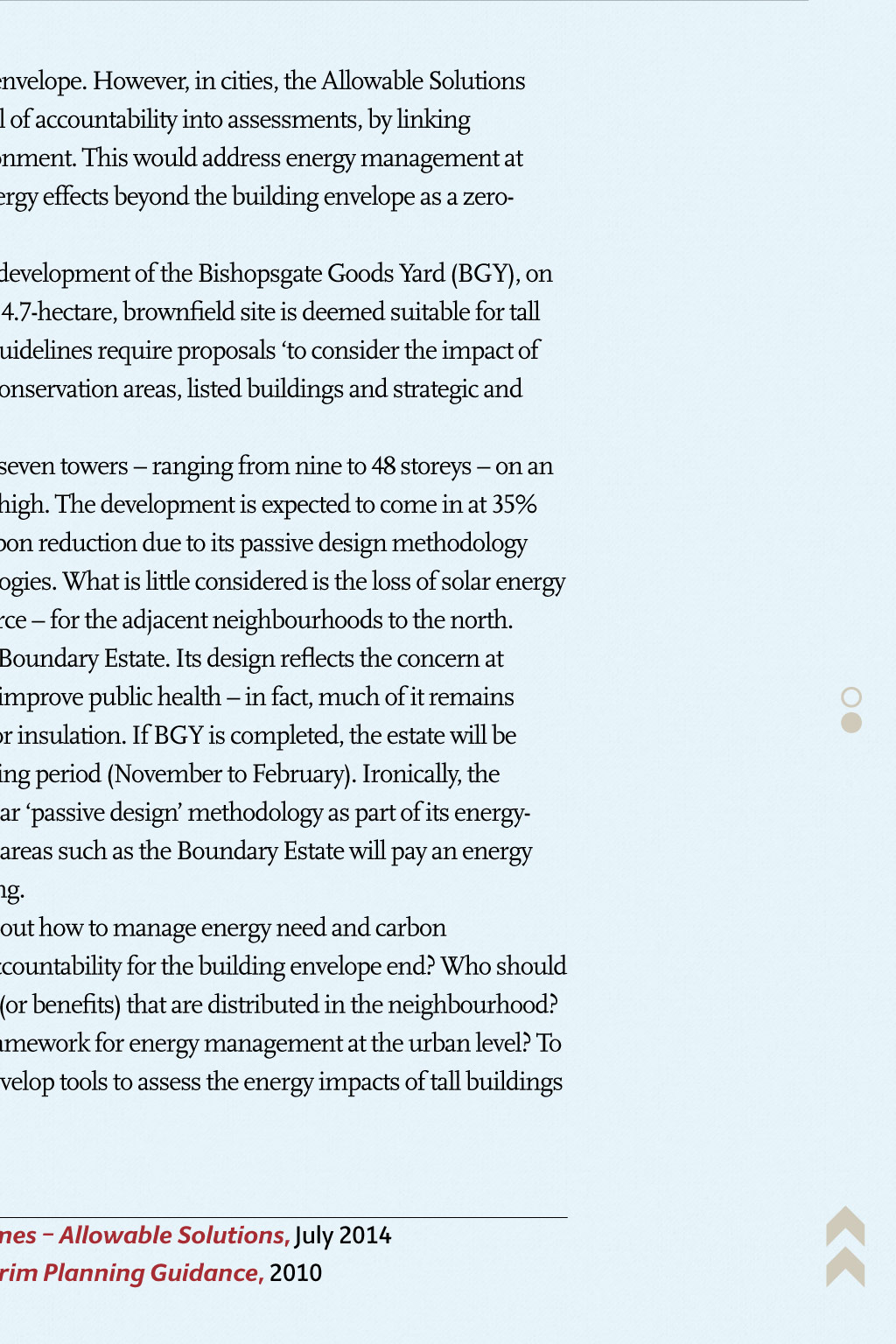

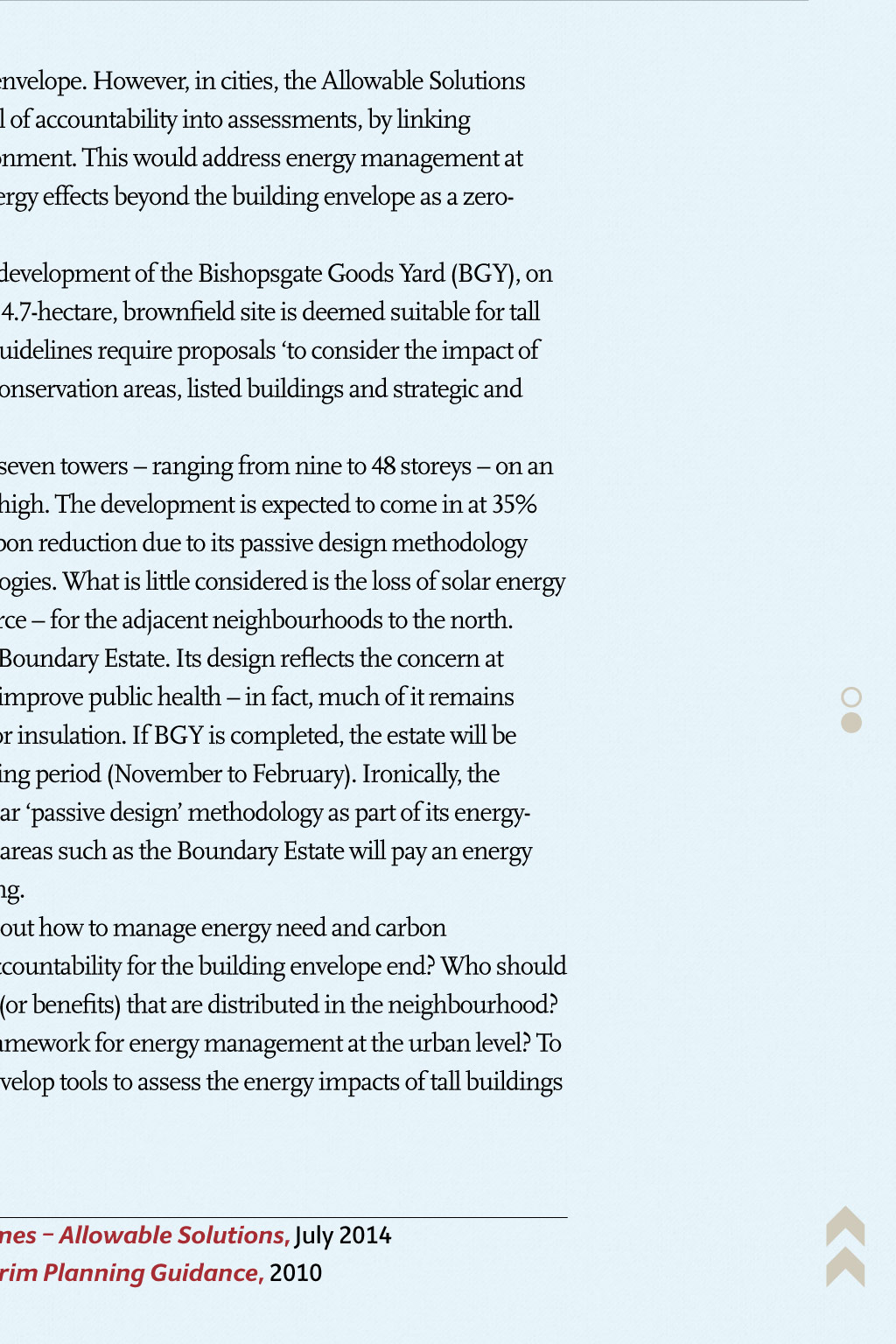

Opinion: Pushing The Envelope The environmental impact of new buildings on neighbours should be taken into account when calculating energy use. Julie Futcher and Gerald Mills says Allowable Solutions offers an answer Julie Futcher is an architect at Urban Generation, Gerald Mills is an urban climatologist and lecturer at University College Dublin email: Julie@climate22.com twitter: @juliefutcher As the Bishopsgate development stands, areas such as the Boundary Estate will pay an energy price for a carboncompliant building Click/tap here to enlarge image The proposed BGY scheme will have a detrimental effect on the Boundary Estates ability to benefit from solar gain of nearby areas The London skyline is changing rapidly, as tall and very tall buildings are inserted into a low-rise urban setting. Although many of these buildings have impressive energy credentials their impact on their surroundings is not accounted for. The best-known example is 20 Fenchurch Street, which casts a shadow over buildings to its north and, for a brief period, directed sunlight onto an adjacent street to its south, melting cars. The Heron Tower has embedded PVs in its south-facing faade, and has organised its indoor space to avail itself of this renewable energy source. However, it does not have a right to this resource, and will lose it as soon as 100 Bishopsgate is completed, casting Heron Tower in its shadow. Buildings in cities are not energy islands; they share the space and passive and renewable resources with other buildings and outdoor areas. Energy-management strategies require a spatial approach that accounts for the wider impact of buildings on their surroundings. Here, we consider Allowable Solutions under the framework of zero-carbon buildings as a means of addressing accountability. Current strategies towards zero carbon buildings are founded on two principles: the inherent efficiency of the building fabric and energy-demanding systems (the regulated loads); and the supply of energy from renewables. Both are onsite mitigation measures to meet carbon compliance, but may not be enough to achieve zero carbon under the 2016 Building Regulations. This is especially the case in cities where passive-resource opportunities are degraded and onsite renewables are limited. To address this shortfall, a third principle will be introduced permiting buildings to mitigate the remaining onsite emissions through offsite actions (Allowable Solutions) that have yet to be defined1. Currently, buildings are considered as stand-alone entities for which energy management ends at the building envelope. However, in cities, the Allowable Solutions policy could introduce a higher level of accountability into assessments, by linking buildings to their immediate environment. This would address energy management at an urban scale, by including net energy effects beyond the building envelope as a zerocarbon objective. A good example is the proposed development of the Bishopsgate Goods Yard (BGY), on the edge of the City of London. The 4.7-hectare, brownfield site is deemed suitable for tall buildings, for which the planning guidelines require proposals to consider the impact of both taller and lower buildings on conservation areas, listed buildings and strategic and local views.2 The current BGY proposal is for seven towers ranging from nine to 48 storeys on an existing podium around 15 metres high. The development is expected to come in at 35% under Part L (2010), with a 17% carbon reduction due to its passive design methodology and the use of low and zero technologies. What is little considered is the loss of solar energy both as a passive and active resource for the adjacent neighbourhoods to the north. Among these is the 125-year-old Boundary Estate. Its design reflects the concern at the time for ventilation and light to improve public health in fact, much of it remains as built, with single glazing and poor insulation. If BGY is completed, the estate will be shaded for much of the winter heating period (November to February). Ironically, the BGY development proposes a similar passive design methodology as part of its energymanagement strategy. As it stands, areas such as the Boundary Estate will pay an energy price for a carbon-compliant building. This example poses questions about how to manage energy need and carbon compliance in cities. Where does accountability for the building envelope end? Who should be accountable for the energy costs (or benefits) that are distributed in the neighbourhood? Could allowable solutions offer a framework for energy management at the urban level? To answer these questions we must develop tools to assess the energy impacts of tall buildings on their neighbourhood. REfEREncEs: 1 Next steps to zero carbon homes Allowable Solutions, July 2014 2 Bishopsgate Goods Yard: Interim Planning Guidance, 2010