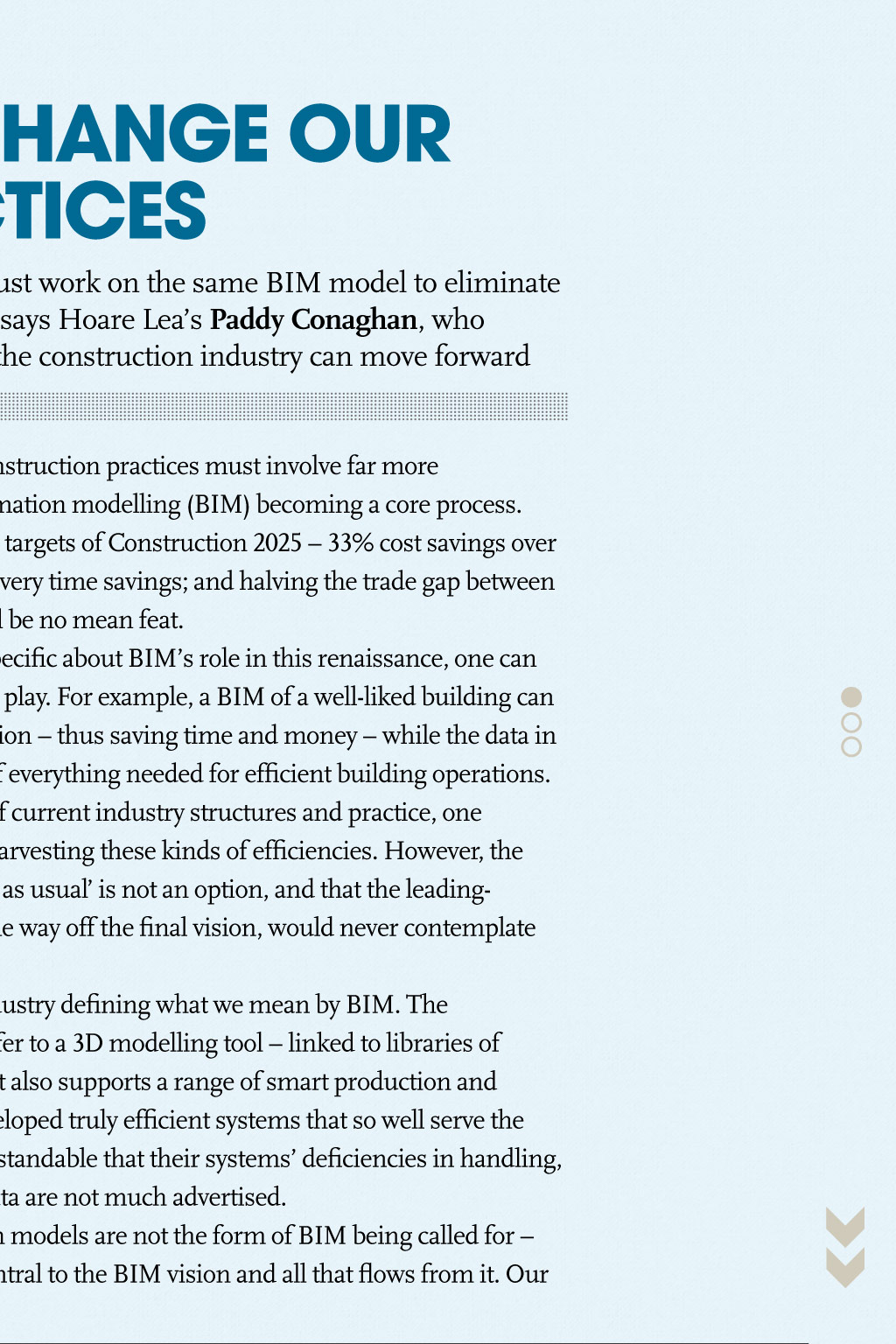

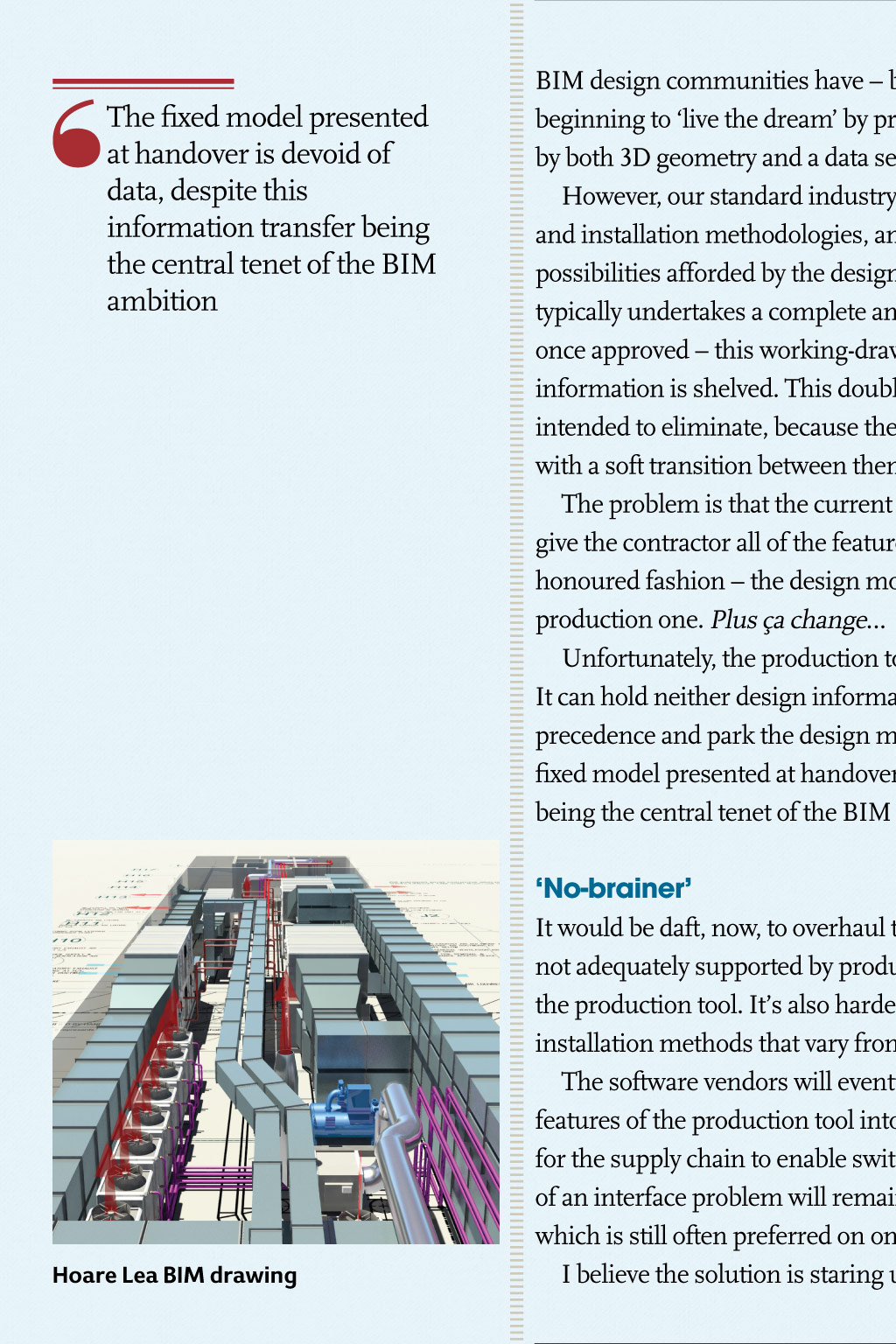

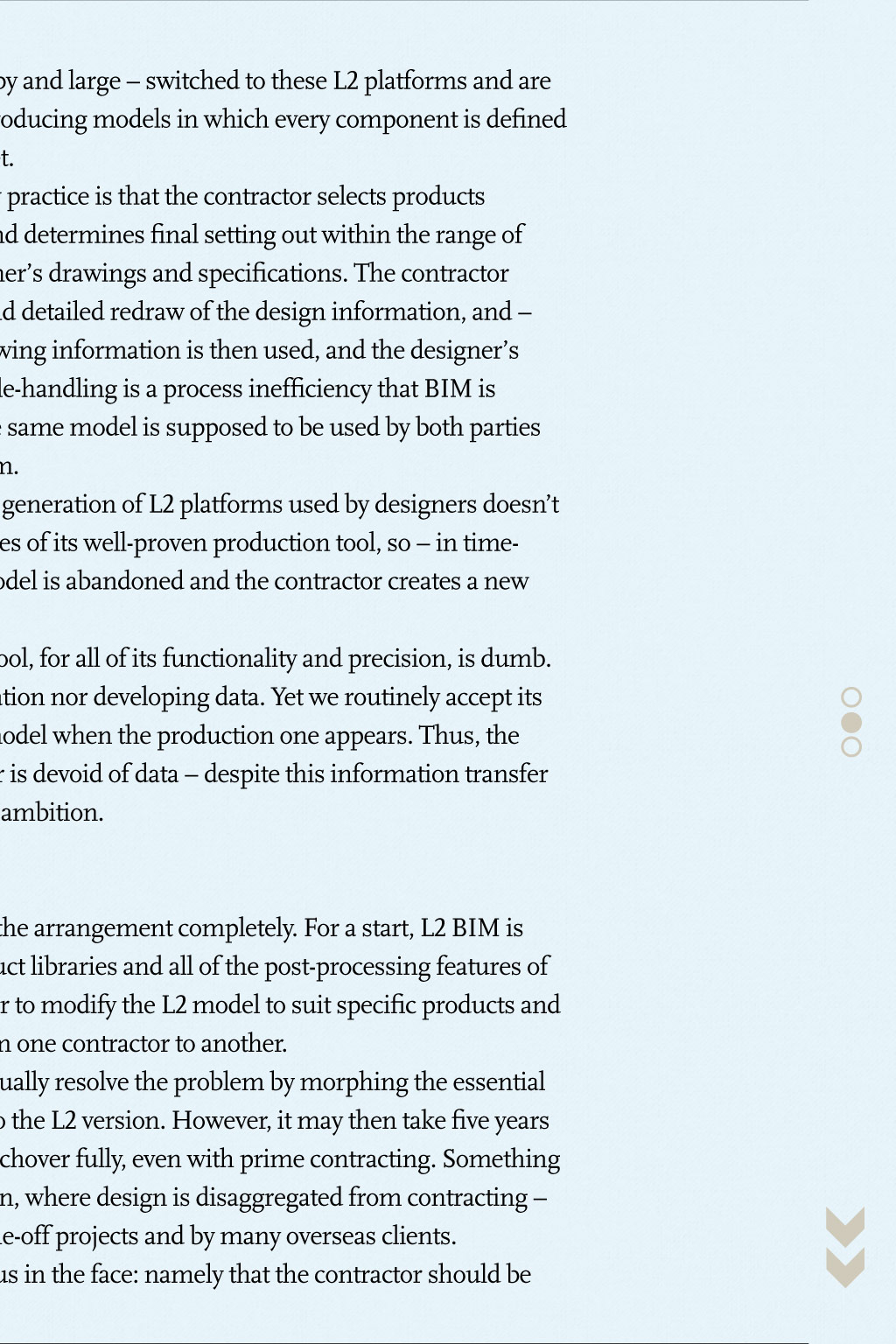

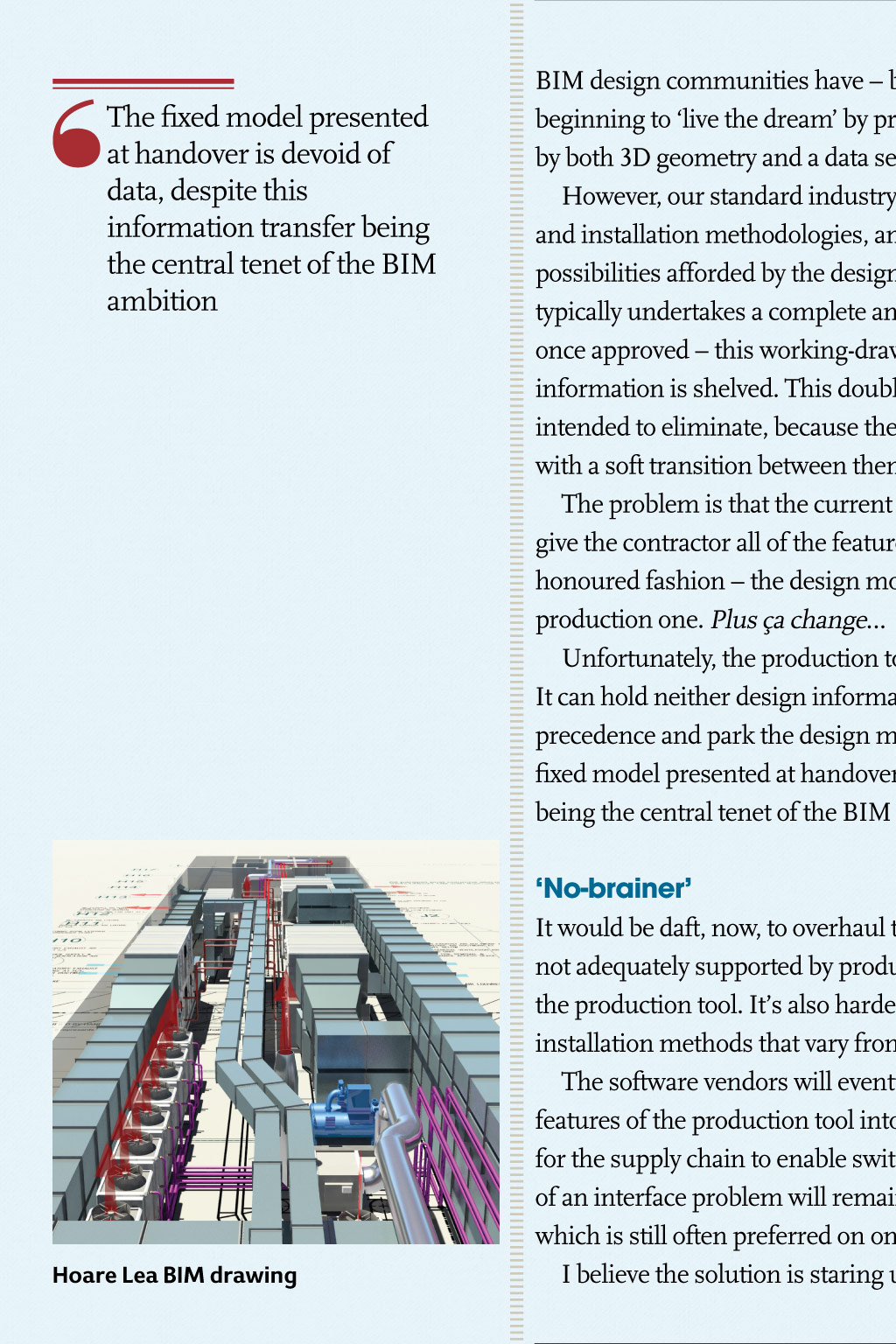

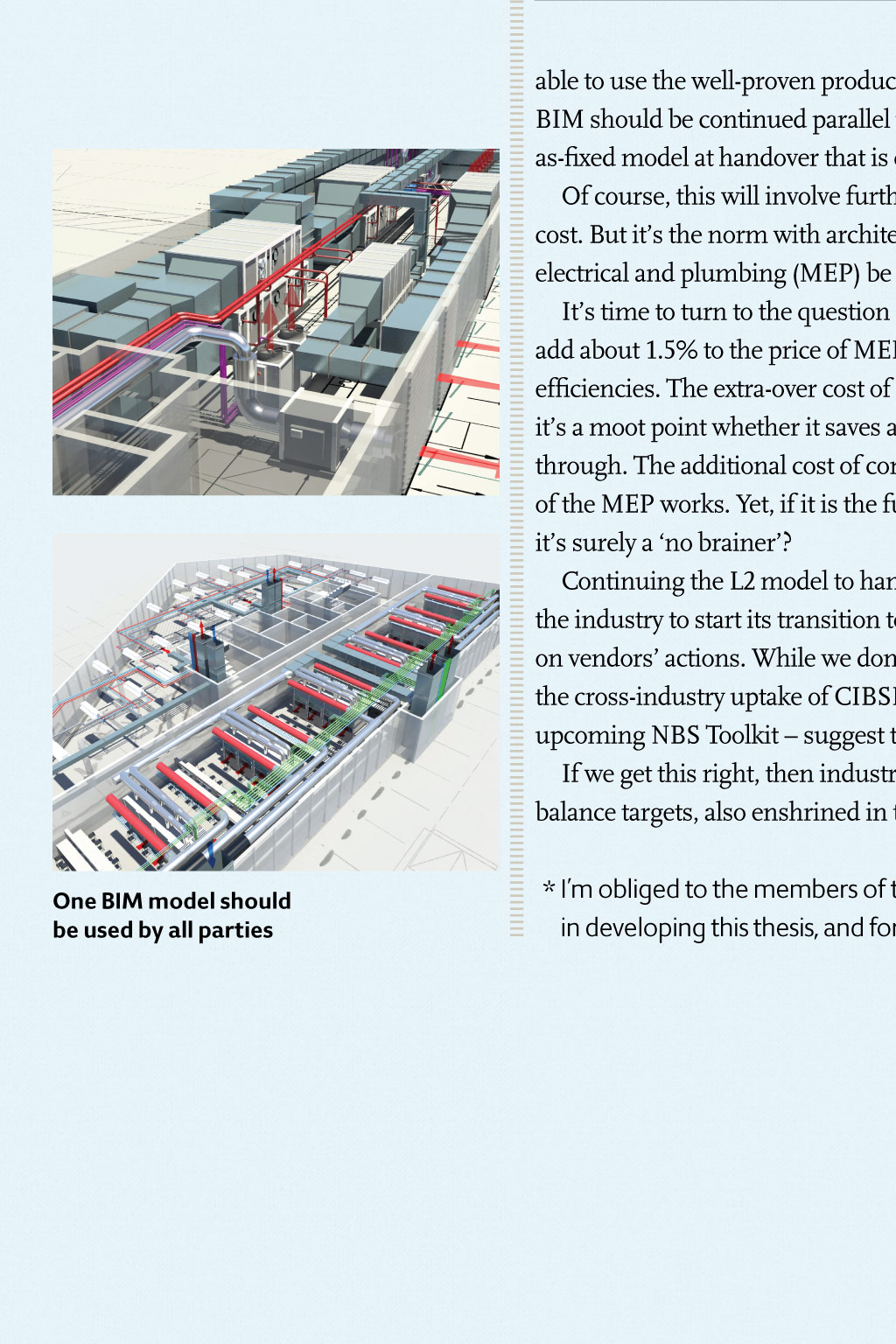

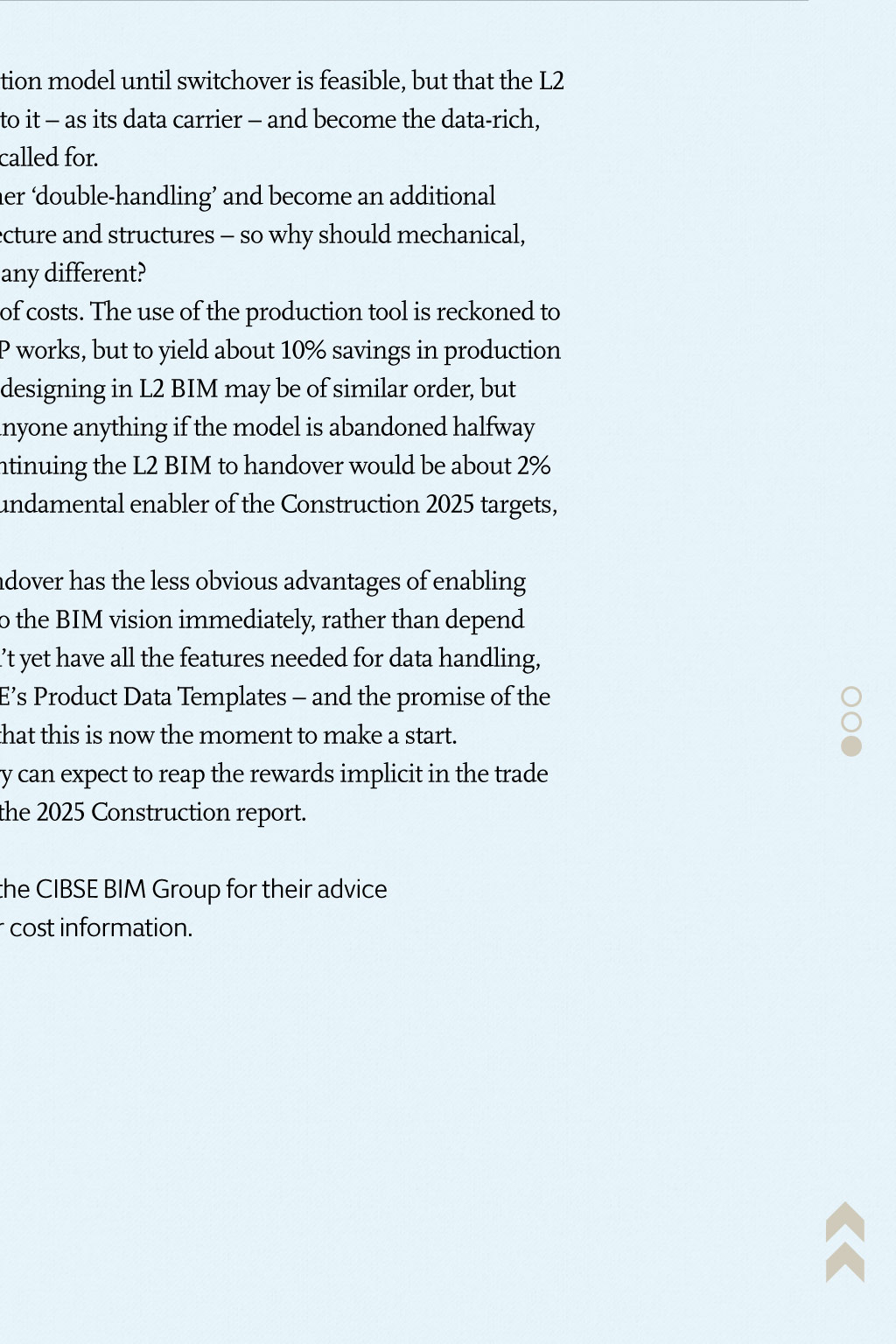

Opinion: Conaghan: Time To Change Our Bim Practices Contractors and designers must work on the same BIM model to eliminate inefficient double-handling, says Hoare Leas Paddy Conaghan, who argues that it is the only way the construction industry can move forward Paddy Conaghan FCIBSE is a consultant at Hoare Lea Web: www.hoarelea.com The fixed model presented at handover is devoid of data, despite this information transfer being the central tenet of the BIM ambition Hoare Lea BIM drawing We are constantly told that UK construction practices must involve far more collaboration, with building information modelling (BIM) becoming a core process. Certainly, achieving the ambitious targets of Construction 2025 33% cost savings over a built assets life; 50% project delivery time savings; and halving the trade gap between product imports and exports will be no mean feat. While the report is not overly specific about BIMs role in this renaissance, one can infer at least some of the factors at play. For example, a BIM of a well-liked building can be reused in briefing the next version thus saving time and money while the data in a BIM provides a full dashboard of everything needed for efficient building operations. True, viewed through the lens of current industry structures and practice, one can equally see many barriers to harvesting these kinds of efficiencies. However, the inescapable truth is that business as usual is not an option, and that the leadingedge BIM users, even though some way off the final vision, would never contemplate reverting to the old ways. We get into a muddle in our industry defining what we mean by BIM. The major trade contractors usually refer to a 3D modelling tool linked to libraries of geometrically exact products that also supports a range of smart production and back-office functions. Having developed truly efficient systems that so well serve the contractors own needs, its understandable that their systems deficiencies in handling, using and reproducing product data are not much advertised. Unfortunately, these production models are not the form of BIM being called for the so-called Level 2 (L2) that is central to the BIM vision and all that flows from it. Our BIM design communities have by and large switched to these L2 platforms and are beginning to live the dream by producing models in which every component is defined by both 3D geometry and a data set. However, our standard industry practice is that the contractor selects products and installation methodologies, and determines final setting out within the range of possibilities afforded by the designers drawings and specifications. The contractor typically undertakes a complete and detailed redraw of the design information, and once approved this working-drawing information is then used, and the designers information is shelved. This double-handling is a process inefficiency that BIM is intended to eliminate, because the same model is supposed to be used by both parties with a soft transition between them. The problem is that the current generation of L2 platforms used by designers doesnt give the contractor all of the features of its well-proven production tool, so in timehonoured fashion the design model is abandoned and the contractor creates a new production one. Plus a change Unfortunately, the production tool, for all of its functionality and precision, is dumb. It can hold neither design information nor developing data. Yet we routinely accept its precedence and park the design model when the production one appears. Thus, the fixed model presented at handover is devoid of data despite this information transfer being the central tenet of the BIM ambition. no-brainer It would be daft, now, to overhaul the arrangement completely. For a start, L2 BIM is not adequately supported by product libraries and all of the post-processing features of the production tool. Its also harder to modify the L2 model to suit specific products and installation methods that vary from one contractor to another. The software vendors will eventually resolve the problem by morphing the essential features of the production tool into the L2 version. However, it may then take five years for the supply chain to enable switchover fully, even with prime contracting. Something of an interface problem will remain, where design is disaggregated from contracting which is still often preferred on one-off projects and by many overseas clients. I believe the solution is staring us in the face: namely that the contractor should be able to use the well-proven production model until switchover is feasible, but that the L2 BIM should be continued parallel to it as its data carrier and become the data-rich, as-fixed model at handover that is called for. Of course, this will involve further double-handling and become an additional cost. But its the norm with architecture and structures so why should mechanical, electrical and plumbing (MEP) be any different? Its time to turn to the question of costs. The use of the production tool is reckoned to add about 1.5% to the price of MEP works, but to yield about 10% savings in production efficiencies. The extra-over cost of designing in L2 BIM may be of similar order, but its a moot point whether it saves anyone anything if the model is abandoned halfway through. The additional cost of continuing the L2 BIM to handover would be about 2% of the MEP works. Yet, if it is the fundamental enabler of the Construction 2025 targets, its surely a no brainer? Continuing the L2 model to handover has the less obvious advantages of enabling the industry to start its transition to the BIM vision immediately, rather than depend on vendors actions. While we dont yet have all the features needed for data handling, the cross-industry uptake of CIBSEs Product Data Templates and the promise of the upcoming NBS Toolkit suggest that this is now the moment to make a start. If we get this right, then industry can expect to reap the rewards implicit in the trade balance targets, also enshrined in the 2025 Construction report. One BIM model should be used by all parties * Im obliged to the members of the CIBSE BIM Group for their advice in developing this thesis, and for cost information.