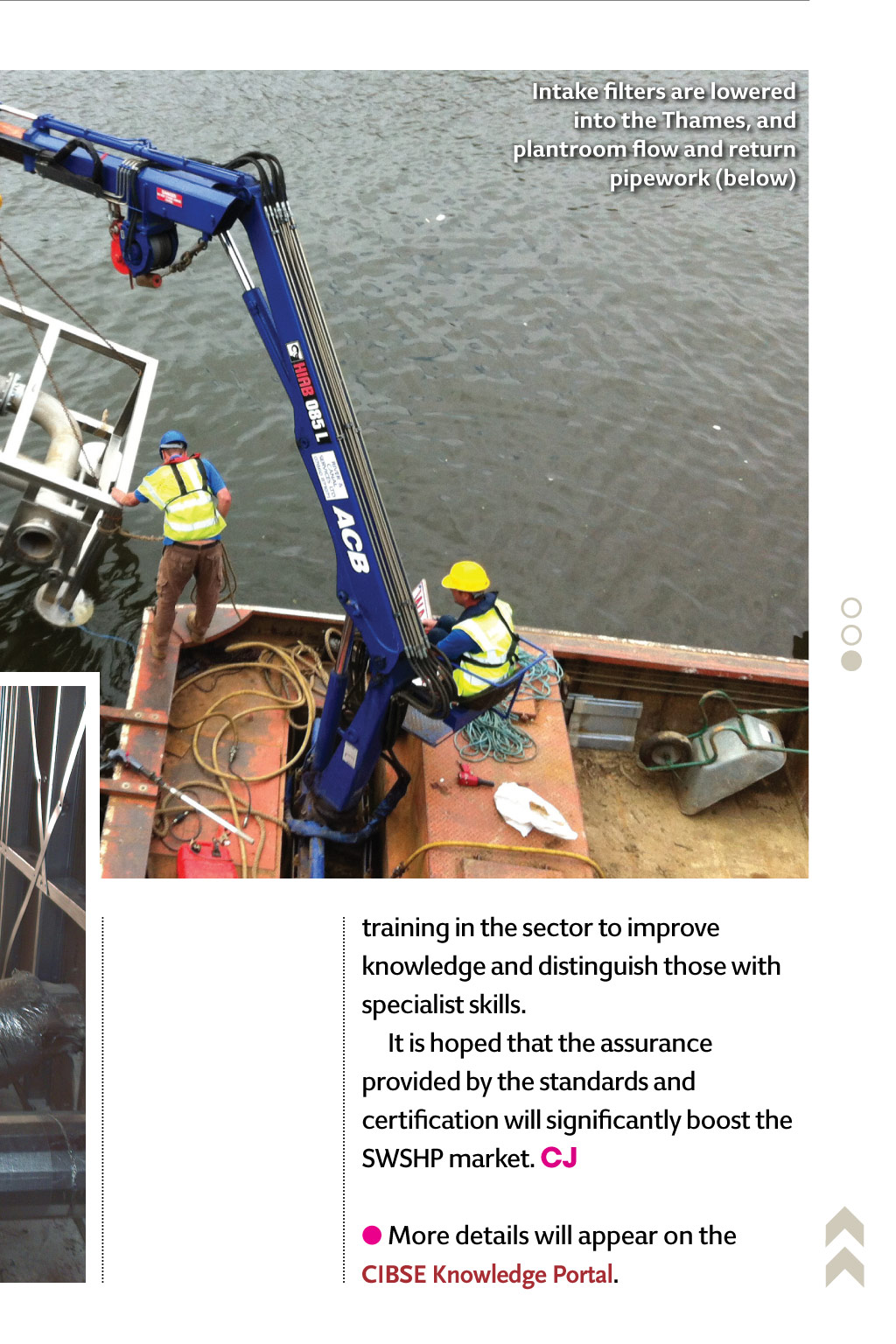

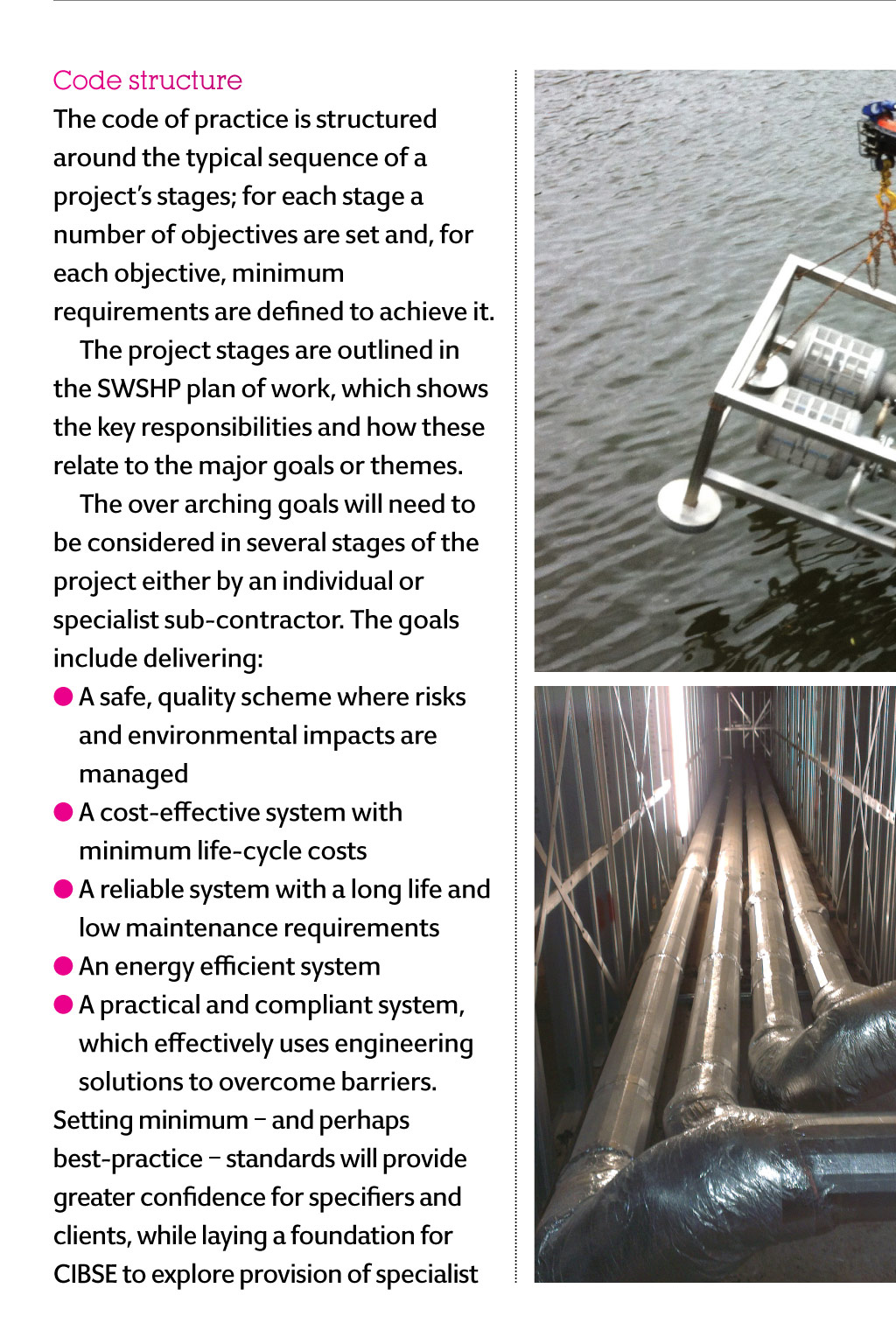

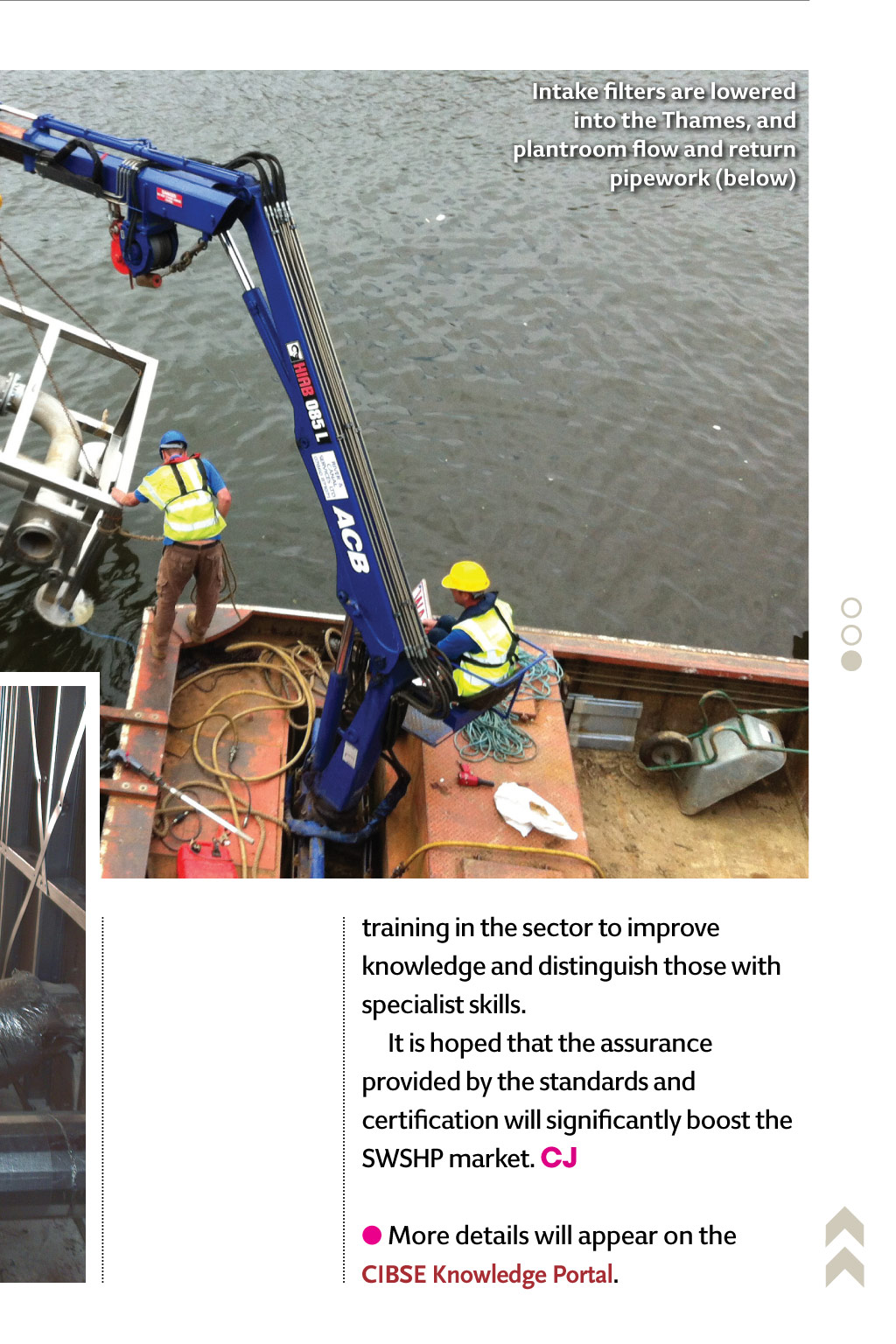

HEAT PUMPS CodE of PrACTICE CoMing on strEAm A surface water source heat pump (SWSHP) system at the 70m Kingston Heights development in London was one of the first of its kind to be installed in the UK. It harvests naturally stored energy from the River Thames and helps delivers underfloor heating and hot water for 56 affordable homes, 81 private apartments and a hotel. This scheme was an exemplar for low-cost renewable energy in the UK, potentially offering a coefficient of performance approaching double figures. Secretary of State for Energy and Climate Change Ed Davey, whose constituency borders Kingston Heights, is a big fan, and has been promoting the technology since its completion. His department has produced a water source heat map of about 40 urban rivers with the greatest potential for SWSHP (more here). There is now a significant impetus for surface water source heat pumps to become a big part of the UKs future energy strategy and this will be spurred on by a SWSHP code of practice. Surface water source heat pumps: A Code of Practice for the UK the draft Code structure The code of practice is structured around the typical sequence of a projects stages; for each stage a number of objectives are set and, for each objective, minimum requirements are defined to achieve it. The project stages are outlined in the SWSHP plan of work, which shows the key responsibilities and how these relate to the major goals or themes. The over arching goals will need to be considered in several stages of the project either by an individual or specialist sub-contractor. The goals include delivering: A safe, quality scheme where risks and environmental impacts are managed A cost-effective system with minimum life-cycle costs A reliable system with a long life and low maintenance requirements An energy efficient system A practical and compliant system, which effectively uses engineering solutions to overcome barriers. Setting minimum and perhaps best-practice standards will provide greater confidence for specifiers and clients, while laying a foundation for CIBSE to explore provision of specialist To boost the uptake of a technology with the potential to tap into plentiful energy stored in rivers, canals, and lakes, a set of new standards are being drawn up by CIBSE and two other industry associations. Liza Young looks at what the Surface Water Source Heat Pump Code of Practice hopes to achieve of which is due to be issued for industry-wide consultation in June is a joint project between the Heat Pump Association, Ground Source Heat Pump Association and CIBSE, supported by the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC). The code of practice will identify and evaluate the options available to extract heat from or reject heat into an open body of water. It will not focus on ground water, such as aquifers, mines, or caverns. Raising standards The purpose of the code is to provide developers and designers with the information they need to consider whether SWSHPs can be used to provide heat on a large scale in densely populated urban areas. The UK has an abundance of viable water resources even in winter and, with SWSHP systems capable of reaching temperatures of more than 80oC, there is value in this technique for designers if the network is well designed and controlled. The code of practice aims to raise standards in the design, implementation and operation of water source heat pumps, and will Without standards and certification, anyone can ignore current guidance and design, install, and operate in any way they like cover the entire project life-cycle. It is anticipated that the code would be used in tendering and specification to ensure contractors and their contracts meet a minimum standard. The adoption of a code by developers could give confidence to customers and property purchasers that the SWSHP has followed a set of design, installation and commissioning standards. In the longer term, following the code could be a condition for receiving planning, private investment or public funding. Once the code is complete, there is potential for developing training and certification to recognise suitably competent engineers in this area. This could lead to registration of SWSHP engineers in a similar way to EPC and DEC assessors. Developers and clients could then select trained specialists who understand how to meet the standards and implement them. Intake filters are lowered into the Thames, and plantroom flow and return pipework (below) training in the sector to improve knowledge and distinguish those with specialist skills. It is hoped that the assurance provided by the standards and certification will significantly boost the SWSHP market. CJ More details will appear here.