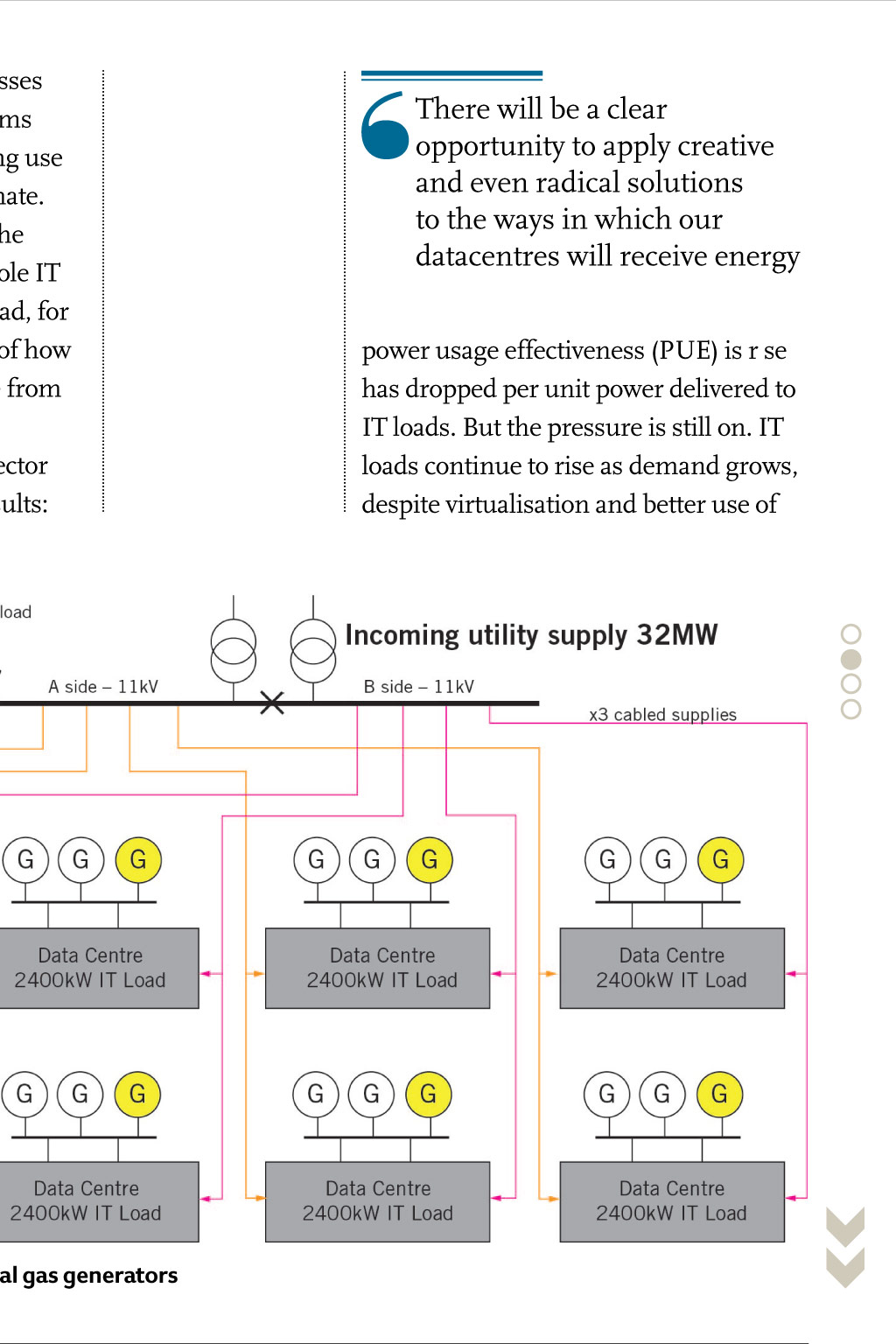

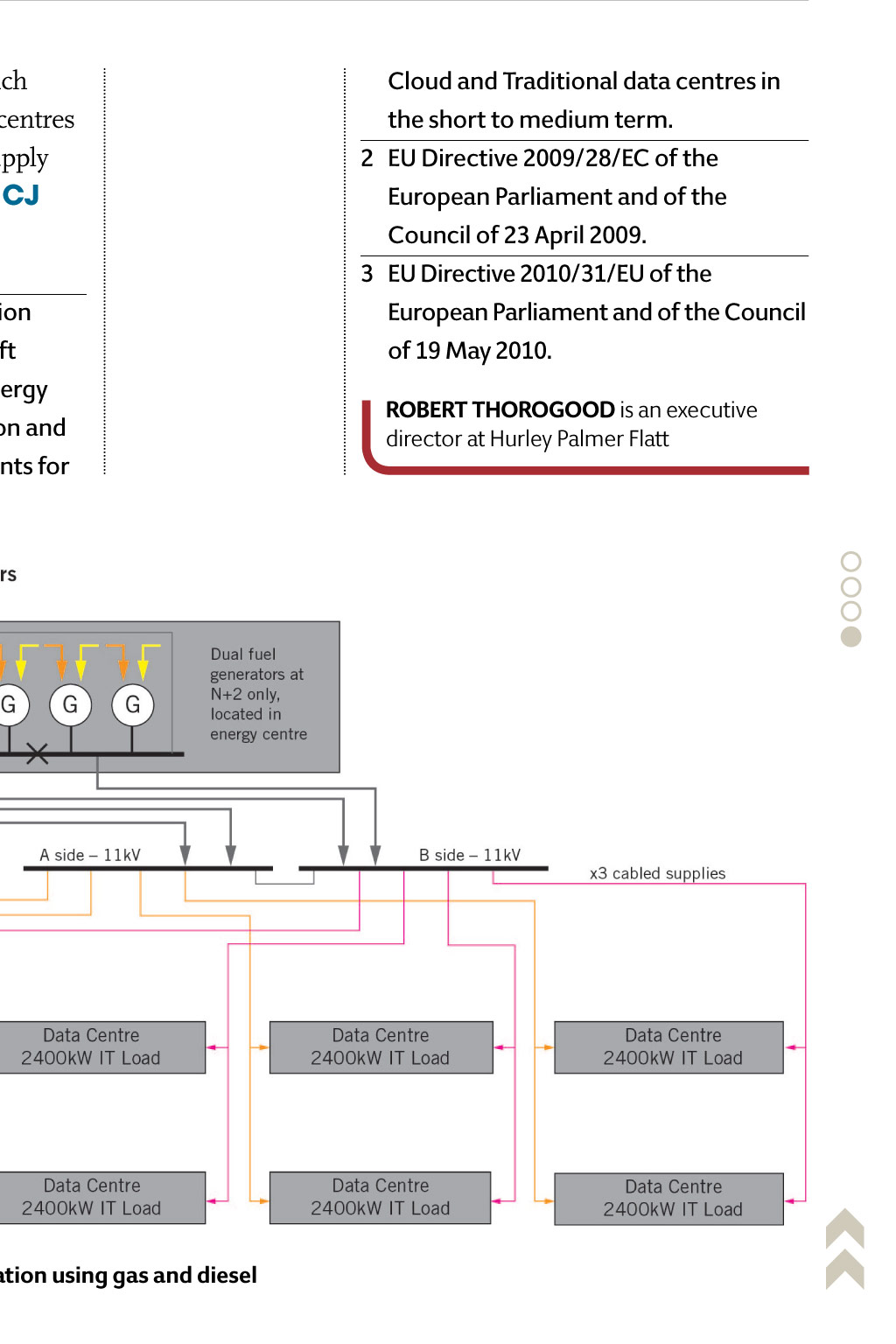

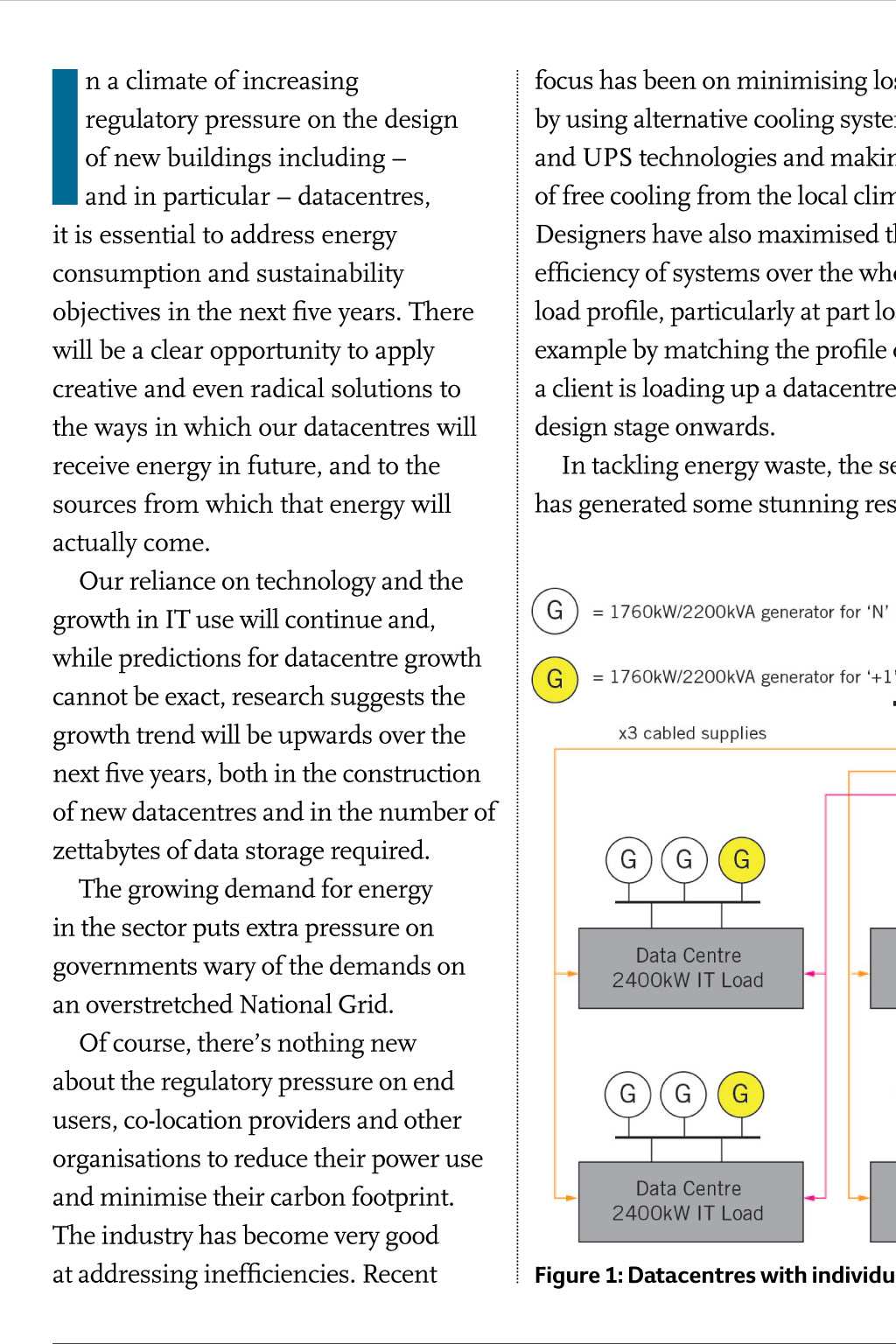

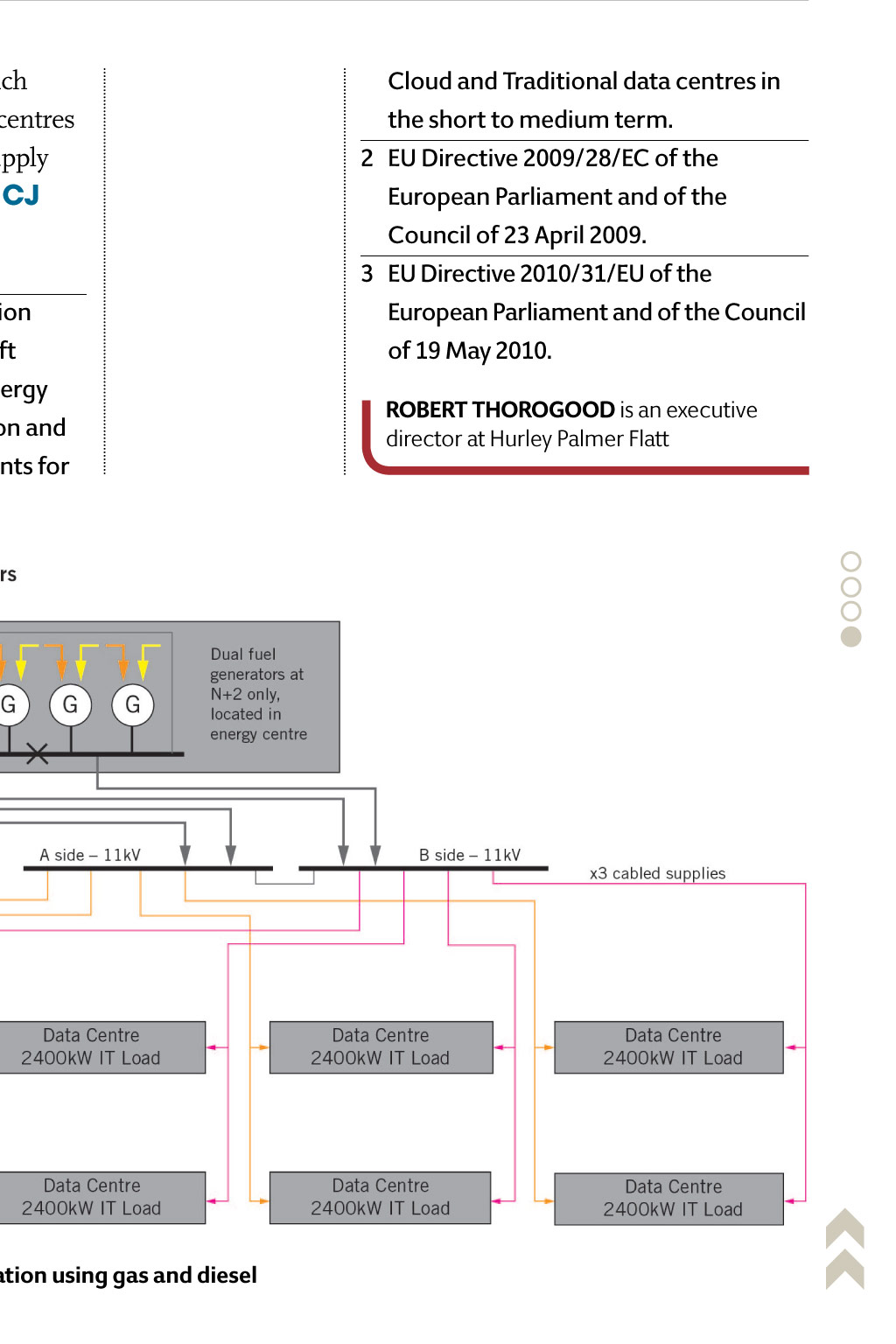

Datacentres Energy Supply Power Complex With Datacentres becoming more energy efficient, the focus is now on decarbonising the energy supply. Hurley Palmer Flatts Robert Thorogood looks at the alternatives I n a climate of increasing regulatory pressure on the design of new buildings including and in particular datacentres, it is essential to address energy consumption and sustainability objectives in the next five years. There will be a clear opportunity to apply creative and even radical solutions to the ways in which our datacentres will receive energy in future, and to the sources from which that energy will actually come. Our reliance on technology and the growth in IT use will continue and, while predictions for datacentre growth cannot be exact, research suggests the growth trend will be upwards over the next five years, both in the construction of new datacentres and in the number of zettabytes of data storage required. The growing demand for energy in the sector puts extra pressure on governments wary of the demands on an overstretched National Grid. Of course, theres nothing new about the regulatory pressure on end users, co-location providers and other organisations to reduce their power use and minimise their carbon footprint. The industry has become very good at addressing inefficiencies. Recent focus has been on minimising losses by using alternative cooling systems and UPS technologies and making use of free cooling from the local climate. Designers have also maximised the efficiency of systems over the whole IT load profile, particularly at part load, for example by matching the profile of how a client is loading up a datacentre from design stage onwards. In tackling energy waste, the sector has generated some stunning results: datacentres from an IT perspective for example where the same server is used to run multiple applications at the same time, such as an email server that is also used to process web hosting The fundamental IT load is not going to disappear with increasingly efficient datacentres, even if a PUE of 1.0 were achieved. Even taking into account the new methods of calculating PUE, the power or energy to feed the IT load still needs to be provided. The new PUE calculation is now significantly different. Crucially the current definition from the Green Grid, the industry-wide organisation set up to provide the metrics for improving resource efficiency, recognises the use of diverse energy sources on a datacentre site, and not solely electricity. This new calculation increasingly opens up more possibilities for using alternative energy sources, such as natural gas or hydro. The latest volley of energy directives indicate that action needs to be taken soon to address energy use and sustainability. The EUs 2020 targets for the UKs share of energy drawn from renewable sources in gross final consumption should see a rise from 1.3% in 2005 to 15% by 2020. EU Member States are also subject to Article 9 an energy performance directive that all new buildings must be almost zero carbon by 2020. The implications of this are that the technical, environmental and economic feasibility of high-efficiency alternative energy systems will need to be taken into account before construction begins on a datacentre or other development. These may include: l Decentralised energy supply systems based on energy from renewable sources l Co-generation (far from ideal because the provision of heat is of no use to a datacentre, unlike a hospital or office) l District or block heating or cooling, particularly where it is based entirely or partially on energy from renewable sources l Heat pumps. While the best solution will always be specific to user requirements and location, the rule of thumb is that energy required should be generated locally or on site, avoiding potential loss of energy through grid distribution. One recent high profile example of this is Googles 10-year power purchase agreement to acquire the electricity output of a Swedish wind farm. The energy will power its datacentre at Hamina in Finland, and is the second such agreement brokered by the tech giant. Energy/fuel options might also include other non-combustion sources, such as photovoltaics or tidal; combustion sources including natural gas or methane, diesel, biodiesel, and biomass fuel; and alternative fuel sources such as methane produced from anaerobic digesters, or hydrogen produced from biomass gasification. The size of datacentres is increasing. Typically, over the last few years, IT loads of between 5MW and 20MW have been common but, with scaling using modular build-outs, sites with IT loads of 25MW to 100MW are now being planned or proposed. The question to consider is whether current principle designs scale up to these larger build-outs? I would ask whether we need to think radically about how power is provided to a site, recognising also the preference, if not requirement (as it will be in the EU) from 2019, to have new-build sites that are carbon neutral. towards the standard ways in which energy/power is provided to datacentres in Europe, and the solutions we apply will also have to change radically. cJ Cloud and Traditional data centres in The latest volley of energy directives indicate that action needs to be taken soon to address energy use and sustainability power usage effectiveness (PUE) is r se has dropped per unit power delivered to IT loads. But the pressure is still on. IT loads continue to rise as demand grows, despite virtualisation and better use of Figure 1: Datacentres with individual gas generators dual fuel solution One extremely radical solution to the short to medium term. 2 EU Directive 2009/28/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009. REFERENCES: 1 Researches drawn from Dominion Virginia Power, Belady/Microsoft the challenge of creating a new build carbon neutral datacentre could focus on changing the way in which the infrastructure to a facility is formed. This might involve centralising and combining the standby generation by using dual fuel engines in this case gas and diesel (Figure 2). Contrast this with Figure 1, which shows a build-out of multiple datacentres, each with their own more conventional IT load, UPS, cooling and generator plant. The benefits of the dual-fuel solution is that the requirement for a large say 132kV utility connection, something which takes years to provide and plan, can be completely dispensed with. Power generation using this onsite dual-fuel gas and diesel solution de-risks from the electricity grid (and the gas grid is much more robust). It is certainly food for thought, but one thing is certain the next five years we will see a major change in attitudes There will be a clear opportunity to apply creative and even radical solutions to the ways in which our datacentres will receive energy and Cisco predict increasing energy demand, increasing construction and increasing zettabyte requirements for Figure 2: Centralised power generation using gas and diesel 3 EU Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 May 2010. ROBERT THOROGOOD is an executive director at Hurley Palmer Flatt